Carl Rakosi Biography

Family Background

Born on November 6, 1903, in Berlin, Germany, Carl Rakosi was the only first-generation American immigrant among the core “Objectivists.”1Basil Bunting was born in Northumberland, England and lived in the United States for short stints at various points, but remained a British citizen until his death.

Parents

Rakosi’s parents, Leopold Rakosi (born Leopold Rozenberg sometime between 1872 and 1873)2Various government documents give different dates. His naturalization record gives his birthday as May 16, 1873, his WWI draft registration card gives his birth as May 13, 1872. and Flora Steiner (born 1879), were Hungarian Jews who had married in Budapest in 1897. Their first son, Lester, was born in 1898, and the family emigrated to Berlin, Germany for business reasons shortly thereafter. At the time of Carl’s birth, Leopold was one of three Hungarian partners in a firm that manufactured canes and walking sticks, making him a respectable member of the Jewish merchant class in Wilhelmine Germany. Rakosi described his father as looking like “an ideal Swede,” with a “trim moustache and grey eyes and straight gentlemanly nose and fair complexion … looks, clothes, manner clean-cut … the voice big and resonant, unexpected in such a small man, and an air of utter integrity.”3”Carl Rakosi” in Contemporary Authors Autobiography Series, Vol. 5, p. 194.

While he was never especially active politically, Leopold had deep emotional sympathies for socialism, which originated during his years working in Germany. According to Carl, while on a lunchtime walk through Berlin’s Großer Tiergarten, his father chanced one day upon a public address being given by prominent German socialists Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg and found himself:

dazzled by the power of the words, moved in every cell by the speaker’s deep moral passion, which he felt at white heat, and his commitment to a cause from which he himself could not benefit, and the realization came to my father then that this was the noblest thing a man could do . . . he could not conceive of anything nobler . . . to have a great cause, to be a spokesman, an advocate, a champion of the oppressed and downtrodden. He never got over that. There was awe in his voice, almost reverence, and a hush, and his face became transformed when he mentioned the names of the speakers, and I, sitting at my favorite spot next to his right elbow by the workbench, basked in the glow of his idealism. And when he went on about the brotherhood of man and the necessity for justice, his favorite themes, a wave of emotion surged through me and lifted me up, and I was glad.4”Carl Rakosi” in Contemporary Authors Autobiography Series, Vol. 5, p. 194.

The first year of Rakosi’s life was a very difficult one for his family. Just as the cane manufacturing firm was beginning to prosper, Leopold’s wealthier partners bought him out of the firm, leaving him without a job. Furthermore, although Rakosi was too young to remember this time clearly, he later suspected that his mother probably experienced severe postpartum depression (then called melancholia), which prevented her from fulfilling the maternal responsibilities expected of her. In later life, Rakosi was unable to recall any precise memories of his mother, and knew only that others described her as very beautiful, with waist-length black hair and dark, expressive eyes.5In a brief autobiographical essay Rakosi related that he did not remember seeing his mother or her ever touching him, even in the 5 years he lived with his grandparents in Baja (Autobiography, 196). Rakosi told Kimberly Bird in 2002:

What I remember … is always being alone. At least that’s the way I remember it. I was really terrified. This is from birth to my first year. Now, whether this is an actual memory or not, I’m not sure, but it feels like a memory of being utterly alone, in a huge room. That has left me with a fear to this day of being alone in a house. This is not a dream; it’s a memory, and I am bonded to it. It’s a memory of no one being there and no one coming. A mother was not there. I’m sure.6”Scenes from My Life” in Collected Prose, 85. In another published autobiographical account of his childhood, he relates a similar memory: “I am in a very long room, so long that I can not see its end. There is very little furniture. The ceiling is very high and vast. There are shadows. The further away they are, the longer and heavier. There is no one there. I lie in my crib. All I’m aware of is that I am. And the silence. The silence is loud. No one comes. The silence is all there is. The nothing is oppressive. Hours go by and it becomes harder and harder to bear. There is no end. There is only the silence. And nothing. But beyond what I can see is something ominous looming (Autobiography, 195).

Whatever the precise cause of the rupture, Leopold and Flora separated in 1904, and divorced soon after. Following their separation, Leopold emigrated to America (via Budapest) while Flora and the two boys returned to her parents’ home in Baja, Hungary, a city of around 25,000 near the Serbian border. Rakosi remembered this time with mixed feelings:

I don’t remember ever seeing my mother, don’t remember her ever touching me or holding me when I was little. My father left her when I was only one year old and my brother Lester and I were brought up for the first six years of my life by her mother in a small town in southern Hungary. My mother lived somewhere in our house but always out of sight and hearing. Not that I felt anything was missing … but it has left a great mystery in my biological past. A big chunk is missing, the part that would have told me who I am biologically. As a consequence, there has been a slight psychic discontinuity, both things which look as if they belong in the making of a poet-self.7Archive for New Poetry, UCSD Mandeville Special Collections, MSS 0355, Box 4, Folder 4.

Maternal Grandparents

While he could recall no interaction with his birth mother, Rakosi had a much happier relationship with his maternal grandparents, Samuel and Rosalia [Róza] Steiner. Rakosi was especially fond of Róza, who he described as being “my mother, but more gentle and kind than a mother.”8”Scenes from My Life” in Collected Prose, 85. He would later recall her with deep love:

The eyes are sad and reflective, the face tired, beginning to show wrinkles, but the mouth smiles and an incomparable sweetness, her character, exudes from her, holding nothing back, and envelops me. She leans towards me, attentive, smiling, and I respond in like, as I had learned to do from her, also smiling, all inside me light. But I can not do her justice.9”Scenes from My Life” in Collected Prose, 85

Rakosi recalled his Steiner grandfather as

a formidable gentleman with a Bavarian-style beard. At this time in his life, he was reduced in circumstances to owning a small umbrella and notions store, where he did his own repairing, but I gather that at one time he had done well in business but had gone broke, trying to help his sons establish themselves. He had to work hard. In my memory of him there was something stern …. despondency probably ….. which I couldn’t understand.10UCSD Special Collections, MSS 0355, Box 4, Folder 6.

The Steiner’s had four children, three sons and a daughter (Carl’s mother, Flora). Their youngest son, Karoly was Carl’s namesake (Karoly is the Hungarian version of the German Karl/Carl) and had died as a young man in a building collapse. Flora’s other two brothers had emigrated to Munich, where they married German women and converted to Catholicism. Rakosi recalled somewhat strained relations within the family, largely the result of economic, cultural and religious disagreements (he would later learn that his grandfather had been essentially bankrupted in trying to help these two uncles, who the rest of the family viewed as dissolute, lazy, and dishonest, establish themselves financially in Germany).

Apart from the total absence of his mother and occasional rock fights between the local Serbian and Hungarian Jewish children in the neighborhood, Rakosi’s other memories of his childhood in Baja were generally idyllic. His grandparents lived in a modest home, with a barn and mulberry trees behind, owned a horse, and kept chicken and geese. At age five, he was enrolled in a local Jewish community school, and he and Lester lived happily with their grandparents in Baja until the following year, when the two boys left to join their father in America.

Paternal Grandparents

Rakosi never met his paternal grandparents (Barbara Mayer and Abraham Rozenberg), Hungarian-speaking Jews native to Szilágy megye (Sălaj county), a mountainous, forested region of Transylvania which became a part of Romania following the signing the Treaty of Versailles. His grandfather made his living as a grain merchant and was a tall man with a long “biblical” beard that marked him as visibly Jewish among their mainly Transylvanian peasant neighbors, who referred to him as “Father Abraham.”11”Carl Rakosi” in Contemporary Authors Autobiography Series, Vol. 5, p. 194.

The Rozenbergs had four children, two boys and two girls, all of whom moved to Budapest as teenagers in search of better educational and vocational opportunities. Their eldest son, Jacob, had been an exceptionally promising student at the Jesuit gymnasium in Szilagymegye, and the teachers there wanted him to continue his studies at the University of Budapest. Because the family both lacked the money to support him as a student and the university had strict quotas on the number of Jews that could be admitted, his Jesuit instructors proposed that the church could pay for his university studies provided that Jacob converted to Catholicism. Jacob and his parents agreed to this arrangement, but Rakosi recalled that his father Leopold:

was deeply disturbed by this because nothing offended his moral sense more than a Jew giving up his religion and identity to become a Christian, especially for practical reasons. He avoided talking about it because he was very fond of his brother and looked up to him.

Jacob graduated with honors from the University and went on to teach philosophy there for many years. What must have been for reasons of expediency he changed his name to Rakosi, a variant of Rakoczy, Hungary’s great national hero. With that, he ended once and for all his connection to the world of Szilagymegye and “Father Abraham.” In Budapest, however, it was not at all unusual for Jews to take on Magyar names, not necessarily because of expediency but because they had become Magyars in spirit and wanted Hungarian names to show it. …

Towards my father he acted as a guardian. Knowing that my father would have to have some kind of a trade to make a living, Jacob arranged a watchmaker apprenticeship for him with a master craftsman in Budapest, a reputable Christian approaching retirement age. My father was only thirteen then. By agreement he was to work and learn under this master for the whole time, a period of seven years. In return he lived in the master’s home, got room and board and pocket money, and agreed to behave decently, according to the life-style in the house. Living there, he came to feel like a member of the family, and the master felt the same towards him and looked out for his welfare.12”Carl Rakosi” in Contemporary Authors Autobiography Series, Vol. 5, p. 194.

Following the completion of his apprenticeship, Leopold served as a hussar (cavalry officer) in the Hungarian army. Just as Jacob had done, Leopold changed his surname to Rakosi upon coming of age in honor of Rákóczi Ferenc [Francis II Rákóczi], a Hungarian folk hero who led an uprising against the Habsburgs in the early eighteenth century. Though he did not follow Jacob in adopting Catholicism, Rakosi described his father during that period of his life a well-integrated patriot who “regarded himself as a Hungarian first and a Jew next.”13Oral History, 28.

LEAVING BAJA, EMIGRATING TO THE UNITED STATES

Following his dismissal from the cane-making partnership in Berlin, and the dissolution of his marriage to Flora, Leopold emigrated to the United States, hopeful that his training as a master craftsman in Europe would provide better economic prospects in an environment with greater demand for skilled workmen. Leopold arrived in the United States in June 1905, settling first in Chicago, where he found work as a jobber, repairing chronometers for Moore and Evans, a large wholesale jewelry firm. In Chicago he also met and married Rose Kulka, a fellow Hungarian whose family came from what is now Slovakia.

In 1910, when Carl was six years old and Lester was eleven, Rose made a solo voyage to Baja to fetch the boys and bring them to live their father in the United States. Neither Carl nor Lester had ever met their step-mother before, and only Lester had any memories of their father, so one can only imagine the feelings that accompanied her arrival and Carl’s separation from the only family he had ever known. Rakosi would later write of this parting from his grandmother:

I can imagine the final moment. The bags are packed. We are all dressed, ready to leave. The time has come. All I am thinking of is the going and the necessity to act as if this were like any other day. She has suppressed her tears so as to make the parting bearable to me. I walk up to her and like my granddaughter Julie, also six at the time I wrote this, let myself be hugged and kissed with that self-possession and vigilance which protect children. And I leave without recognizing her grief or even acknowledging that this is a separation.

Forgive me.14”Scenes from My Life” in Collected Prose, 85-86.

After emigrating to the United States, Rakosi had no further contact with his mother or her parents. Rakosi returned to Baja in search of his childhood home with his daughter Barbara and her husband Dan Nordby in the 1980s, however. While there, they chanced upon the building which had previously been the town’s synagogue (and is now the Baja public library), and found his mother and grandmother’s names listed on a monument to local Jews murdered during the Second World War:

We were walking down the street, and I see a big new building there, a synagogue. First of all, it was a new building; and, then, a big synagogue? I couldn’t understand. Ninety percent of the Jews had been killed at Auschwitz. How could it be? So, we walked in and I learned that it was no longer a synagogue, because there weren’t any Jews left. The building had been converted into a public library, but there was a Jewish altar at one end. And the librarian told me that—I no longer had enough Hungarian to talk to her in Hungarian, but I could manage the German pretty well—that there was one Jew who worshipped every Friday night at the altar there. So, I asked the librarian, “How come there is this synagogue, a big new synagogue, here?” She said, “We thought the Jews would come back to Baja, that they simply had left, fled.” …

Anyhow, then we were walking out and there was this long stone plaque, a handsome plaque outside the building. It was like a wall. It had many names engraved on it. I was going to go on, I wasn’t going to pay any attention to it, but I paused. “Let’s see what’s here.” Auschwitz was written on it. I looked down and I see the names of my grandmother and my mother.15See: Flóra and Róza Steiner: http://data.jewishgen.org/imagedata/hungary/holocaust/Baja16.jpg. So that was how I learned that they had been killed in Auschwitz.

So, that was it. Well, the death of my natural mother didn’t mean that much to me because I really had had no personal relationship to her; it had all been with my grandmother. My grandfather must have died before Auschwitz.16Oral History, 202. Another variant of the story can also be found earlier in this oral history document: “I went back with my daughter and son-in-law, and we went back to Baja, partly in order to find out what had happened to my family. So, we went to the city hall, but during the Communist regime, they had transferred all of the birth records to Budapest, so I couldn’t find out anything, but when I was walking down the street, I immediately recognized the houses, the kind of houses they were. So, we were walking down the street, and all of a sudden I see a synagogue there, a very handsome, rather new synagogue. Well, after the Holocaust, how could there be a brand-new synagogue in a city? So, we went inside and it turned out that they had transformed it into a library. So I was talking to the librarian who—I didn’t remember much Hungarian anymore. So I tried talking in German, and we got along fairly well. So I said, “How come there’s a synagogue here?” She said, “We thought that the Jews would come back.” Well, they had all been killed. There was only one single Jew left in the whole city of Baja. Everybody had been killed, sent to Auschwitz or other places. But, it shows—and this will interest you—that not everybody there was anti-Semitic, interested in killing Jews. They really thought that Jews had gone away to work somewhere, and this was the way to invite them back. It was an eye-opener for me. This is a dramatic story actually. Just one Jew. They had set up a tabernacle at one end of the library, and this single Jew, who apparently didn’t have a family anymore, used to come to Friday night services and perform the rituals. … So my daughter and I, and Dan, my son-in-law, walk outside, and I see there’s a wall there and some names inscribed carved into the wall, and just for the hell of it, I looked to see who’s there. Well, that’s how I discovered that my mother and grandmother had been killed in Auschwitz. Apparently my grandfather had died before that(6-7).

After leaving Baja in 1910, Rose, Lester, and Carl made stops in Budapest and Vienna before embarking on the long transatlantic journey. The family went second-class, which impressed itself clearly upon Rakosi’s memory, as did the fact that he became sick after nearly every meal of the long voyage. The ship arrived at Ellis Island, where the two boys completed a nerve-wracking health examination (Lester was slender and suffered from kyphosis) and passed through the immigration desk to life on a new continent.17Rakosi describes the stress of this health screening in his Autobiography: “There into what looked like an enormous, barren barracks, the immigrants poured and stood around, waiting nervously in their best clothes to check out their papers and to go through the required medical examination, and it hit them head-on for the first time that no one knew exactly what state of health they had to be in order to pass” (199).

During the journey from Baja to Chicago, the two boys began to get to know their “father’s wife” (she had not yet come to be felt as their step-mother), forming the initial bonds for what would be one of the most important relationships of Carl’s young life. Rakosi would later recall his stepmother as “not a woman of great natural warmth, but a tremendously gutsy, courageous woman, very solid in her feelings and thinking. Not much of a thinker, but enough.”18Oral History, 4.

A MIDWESTERN CHILDHOOD

Once they disembarked in the United States, the family lived in Chicago for about a year. In 1911, Leopold borrowed capital and equipment from Moore and Evans, his previous employers, and opened a small jewelry and watch repair shop in Gary, Indiana, a town of about 17,000 inhabitants located roughly thirty miles southeast of Chicago. As a child, Rakosi faced a very rapid assimilation into an entirely new and bewildering culture. This assimilation also had a linguistic component. Rakosi’s first language had been Hungarian, and his parents spoke Hungarian and German in the home.19In a letter to Andrew Crozier, Rakosi wrote: “My first language was Hungarian, but all educated Hungarians in those days spoke German, so I heard German at home in Kenosha too, and my ear for its natural cadence has never left me.” (UCSD Special Collections, MSS 0355, Box 4, Folder 5. Regarding his rapid immersion in a new linguistic and educational context, he told Kimberly Bird in 2002:

I started out not knowing one word of English, not a single word. I remember in Gary I had to pick up English immediately, and a little kid picks it up on the playground. … Gary at that time had a very progressive education system. They would test you and put you in the grade the test showed you belonged. … [O]ne day someone comes into the classroom and says they want to see me in the principal’s office. So I go to the principal’s office. The principal tells me, “Well, we’re going to change your class; we’re going to put you in this other class.” This other class was a year ahead. After about three or four weeks, I get another call to the principal’s office. This time I’m put into another class, a still higher class. So, I’m pushed around two years in just a few weeks time. I’m now in a class where I’m the littlest guy.20Bird, Oral History, 11. He gives a similar account in his autobiography: “Gary’s school system was better than you’d expect in such a rough steel town. That was because it happened to have a bold, innovative superintendent at the time who assigned children to grade levels not on the basis of age but mental ability. Thus, one day I was sent to a room I had never seen before and given a test; I had not the foggiest notion why. The next day I was called out of class to the principal’s office and told I was going to be moved ahead a grade. I couldn’t understand it. Then a month later, the same thing, another grade ahead. I had no difficulty doing the work in the upper grades, but now everybody in the class was two years older than I, and that did make a difference in my life because henceforth everybody in class would always be two years older and bigger and I would always be two years younger and smaller, even at the university” (199-200).

In a 1985 letter to a reader from Gary, Indiana, Rakosi wrote of his youthful introduction to race relations in the Midwest:

I remember the steel mills, of course, but in addition a terrifying experience on the school playground on day: five huge, wild-eyed black boys, shrieking war cries and wielding clubs with nails, driving all the white kids off the premises. That was my first sight of blacks.21Rakosi spoke of a similar memory with Kimberly Bird late in life: “on the playground in Gary, it was a terrifying experience, because the steel workers were big guys, and they had big sons, and they were mostly black at that time, I remember, and these guys would come running out with brickbats, or wooden bats with nails in them and come at you, and they would take over the whole playground. You wouldn’t dare go out to play there.” (Oral History, 11)

Another memory. It’s a very hot night. We’re all sitting outdoors on the street and a little black puppy comes running up, his tail wagging joyously. That was Teddy, and love at first sight, for him too. He stayed with us until we were grown.22Letter to Jim Gross, 12 June 1985. UW Madison Special Collections, Box 2, Folder 37.

In a letter to his granddaughter Jennifer in 1996, Rakosi remembered Teddy as

my first dog, a black and white puppy who came into my life one hot summer evening in Gary, Indiana when I was about seven years old. We were sitting outside my dad’s store … to get away from the heat inside when this little puppy came wobbling up to us kids with his tail wagging a mile a minute and complete trust and hope in his eyes. At last he had found us, he said with his tail. Talk about love at first sight! Since he was a stray, he instantly became a part of the family.23Carl Rakosi papers, Mandeville Special Collections, UCSD, MSS 355, Box 8, Folder 31.

While they stayed long enough for Carl to learn English and acquire a puppy, Leopold struggled to establish his business in Gary, and in 1912 the family moved to Kenosha, Wisconsin, a rapidly growing industrial town located about 100 miles northwest of Gary and 65 miles north of Chicago.24Kenosha’s population in 1880 was just over 4,000 people. By 1910 in had grown to over 21,000, and to more than 40,000 by 1920, meaning that it had sustained an average annual growth rate of nearly 6% for 40 years.

Following their move to Wisconsin, Leopold and Rose lived in a small apartment above their shop at 317 Orange Street. The family would later move to 61 North Main Street, with Leopold owning and operated a store in a modest brick building located at 5040 Sixth Avenue, a working-class neighborhood very near to the Kenosha Harbor on Lake Michigan. Leopold’s business letterhead identified Leopold as an “expert watchmaker and jeweler” and indicated that the shop, established in 1915, carried “diamonds, watches, jewelry, clocks, silverware, chinaware and optical goods.”

Rakosi remembered his family home as loving and supportive, but far from affluent. Money was always tight, and his parents scraped by from their month-to-month earnings. Rakosi would later write that his parents’ concern over their precarious financial situation “locked in and dominated their lives, subsuming their softer, convivial qualities. It locked me in, too. It locked me into a lifelong concern about making a living and affected my personal habits and the way I deal with practical matters.”25Autobiography, 200.

Rakosi’s older brother Lester had something of a tragic life. Born with a spinal deformity that left him with a noticeably hunched back, Lester did not get along well with his parents and did not apply himself well at school, although Carl remembered him as being very intelligent. He eventually learned watchmaking as a trade, like his father, and for many years ran a modest business repairing watches and working for a jewelers in Milwaukee. Lester never married, and died of cancer in July of 1958. He was buried in Spring Hill, a Jewish cemetery in West Milwaukee’s Story Hill neighborhood.

At the time that Carl and Lester were growing up there, Kenosha was mainly populated by people of German and Polish descent, and the economic life of Kenosha was dominated by two factories at opposite ends of town: the Simmons bed factory and the Nash automobile factory. Rakosi’s first “real” job, as a fourteen-year-old, was in the spring department at Simmons:

[T]he springs were spread out on some kind of a mat. Then you had to pull the springs tight and connect them to a hook, and you did that constantly, all day long, and your hands would be bloody after a while. There was a tray in front of you with lye, some solution of lye, because lye was probably too strong, but you’d dip your hands in this lye, oh, it would burn like fire. So, you had that experience for three months. It made a deep impression on me.26Oral History, 16.

There was a small Jewish community in Kenosha (Rakosi remembers it consisting of fewer than one hundred people) and an Orthodox synagogue, which the family attended. While Carl had a bar mitzvah upon coming of age, he recalled having only “very rudimentary” religious instruction, learning just enough Hebrew pronunciation as to be able to perform the expected readings.27Oral History, 28.

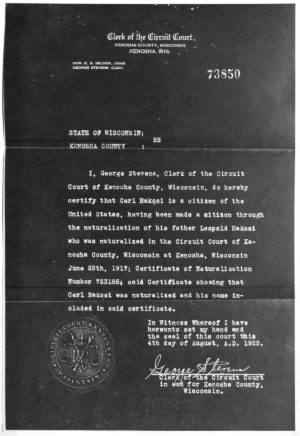

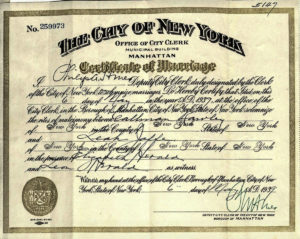

Certification of Rakosi’s naturalization as a citizen of the United States in 1917 (document issued in 1925). Original held by UCSD Special Collections, MS 355, Box 4, Folder 4.

Kenosha was also the place where Carl ‘became American,’ linguistically, culturally, and officially. On June 25, 1917 the entire Rakosi family was officially naturalized as American citizens by the Kenosha County Circuit Court. Carl felt fairly well assimilated, remembering that apart from being keenly aware of his small stature, his teen years had been pretty typical for a middle-class Midwesterner:

I was one of them, playing baseball and basketball and soccer and ice hockey, and swimming and roller-skating and ice-skating, flying along in long musical lines, and riding a bike without hands, all my natural medium—my song of summer, turned crystal in winter. I was utterly content and absorbed.

After school I found odd jobs. I washed dishes in an ice-cream parlor, I did menial chores in a barbershop, things like that. … I was in fact an all-American boy.28Autobiography, 200.

In addition to his sporting and social interests, one of the most important influences on Rakosi’s adolescent development was his discovery of Kenosha’s Gilbert M. Simmons Memorial Library, an attractive public library housed in a spacious neoclassical building designed by the Chicago architect Daniel Hudson Burnham. Though his father had high regard for learning, there were no books in the Rakosi home, so the discovery of the public library represented an entry into an enormous, majestic new world for the teenaged Carl.29”Although my father and stepmother were intelligent and had a high regard for learning (he had a European’s great respect for culture), she was too practical and literal to be interested in more than a newspaper, and his eyes at the end of a day were too tired to be able to read. Thus, there were no books in our home.” (Autobiography, 200). In an autobiographical account of his life, Rakosi called the library “my secret home and my secret vice,” and stated that:

I read everything, everything. And I found there the mental universe which suited me, and I discovered its scope and depth and excitement, but I had no one to share this with or the wild nature of my excitement.30Autobiography, 201.

The Gilbert M. Simmons Memorial Library in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Photograph taken by Mary Ellen Wietczykowski in 1971.

In a 1981 letter to an admiring reader from Kenosha, Rakosi described his memories of the library with great enthusiasm:

What a library that was in my day! What magic! I used to rush there from school, then slow to a genteel walk as I entered the vestibule, and slip into the stacks on tiptoe, making myself as small as possible, avoiding at all cost a look at the librarian, for that might make her question my entrance. For I never got over the feeling that there was a mistake somewhere, it couldn’t be that all those marvellous [sic] books, row after row, in that dim light, which seemed somehow appropriate to their mysterious contents, were there for me, and that if it were found out what I was doing ….. touching, handling, poring …. , a halt would be put to it. I realized, of course, that the opposite was the case: the librarians positively beamed at the little kid who came out of the stacks with an armful of Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, Max Stirner, Huneker, Dickens, Chekhov, George Eliot. I was their prize habitue, their precocious reader, a living proof that what they were doing was worthwhile. Nevertheless, I never quite got over the feeling that there was something not quite licit about extracting so much out of those books. The City Fathers just didn’t know; so I had to be careful not to betray the secret when I emerged from the magic grotto in the back. But I couldn’t hide the excitement on my face, and it must have been that too which made the librarians beam.31Letter from Carl Rakosi to John Kingsley Shannon, October 12, 1981, in UW-Madison Special Collections. Box 2, Folder 31.

Rakosi did most of his reading outside of his home, surreptitiously, believing that his burgeoning literary interests would be ridiculed by other townspeople and misunderstood by his pragmatic, practically-minded parents were they to become public. As to his earliest literary interests, he told Andrew Crozier that his first reading

was into English, not American literature: Shakespeare, Chaucer, Keats ….. Blake, Burns and Herrick came later … then suddenly Yeats and those late 19th Century poets with the haunting, sad cadences, Lionel Johnson and Ernest Dawson. This was not by choice but simply the order of priority in the American school system.32”Answers to Questions from Andrew Crozier,” UCSD Special Collections, MSS 0355, Box 4, Folder 5.

Though Rakosi loved books, his first and deepest affinity was for music, an enthusiasm which he was not ashamed to pursue openly at home. As children, both he and his brother saved for several months in order to buy a mandolin and instruction manuals so that they could teach themselves to play, and Rakosi asserted late in life that “If we had lived in a big city, and if my folks could have afforded it, I would have become a musician and a composer rather than a poet. To this day music means at least as much to me as poetry.”33Oral History, 18.

The origins of Rakosi’s identification as anything more than just a reader of literature were in high senior year of high school, when he wrote an essay on English Victorian poet and novelist George Meredith. He would later recall: “To my wonderment the teacher wrote back a long enthusiastic response as to an intellectual equal, with comment after comment indicating that she respected my literary mind. That is how I learned that I had one and that I could express it.”34Autobiography, 201. In later accounts of his life, Rakosi would consistently credit this experience as the first significant one in the formation of his desire to become a writer.

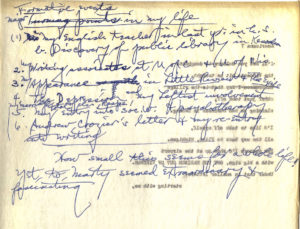

“Major formative events in my life.” Original held in Mandeville Special Collections, MSS 355, Box 4, Folder 4.

For example, while compiling notes in response to questions about his writing life from Marty Rosenblum, who was then writing his dissertation on Rakosi’s poetry, Rakosi made the following handwritten sketch of “Major formative events in my life”:

1a. My English teacher in last yr. in h.s.

b. Discovery of public library in Kenosha2. My writing associates at U of C[hicago] & U of Wisc[onsin]

3. My appearance in Little Review & The Exile

4. The Depression and my Leftist involvement

my marriage & cli[nical] resp[onsibilitie]s.5. My total entry into soc[ial] w[ork] & psychotherapy

6. Andrew Crozier’s letter & my re-entry into writing

How small this seems for a whole life, yet to Marty seemed extraordinary & fascinating.35Carl Rakosi collection, Mandeville Special Collections, UCSD, MSS 355, Box 4, Folder 4.

More details regarding Rakosi’s development as a writer and a history of his publications can be found elsewhere on this site.

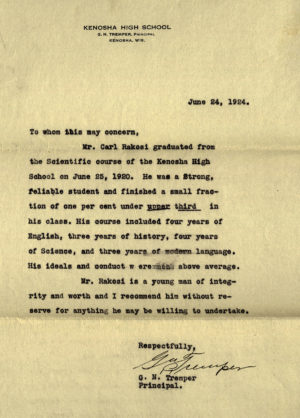

COLLEGE

In 1920, following his graduation at age 16 from Kenosha High School near the upper third of his graduating class, Rakosi enrolled at the University of Chicago. The transition from life as a teenager in Kenosha to life on the campus of a prestigious private university in a city of nearly three million people was mixed for Rakosi, presenting opportunities that were awesome, daunting, and intimidating. Near the end of his life, he described some of the more memorable parts of this transition:

I’m sixteen years old, and I go to Chicago, which is … a working-class, Middle Western city, very industrial in its character, but the campus there puts you into a different world. The campus—the architecture, the buildings are modeled after either Cambridge or Oxford, I don’t know which. They are almost like cathedrals, semi-Gothic. It was my first exposure to that. I was overawed. I used to hang around the International House there, and that was a fascinating place to be. To my amazement—you know that I come from Kenosha, I am sixteen years old. I had never met graduate students from India before, from all over the world. They came to the International House. There was great talk there.36Oral History, 189.

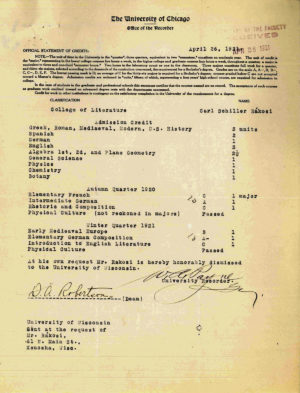

In his first quarter, Rakosi took courses in elementary French, intermediate German, and rhetoric and composition. In the winter quarter, Rakosi took a course in early Medieval European history, elementary German composition, and an introductory English literature course taught by Robert Morss Lovett, a well-known scholar who had served as the dean of the junior college for more than a decade. It was in Lovett’s course that Rakosi first began to write poetry, and Rakosi later described himself as being influenced by two of his fellow students: George Schuyler, “who wrote poems in a style like Rudyard Kipling’s, very robust,” and would later go on to be a prominent African-American journalist, and an unnamed older Japanese man who “wrote quite short poems in the style of a haiku”.37Oral History, 21. Rakosi would later recall “like the invisible way I had learned English, one day I was a reader of literature and the next day, there was the knowledge, as if it had always been there, that I wanted to be a writer and that I could best express myself in poetry, not prose. It happened in this class [the course he took from Lovett].”38Autobiography, 202. In a 2002 interview, he remembered that it was at this time that he first “knew without any reasoning it out in any way that I was going to be a poet—that my calling would be that of a poet.”39Oral History, 21.

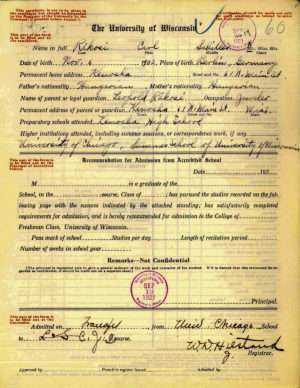

Rakosi’s transcript from the University of Chicago and release for transfer to the University of Wisconsin.

While he enjoyed his studies, Rakosi struggled to make friends, due both to his youth and because he lived in a dormitory on campus, which quickly became a social desert after classes let out. He told an interviewer that “I was too lonesome in Chicago. I had no friends and the students never hung around on the campus after class. I couldn’t meet friends; there was nobody there. So I transferred to Madison, because I don’t think that I had to pay any fee in Madison at that time. … At that time, I think that Wisconsin was the most progressive university in the country, and the most progressive in their ideas about education.”40Oral History, 22-23.

Rakosi’s official admission to the University of Wisconsin as a transfer student from the University of Chicago, dated September 19, 1921.

In April 1921, Rakosi left the University of Chicago and transferred to the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he enrolled in summer school and was admitted as a full-time student beginning in Fall 1921. In contrast to his experience of the imposing intellectual environment at Chicago, he found his peers at Madison quite different, recalling that

There’s nothing awesome about the campus there. On the contrary. The student body were mostly kids from the farms in Wisconsin. … I didn’t feel that the students in Madison at that time were real students. They were there because they could afford to go to college, but they were primarily interested in girls–the men–and similarly, I suppose, the girls in men. … They were interested in anything but studies and learning.41Oral History, 189-190.

Rakosi did not feel that he fit particularly well with the general student body at this time, writing:

Madison in those days was a very clean, respectable small town of one-family homes with well-kept lawns. The University had some ten thousand students, mostly from Wisconsin farms and small towns, blond young Babbitts of North European stock, their hair cropped close. It was a place for youth fed on fresh country milk and Iowa corn where time was suspended and they looked each other over and saw that they were comely, and flirted and horsed around, and the big events were football and the Big Ten pennant ahead. And standing guard was a smugness hard to imagine these days, although Nancy Reagan comes pretty close to it.

Entered I, poor little Jewish boy, stewing in an inner life, sensitive, mystical, with Tolstoyan idealism and Nietzschian yearnings, feeling as if I had been branded by a stigma.42”Scenes from My Life” in Collected Prose, 90.

While Rakosi didn’t see himself reflected very well in the broader student body or university culture in Madison, there were a few social factors which helped him to achieve a much higher degree of integration than he had enjoyed at Chicago. The first of these was a change to his living situation. Instead of the university dormitory he had occupied at Chicago, in Madison he moved in with two older undergraduates he knew from the Jewish community in Kenosha. He and his roommates took their meals with a young Jewish widow with several small children whose home cooking and convivial hospitality did much to put Rakosi at ease and helped him feel that he arrived in a more socially comfortable situation.43He wrote in an autobiographical account of his life: “As soon as we sat down to her table and saw spread out before us all the dishes heaped high, steaming hot from the kitchen, and rich spicy smells all around, like at home, we unwound and started jabbering away, joking and bantering and laughing, and she stood by our chairs with a big smile, as if entranced, and took in every word, laughing hard along with us and making herself a part of us without intruding. How she enjoyed seeing us eat heartily! And when the food ran out, how happily she ran into the kitchen for more. The place had the jovial spirit of Dickens when she was there, and the warm, giving spirit of a genial mother who knew how to keep hands off. How much she gave us! And how uncertain her own future was” (Autobiography, 202).

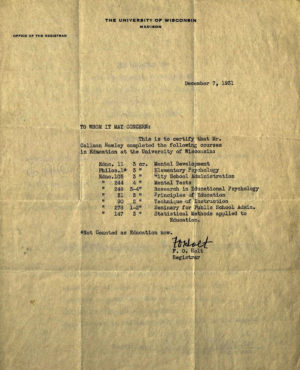

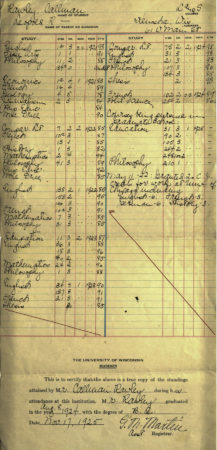

Carl Rakosi/Callman Rawley’s undergraduate transcript from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, issued November 17, 1925.

Second, the University of Wisconsin at Madison was at that time actively developing its growing reputation as a leader in progressive principles of education, which both appealed to and shaped Rakosi’s political idealism. While he may have expressed contempt for many of his fellow undergraduates, he had great respect for many of the professors then teaching there, and he took courses from such luminaries as William Ellery Leonard, one of the region’s most prominent poets and scholars, who had developed an unusual English course in which he taught what would now be called creative writing; the philosopher Max Carl Otto; and the sociologist E.A. Ross.

Most importantly for Rakosi, however, was the continued development of his identity as a writer and the formation of deep friendships with other students in Madison who shared his literary interests and ambitions. Rakosi’s deepest friendships in Madison were with Leon Serabian [Herald] (an Armenian immigrant and part-time student), Kenneth Fearing (with whom he lived as a roommate), and Margery Latimer (a young protégé of Zona Gale’s from Portage, Wisconsin), each of whom would go on to achieve some measure of literary success. He was also acquainted with Horace Gregory and Marya Zaturenska, both of whom lived in Madison at that time.44He describes these relationships in greater detail in “Scenes from My Life,” a brief biographical essay in Collected Prose (the college friendship section occurs pp. 88-104). Although he was strongly attracted to philosophy and sociology, Rakosi ultimately decided to major in English, and, along with Fearing and Latimer, served as an editor of The Wisconsin Literary Magazine, a student publication where Rakosi’s first published poems appeared.45In March 1924, shortly before his and Rakosi’s scheduled graduation, Fearing was forced to resign his position as the editor-in-chief of the magazine by disgruntled university administrators. The student newspaper The Daily Cardinal reported that “it was held that the editorial policy of the magazine has been irritatingly satirical and intolerably misanthropic, sour and biting.”

In many ways, Rakosi must certainly cut something of a strange figure in Madison during those years, not only by dint of his age and family background, but also because of his personality. Writing in the Wisconsin Alumnus magazine, a classmate remembered Rakosi as “a little fellow with an intense manner and tragic eyes, whose soulful verse appeared in the Literary Magazine,” and related a humorous story in which Rakosi comes off as sweet but otherworldly.46Wisconsin Alumnus, 22. Rakosi also appeared as a character in Latimer’s 1930 roman à clef This is My Body as Schevel Pukalski, a young, ambitious, uncompromising modern poet, whose ideals and harshness put him at odds with his more conventional literary peers:

She recognized a boy from her English class. He was Schevel Pukalski. She had seen him showing Mr. Beers a book of his poems one day. When he left the room he had clapped his hand over his forehead and hurried stiffly down the hall. He always had an anguished pucker between his brows and his red mouth was drawn up as if it hurt him. Now he sat looking at his knees.

“Mr. Pukalski,” said one of the girls on the couch, “I just loved that poem you read in class the other day.”

He looked at her coldly. “You women certainly have a limited vocabulary.”

They began giggling. The springs of the couch screeched as the girls flounced about, making themselves comfortable.

“No, I mean it. Everything is always lovely and adorable and grand and just lovely.” He held his mouth open for a minute, his red lips scornful. “I should think before you even try to write you’d learn words with meaning and strength to them.”

After another student reads a poem and shares some fawning praise he claims to have received from a “professor in a southern college,” Pukalski erupts:

“Say, cut out that crap!” cried Schevel. He clapped his hands over his ears. “It’s bad enough to listen to those cliches in the classroom. Had I better read now?” he asked stonily. He opened his papers. The poem was short and full of odd words and sensations. The silence he received was terrible. He looked around at them, his chin held high. “Of course you don’t understand,” he said proudly. “But I am like Yeats. Absolutely without compromise.” He opened “Thus Spake Zarathustra” and began reading.

“Cut it out, Pukalski,” said one of the men; but he went on in low throaty tones.47This is My Body, 162-165.

Later in the book, Latimer describes fierce resistance to Pukalski’s being elected as an editor of a student literary journal and describes the savage dismissal of a Pukalski-submitted poem when it is read among a group of student editors. In the conversation, Pukalski is dismissed as “nothing but a child” who says “embarrassing things in class about Wordsworth and these new poets … being as good or better … than the old ones,” and is defended only by the characters representing Latimer and Fearing.48This is My Body, 203. Elsewhere in her novel, Latimer describes Pukalski’s ambitious desire to get his work published, start his own magazine, and hold onto his self-belief and idealism in the face of the world-weary cynicism of Fearing’s character. She also describes his enduring public humiliation from an English professor (probably based on Leonard) who interrupts his reading of an essay in class to make several disparaging remarks.

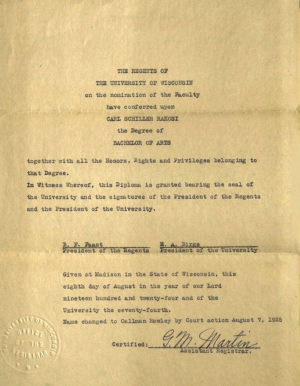

Despite the sometimes awkward fit between this young, idealistic poet of Hungarian Jewish descent and the broader Babbitesque environs at Madison, Rakosi graduated in 1924 with his B.A. in English. Following his graduation, Rakosi began almost immediately to worry about his job prospects. As he recalled to Tom Delany and Olivier Broussard in 2001:

I had given no thought to how I was going to make a living, so as graduation approached, I was in a panic. I had to return to Kenosha and wait for something to turn up and to my great surprise, something did. In my desperation it seemed like a miracle. I came across an announcement that the American Association of Social Workers was interviewing applicants in Chicago for work-study positions. At that time there were almost no men in the field and they were especially interested in recruiting men. I didn’t have the slightest idea what social work was then, but it didn’t matter. I could now make a living and I leaped at the chance and they accepted me very cordially and with great warmth in Chicago.49http://jacketmagazine.com/25/rak-devan.html

His interview in Chicago led to his taking a job in Cleveland, Ohio as a social worker-in-training with Family Service, a family counseling agency that partnered with Case Western Reserve University to train social workers. While in Cleveland he met and appears to have dated or at least formed a deep friendship with Mary Biggs, a local woman who worked as a hairdresser in town. Of this period of his life, would later recall:

The Associated Charities needed a trainee right away, so I moved at once to Cleveland. This was 1924, before a professional postgraduate curriculum and faculty for social work had been developed in universities. One was just starting at Western Reserve in conjunction with the Associated Charities. Members of the agency’s supervisory staff taught courses in theory part of the time and supervised and helped the trainees with their cases the rest of the time. The trainee was paid a modest salary. I found the courses rather dull but immediately became deeply involved with my clients, more deeply and disinterestedly than I had ever been involved with anyone before. And I discovered in myself a great urge to listen deeply to their distress, to understand it, my whole attention in it, and be helpful. In this I discovered a great excitement and a gay self-fulfillment unknown to me before.50Autobiography, 205.

He also had his first taste of actual social work in Cleveland:

I remember as clearly as if it happened yesterday, my first client. It was in a poor neighborhood, I rang the doorbell of his house, and somebody yelled from upstairs, “Come on up.” So, I walk upstairs and I find a black man lying in bed. He had things rigged up so he could open the door, by pushing a button—that sort of thing—and I started to deal with his problems and his situation and I got hooked. I knew then that that was going to be my profession, that there was a deep impulse in me to be helpful to people in need. There was something fulfilling in doing that.51Oral History, 44.

Although Rakosi quickly fell in love with the work and with his clients, he still thought of himself primarily as a poet, and began to feel divided between his writing impulses and the powerful psychic and emotional demands of social work, a conflict which would dominate his life for at least the next decade. Feeling restless in Cleveland, and believing that New York City would be both more exciting and provide him with more time and opportunity for his writing, Rakosi quit his job in Cleveland within a year and moved to New York in late 1924/early 1925. This decision was a very difficult one for him, as he had formed deep attachments to the social work he had been doing and possible also with Biggs. It’s unclear exactly how serious Rakosi regarded his relationship with Biggs, as the tone of her letters indicates that her affection for him may have been stronger than his for her, but he did visit Biggs again during a brief trip to Cleveland in late summer 1927, though their correspondence appears to have stopped shortly thereafter.52Several letters from Biggs to Rakosi (written between February 1926 and September 1927) are held with Rakosi’s papers at UCSD: MSS 0355, Box 1, Folder 21.

Shortly after his arrival in New York City, Rakosi experienced his first major literary success, thanks in large part to encouragement from Margery Latimer. Upon his move to New York City, Latimer had advised Rakosi to call on Jane Heap, the famed editor of The Little Review. Like many aspiring writers of his generation, Rakosi was somewhat in awe of Heap’s magazine, which not many years before had serially published James Joyce’s Ulysses to great controversy, and was then publishing writers like W.B. Yeats, Ezra Pound, and T.S. Eliot. Rakosi did summon up the courage to visit Heap at her Greenwich Village offices, and when she invited him in, he presented her with a manuscript of his poems. She agreed on first sight to publish them and printing three of Rakosi’s poems in the Spring 1925 issue of The Little Review.53They were “Sittingroom by Patinka,” “The January of a Gnat,” and “Flora and the Ogre.” Rakosi describes this meeting in some detail in “Scenes from My Life” in his Collected Prose, 90. Rakosi was elated, later describing his publication in Heap’s magazine as “one of the great moments of my life. To get into the Little Review was the achievement.”54Oral History, 31.

CHOOSING A CAREER

Restless, young, and eager for adventure, Rakosi became briefly obsessed with going to sea. Enlisting Kenneth Fearing’s help in forging a document of prior service so that it would look like he had previous experience in the merchant marine, Rakosi was taken aboard a merchant ship carrying cargo to Australia as a messboy in 1925. The hard work and strict class structure of life aboard a merchant ship quickly stripped him of any romantic illusions he may have been harboring regarding the seafaring life, and following his return to New York City, he took a job as a boys’ counselor with The Jewish Board of Guardians, a treatment center for psychologically disturbed and delinquent boys. He shared an office at this time with Harmon S. [“Sol” or “Sollie”] Ephron, who would go on to become one of the founders of the Association of Advancement of Psychoanalysis and the American Institute for Psychoanalysis. The two men became close friends, corresponding regularly until Ephron’s death in 1992, and Ephron’s wife Judith would be instrumental in helping Rakosi find work upon his return to New York City in 1935.

Rakosi did write poetry while in New York, but continued to keenly feel the conflicting demands on his time and energy made by his art and professional social work. He would later describe the job as “too much of a good thing, too absorbing, too demanding, too rigorous. It was making it hard for me write.”55Autobiography, 205. Still harboring the desire to become a poet, Rakosi would later write that “in desperation” he decided to try pursuing a career that he found less exciting, “like teaching or industrial psychology.”

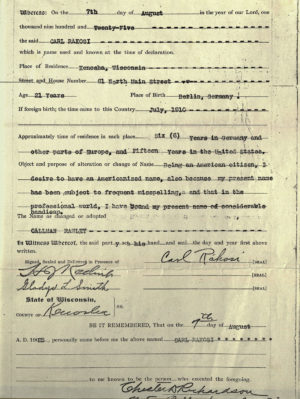

After less than a year in New York City, Rakosi returned to Madison, enrolling in a master’s degree program in industrial psychology (then being offered by the Education department) at the University of Wisconsin in the fall of 1925. Having recently reached the age of majority, he changed his name legally to Callman Rawley on August 7, 1925. On the application itself, where the form asked for the “Object and purpose of alteration or change of name,” Rakosi wrote “Being an American citizen, I desire to have an Americanized name, also because my present name has been subject to frequent misspelling, and that in the professional world, I have found my present name of considerable handicap.”

Rakosi’s motives for this change were various; but it seems that, much like his father and uncle before him, he saw professional advantages in removing a marker of Jewishness or foreignness in a society prejudiced against both Jews and certain kinds of foreigners, and that further, he wished to continue writing but did not want his professional associates to know of this other identity.56In his published autobiography he says “For one thing, Rakosi was forever being mispronounced and misspelled, but the main reason was that I didn’t think anyone with a foreign name would be hired, the atmosphere was such in English departments in those days. I kept Rakosi as my pen name, however, and no one who knew me as one, knew me as the other. This suited my purpose, as I didn’t want professional colleagues to know that I was a writer. It was not just that I wanted to keep that private: I thought it would color and contaminate their perception of my understanding and practice of the profession” (Autobiography, 205-206). With this change, Rakosi began the bifurcation of his identity, preserving Carl Rakosi as a private, literary self, and embarking on a public, professional career in the persona of Callman Rawley. Though most who would meet him over the next 45 years would know him as Callman Rawley and his wife and children would take on the Rawley surname, he would tell an interviewer near the end of his life: “I have much more attachment to Rakosi, because it was really my family name, and it’s my literary self.”57Oral History, 14.

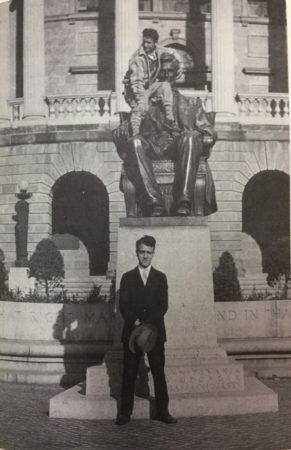

Carl Rakosi standing in front of the Lincoln statue on Bascom Hill at UW-Madison, 1925. Rakosi’s friend Morris Morrison is climbing in Lincoln’s lap.

While in Madison for graduate school, Rakosi founded and edited The Issue: A Forum of Student Opinion, a short-lived satirical magazine with Alexander Schindler, a Swiss medical student who would later become a prominent doctor. During his first semester of graduate school, “The Holy Bonds,” a short poem about marriage, was published in the December 23, 1925 issue of The Nation, but apart from these efforts, much of his time was consumed by his course work and professionalization efforts.

During the Fall 1925 and Winter 1926 semesters, Rawley completed a number of graduate courses in education and psychology, earning his masters of arts degree at the end of the Spring 1926 semester.

Upon completion of his master’s degree, Rawley took a job as a psychologist in the personnel department of the Milwaukee Electric, Railway & Light Company. The position entailed using physical equipment to test motormen’s responses to simulated experiences and to form psychological profiles of these employees based on their performance. He later recalled

The director of that program was an older man already in his sixties, quite a gentleman. He had built up a safety testing program for the streetcar company, which he had developed himself, a system in which there was the interior of a streetcar with a motorman and a screen on which images would be flashed, and the motorman would be expected to react to a sudden turn or sudden stop, and his reaction time would be measured, and his efficiency would be noted. It was a safety kind of instrument device. I didn’t have anything to do with the creation of that, but I operated the thing with motormen.58Oral History, 193.

Though he had intended to pursue a “less exciting” career in order to give him the time and energy to devote to writing, he appears to have been a little too successful with this job. While he found Milwaukee “a pleasant place to be,” he found the work “deadly dull” and left within a year to take a job as a psychologist in the personnel department of Bloomingdale’s department store in New York City. After the store experienced poor sales over the 1926 holiday season, he was fired (along with the superintendent who had hired him). Following the loss of his job at Bloomingdale’s he returned to social work, taking a position early in 1927 as a family counselor with the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children in Boston, Massachusetts.

Upon moving to Boston, Rakosi took an apartment with three roommates, first living near the Massachusetts State House before briefly renting an apartment on Commonwealth Avenue. Rakosi enjoyed the city, recalling that “Boston was so different from the Middle West. It had so much history; it was almost like going to Europe.”59Oral History, 194.

The nature of his work as a social worker with children who had often been severely neglected or abused there meant that he had a close connection to the juvenile court there. Although he encountered a number of families in particularly dire situations and regularly worked on behalf of children living in great precariousness, Rakosi was particularly impressed with the humaneness and decency of the judge who presided over the court, a patrician gentleman from one of the old Boston families:

What I remember about my social work experience in Boston was the dignity of the juvenile court process, and really there was a certain decency about it that was quite wonderful, but it all emanated from the judge. I had great respect for the judge and the workings of the court. … I loved the way he looked and how he presided over the court with the children. He was really a benevolent, fatherly figure, but not a pushover, not soft. He relied on the judgment of the social workers on what to do in these cases.60Oral History, 194, 124.

Though he enjoyed this job immensely, Rawley still felt enormous conflict about his desire to have more time and leisure for writing. Having tried industrial psychology and found it lacking, and experiencing social work as too engrossing to afford the time and energy he needed for writing, he turned to his fallback plan of university teaching, hoping that it would be more conducive to his writerly ambitions.

In the fall of 1928, Rawley enrolled in the English Ph.D. program at the University of Texas at Austin, where he was assigned to teach freshman composition to engineering students from November 1928 through the end of the summer session in 1929. It did not go well. “You can’t teach literature to engineers,” Rakosi would later complain, “their imagination was made out of wood.”61Oral History, 194. To make matters worse, Rakosi found the English department at Texas to be an “awful, a sickening, sycophantic atmosphere. Death would be preferable.”62UCSD Special Collections, MSS 0355, Box 4, Folder 6. He would later explain:

The work was easier, all right, and there was time for my writing, but now it was the young prigs in the department I couldn’t stand. They acted as if they had brought Oxford to Austin, and unlike young professors these days, were so affected and British high-toned that I felt nauseated and was faced with having to spend the rest of my life with clones. I could see too that what I would be doing as a professor would be so specialized and of so little value except in English departments that I would be like Tom in the old English joke:

“What are you doing. Jack?”

“Oh, nothing.”

“And what are you doing, Tom?”

“I’m busy helping him.”63Autobiography, 207.

Dismayed by his experience in the literature department, Rawley enrolled in law school, where he enjoyed the curriculum, but was “scared off by the fierce competitiveness and boundless verbal fluency [required] at a moment’s notice, and again I quit.”64”Rakosi Chronology,” UCSD Special Collections, MSS 0355, Box 4, Folder 6. Still hopeful about the prospects of conducting a writer’s life while working as a teacher, Rawley took a job as an English teacher in San Jacinto High School in Houston, working evenings at the Rusk Settlement House as a group worker with Mexican immigrants. Though he loved his evening job, he quickly found that “the heavy teaching load and the disciplinary problems in my classes bec[a]me a nightmare. By this time I am sure that what I would like to do best of all, where I would have most control of my time, would be psychiatry. So during the summer vacations I return[ed] to the University in Austin to study the pre-medical sciences.”65”Rakosi Chronology,” UCSD Special Collections, MSS 0355, Box 4, Folder 6.

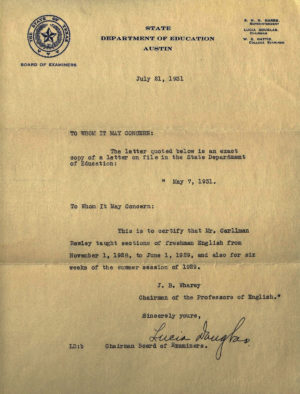

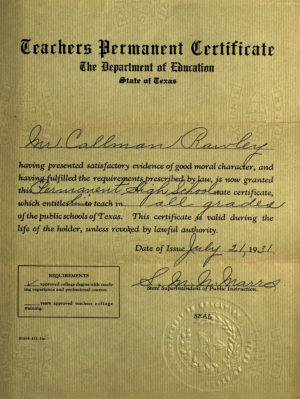

Callman Rawley’s permanent high school teaching certificate, issued by the Texas Department of Education on July 21, 1931. Original held by UCSD Special Collections, MSS 355, Box 4, Folder 4.

It also appears that though he had already left off teaching high school by this time, Rakosi had fulfilled all the legal requirements and received his certification as a permanent high school teacher in the state of Texas in July 1931, entitling him to teach in all grades of Texas’ public schools for as long as he liked.

RAKOSI AND ZUKOFSKY

Even as Callman Rawley wandered from job to job, exploring various graduate programs, Carl Rakosi continued to write and sporadically publish poems. It was while he was teaching high school English in Houston in the winter of 1930, in fact, that he received a letter from Louis Zukofsky, introducing himself and soliciting poems for a forthcoming issue of Poetry magazine on the recommendation of Ezra Pound. Zukofsky’s letter could not have arrived at a better time for the floundering Rakosi:

I had a job teaching English literature to high school seniors in Houston. What I thought would be a relatively easy, mild experience turned out to have a monstrous work load, and I loathed the students’ lack of interest and cutting up in class and the fixed Victorian course of study from which one was not allowed to deviate. Zukofsky’s letter came when I was in despair. I had tried every occupation I could think of in which I could make a living and still have time and mental energy to write without success. There was no place else to go. It seemed like the end of the line.66”An Interview with Carl Rakosi,” Conjunctions 11 (1988), 220.

Zukofsky and Pound had been corresponding for some time, with Pound consistently urging Zukofsky and others of his American correspondents to organize a group or movement of young, like-minded poets in the United States. While Zukofsky had shown much less enthusiasm (or entrepreneurial skill) for movement building than Pound had, Pound had cajoled Harriet Monroe into giving Zukofsky an issue of Poetry magazine in order to present his “new group.” Pound had never met Rakosi in person, but had published some of Rakosi’s poems in his short-lived magazine The Exile. Consequently, though he had no recent news on the Rakosi’s whereabouts, Pound duly forwarded on to Zukofsky his last known address is Kenosha, along with a warning that “Rakosi’ may be dead, I wish I cd. trace him” as he had sounded deeply depressed in their brief previous exchanges.67Pound/Zukofsky, 51.

Rakosi, though depressed, was decidedly not dead, and he and Zukofsky quickly established a warm epistolary friendship, with each finding succor and encouragement from the other. Rakosi later wrote:

[Zukofsky] had just come on as a teaching assistant in the English department at the University of Wisconsin and had discovered immediately that this was the wrong medium for him, the wrong place, the wrong responsibilities, the wrong people … I was in somewhat the same situation. I was beginning my second year as an English teacher in a Houston high school and was crushed by the teaching load and the disciplinary problems, and sick from alienation from it all. We had the desperate psychic problem, therefore, and consequently instant rapport.68”Notes to Zukofsky Letters,” UCSD Special Collections, MSS 0355, Box 11, Folder 12.

Zukofsky’s second letter to Rakosi was written on November 17, 1930 and contained high praise:

Permit me to say that your poems are the best in America–these U.S.A–that I have seen since, well 1926. But that doesn’t say what I want to say. And you gave up writing? Gave up—? …

My issue of “Poetry” is as much of a surprise to me as I suppose my invitation to you is to you. … My intention is to print 32 of the best unpublished material written in the last 10 years. Naturally, I should like to show off at least 8 poets–if I can’t find 12. Or at least six. But I do want to print as much of you as I can—say 5 to 7 pages, depending on other available genius. … What I don’t keep I’ll try to pass off on Hound and Horn, Pagany, Morada, or future issues of Poetry69Letter from Zukofsky to Rakosi, November 17, 1930. The originals of Zukofsky’s letters are now held at the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Texas. This passage quoted from Rakosi’s typed transcription in UCSD Special Collections, MSS 0355, Box 11, Folder 12.

Rakosi responded positively to Zukofsky’s initial letter, and Zukofsky used four of Rakosi’s poems to open the “Objectivists” issue of Poetry, presenting them just before a selection from his own “A”-7. He also included nine sections of Rakosi’s “A Journey Away” and the short poem “Parades” in his An ‘Objectivists’ Anthology published in 1932. After their initial contact, the two writers continued what Rakosi characterized as “a long, intensive correspondence on questions of poetics, mostly having to do with my own work” for the next several years and enjoyed regular social contact with each other from 1935 to 1940 when both men lived in New York City.70”Scenes from My Life” in Collected Prose, 107. In a 1984 letter to Burton Hatlen, Rakosi recalled:

I described LZ as a superlative editor. I should have added that, as he practiced it, editing was a form of high art, in the sense that he perceived quite clearly what, in my case, for example, my true literary character was and held me strictly to that. There was no question, therefore, of his teaching anything; I already knew. What he did instead was to put himself into the shoes of an intelligent reader and point out what was me and what was sham or derivative. But doing this is almost as rare as great poetry. Ever good editors are too walled-in by their pre-conceptions and their own personality and stylistic needs to perceive the other poet’s true literary character, let alone refrain from trying to re-do his poem as he thinks it should have been done. Since my literary character, naturally, at that age was not fully formed yet, what he did was very helpful. He did the same thing for the others too (except Reznikoff, as you noted), and particularly for Lorine Niedecker.71Letter from Carl Rakosi to Burton Hatlen, February 14, 1984. UCSD Special Collections, MSS 0355, Box 4, Folder 15.

Apart from Rexroth, Rakosi had little contact with other of the “Objectivists” until the 1960s and 1970s, when he befriended Oppen and Reznikoff, and met Bunting and Niedecker.72Rakosi writes penetratingly of his relationship with Zukofsky and his relationship to the label “Objectivist” in “Scenes from My Life” in Collected Prose, 104-108.

Though Zukofsky’s letters and the promise of publication in Poetry provided some much-needed encouragement to his flagging poetic ambitions, Rakosi was still in search of a meaningful career. In a 1983 letter to André Lefevere, who was then just about to take a teaching position at the University of Texas, Rakosi recalled his impressions of Texas and his general feelings about this time of his life:

I lived in Austin during the 1930s. It was then a city of about 50,000, very pleasant, with girls whose beauty used to drive me wild. There were not many blacks in Texas then but an unknown number, well over a million, of Mexicans, who were treated with contempt. I could never understand it because these mostly illiterate, very poor laborers had far more natural dignity and integrity than the Texans. I was a teaching assistant in the English Department then but that didn’t last long. I couldn’t stand the Anglophile affectations, the jostling for power, the sycophancy and the covert throat-cutting and got out before it was too late. Switched to medicine, which I studied at the Medical School in Galveston but had to give up eventually when my money ran out.73Carl Rakosi to André and Pat Lefevere, 12.20.83, UW-Madison, Box 2, Folder 30.

As his letter to Lefevere indicates, after a few years of teaching and taking pre-medical courses part-time, Rawley moved to Galveston in 1931 to study medicine at the University of Texas Medical School. Once again, Rawley enjoyed his course work and performed well academically (he felt particular pride in his having received A’s in each of his anatomy courses despite such squeamishness that he could never bear to perform the dissections himself), but felt deeply alienated from his fellow students, whom he described as “cultural dunderheads simpletons from the sticks, with no interests but getting through the medical school.”74”Rakosi Chronology,” UCSD Special Collections, MSS 0355, Box 4, Folder 4. At every turn, it seems, Rawley felt frustrated by finding a group of students more interested by items in their field of study, than outside of it. Not surprising to those of us who assume that people are going to school because they’re interested in the field they’re studying, but for Rakosi, who was continually educating himself in search of a side career that could subsidize his true (though non-paying) vocation, that of a poet, this is perhaps unsurprising.

In addition to his social isolation, Rawley began to run out of money to continue his studies. Since the medical school had no financial loan programs for needy students at that time, he gave up his study of psychiatry in 1932 and rode back north to Chicago on freight cars, traveling with a friend he had made at the University of Texas “partly for the experience, partly to save money.”75Autobiography, 207. Rakosi describes his experience riding the rails in some detail in his interview with Kimberly Bird (Oral History, 67-68, 214).

BEGINNING A CAREER IN SOCIAL WORK

Chicago

After leaving the study of psychiatry and riding the rails from Galveston to Chicago in 1932, Rawley returned to the field of social work, working in Chicago as a social worker providing services to the elderly for the Cook County Department of Public Welfare and taking graduate courses in social work at the University of Chicago.

New Orleans

In 1933, particularly concerned with unemployment and the plight of migrant laborers, Rawley took a job in New Orleans, Louisiana as a Director of Social Services in the new Federal Transient Bureau. His introduction to the different culture of the “Big Easy” began as early as his initial train ride to the city from Chicago:

I take the train in Chicago, in a twenty degree temperature, and I wind up in New Orleans, and it is about eighty-five, ninety degrees hot, so in that short time, it was a hundred-degree change. I’m young, I feel great. I pick up two women on the train who are from New Orleans. New Orleans then was a very fast town. By fast I mean, fast women. Sexual mores, very fast. Drinking, not in any repulsive way, it is almost like a different civilization down there. Talk about contrast, New Orleans was the place to be if you were young. So the first thing we do, the three of us, is go out to the racetrack. Apparently, they love to bet on the horses there. So, my first experience in New Orleans was at a racetrack, even before I settle in. I had never bet on horses before. I had never seen a horse race before, in fact. I go to the cashier to make my bet, and by the time I get back, the race is all over, and I hadn’t even had a chance to see the horses run.76Oral History, 195.

Upon arriving in New Orleans, Rawley lived in a small apartment on Bourbon Street, and threw himself both into his work and the rich social life available to a young, unmarried white professional at that time. He described the job in an interview with Kimberly Bird:

What was happening was that there was no work for anybody and the men couldn’t stand just sitting around at home without working, so they used to ride the freight cars to different cities. … There were maybe as many as a million men traveling on freight cars from city to city and it was demoralizing. They were demoralized. By the time they got to New Orleans when I was there, none of them really thought they could get work. They were demoralized, unshaven, they had lice, and the government had set up a kind of a camp for them. Well, it wasn’t really a camp. It was a facility, let’s say, on the other side of a river there. They were all sent there first to be deloused, to get a bath, probably to shave, and then they were sent into the city where our offices were, to talk and to get help from social workers. At that time, I was director of casework for the bureau. Actually, the job was too big for the staff. There weren’t nearly enough trained social workers to treat them all. So, I was fully trained by that time, but the people that came to work for us as social workers simply had a BA, it could be in any subject. The government was desperate to have a staff in place. You wound up with—I remember some of the staff members needed help themselves.77Oral History, 42-43.

After a year in this position, Rawley was invited to join the faculty at the Graduate School of Social Work at Tulane University, which was just beginning its program in social work (making it one of only two such programs in the whole country, along with Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland). Rawley taught courses in case work there for a year and enrolled as a graduate student in a number of additional social work courses at the school.

Return to New York City

Still restless, however, Rawley decided to return to New York City in 1935, and took an apartment on West 69th Street, near Broadway, just above a restaurant called Fleur du Lys, where he met and had occasional conversations with the composer Aaron Copland, who was then teaching at the New School for Social Research. With help from Judith Ephron, the wife of his old friend H.S. Ephron, he secured a position with the Jewish Family Service, a family counseling agency. Rawley remained in this job for five years, by far his longest stint to date in one position.

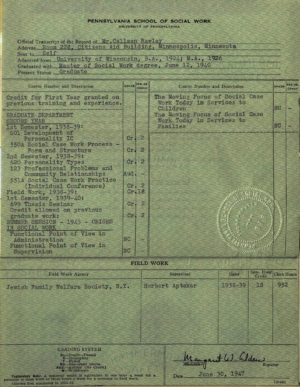

The culture at the Jewish Family Service at the time was characterized not only by a strong commitment to Freudian psychological principles, but by a widespread concern with improving the methodology of their practice and intensive, voluntary professional development, both of which appealed to the restless and inveterately curious Rawley. One of his coworkers, M. Robert Gomberg, began pioneering the practice of family therapy at this time, and Rawley recalled that “there were three of us in that office who’d … stay after hours to make the most detailed recording of everything that happened during an interview, and then examine it afterwards and talk about it.”78Oral History, 195. It was in this open, questioning professional environment that Rawley spent a brief internship in psychotherapy at the Lebanon Hospital Mental Health Clinic in the Bronx and underwent psychoanalysis himself for the first time. Most significantly, however, Rawley began yet another graduate program, commuting twice a week to Philadelphia for several years to pursue a Master’s degree in Social Work at the University of Pennsylvania, eventually earning his degree in 1940.

While the Jewish Family Service was dominated by Freudians, the social work program at Pennsylvania was directed at that time by Jessie Taft and Virginia Robinson, both of whom had been strongly influenced by the psychologist Otto Rank. Rawley admired Taft and Robertson a great deal, and became dedicated for the rest of his career to the pragmatic “functional” approach Taft and Robinson had championed in place a Freudian “diagnostic” approach, particularly in regards to his own psychotherapeutic practice. For Rawley, respect for the capabilities and autonomy of the patient were Rank’s great contribution to the field, he identified these values as the bedrock of his own orientation to psychotherapy: