Carl Rakosi’s Publishing History

Pre-‘Objectivist’ Poetry

While he first became interested in reading literature during his youth in Kenosha, Wisconsin, Carl Rakosi first began to write poetry as a sixteen-year-old freshman at the University of Chicago. During the winter quarter of his first and only year at Chicago, Rakosi took an Introduction to English literature course taught by Robert Morss Lovett. In this course, Rakosi befriended two fellow students who inspired and encouraged Rakosi in writing his own verse: George Schuyler, a young African-American man and aspiring writer, and an older Japanese man who wrote short, haiku-like poems. He would later recall, “One day I was a reader of literature and the next day, there was the knowledge, as if it had always been there, that I wanted to be a writer and that I could best express myself in poetry, not prose.”1”Autobiography,” 202.

Following his transfer to the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1921, Rakosi continued to develop his own sense of identity as a poet, majoring in English, reading a number of radical modernist literary magazines, and participating actively in literary societies on campus. Rakosi’s early work was heavily influenced by the Irish poet William Butler Yeats and the American writer Wallace Stevens. Rakosi later admitted “at first I was seduced by the elegance of language, the imaginative association of words; I was involved in a language world — a little like the world of Wallace Stevens, who was an idol of mine during a certain period.”2”Carl Rakosi,” Contemporary Literature 10.2 (Spring 1969), 182.

Rakosi was nineteen years old when he published his first poems in the Wisconsin Literary Magazine, a student publication for which he served as an editor along with his close friend Kenneth Fearing.3Fearing was the editor-in-chief of the magazine until he was forced to resign in March 1924 by a panel of faculty unhappy with his editorial tone. Rakosi published a total of seven poems here in 1923, with work appearing in the March, April, October, November, and December issues of the magazine. In May 1923, his poem “Gigantic Walker” appeared in The Liberator, a socialist magazine (and organ of the Communist Party of America), then edited by Robert Minor. In 1924, Rakosi published a poem in The Daily Cardinal, a University of Wisconsin-Madison newspaper, as well as two poems in Palms, a literary magazine being published from Guadalajara, Mexico by 22 year-old UC-Berkeley graduate Idella Purnell.

Rakosi’s first major literary success came in 1925, shortly after moving to New York City. The novelist Margery Latimer, Rakosi’s friend at the University of Wisconsin, had encouraged Rakosi to visit Jane Heap, the well-known editor of The Little Review, at the magazine’s Greenwich Village offices. Rakosi did so, and when with great trepidation he presented her with a manuscript of his poems, she agreed on first sight to publish his work. True to her word, three of Rakosi’s poems: “Sittingroom by Patinka,” “The January of a Gnat,” and “Flora and the Ogre,” appeared in the Spring 1925 issue of The Little Review, marking Rakosi’s first publication in a national literary magazine. Rakosi, then twenty-one years old, was elated. Later that year, after returning to Madison for graduate school, he published “The Bonds of Love,” a cynical poem about marriage, in The Nation, a well-known progressive weekly magazine. He also founded The Issue, a short-lived satirical magazine with Alexander Schindler, a Swiss medical student, publishing one of his own poems in the first issue and his translation of a poem by French surrealist poet and Communist fellow traveler Louis Aragon in the second (and final) issue of the magazine.

In 1926, Rakosi published poems in The Echo, The Nation, Two Worlds (a magazine edited by Samuel Roth), and Mike Gold’s newly founded Marxist magazine The New Masses. In 1927, Ezra Pound included four of Rakosi’s poems in the second issue of The Exile (though Rakosi did not know Pound had printed him until Louis Zukofsky wrote him a few years later), and a poem was chosen for inclusion in the first The American Caravan anthology, edited by Van Wyck Brooks, Alfred Kreymborg, Lewis Mumford, and Paul Rosenfeld. In 1928, Rakosi published two poems in Eugene Jolas and Maria McDonald’s Paris-based literary journal transition (the issue Rakosi appeared in was the final issue edited by Elliot Paul), and had a poem printed in the final issue of Pound’s The Exile.

“Objectivists” 1931 and the Immediate Aftermath

By the time that Zukofsky wrote to Rakosi late in 1930 with an introduction from Ezra Pound and a request for any unpublished poetry he might have for an issue of Poetry that Zukofsky was editing, it had been almost five years since Rakosi had published poetry in an American magazine of any kind, and more than two years since his last poems had appeared in print. Rakosi was then living in Houston, teaching high school English and mostly hating it, wondering how much longer he could hang on to writing poems and wondering what to do with his life.

For Zukofsky, however, Rakosi would have been one of the biggest names available to him, since he had previously appeared in some of the leading experimental and avant-garde publications of the day. Zukofsky’s letters and encouragement buoyed Rakosi considerably, and Zukofsky printed four of Rakosi’s poems, “Orphean Lost,” “Fluteplayers from Finmarken,” “Unswerving Marine,” and “Before You,” for the February 1931 “Objectivists” issue. No other poet had as many poems published in the issue, and Zukofsky further demonstrated his esteem for Rakosi’s work by giving it pride of place, publishing his four poems as the magazine’s opening content, gathered under a heading of “Before You.”

Rakosi’s appearance in Poetry and correspondence with Zukofsky spurred a burst of poetic productivity, and he published several additional poems in the remainder of the year, with work in three separate issues of Richard Johns’ magazine Pagany, an additional five poems selected by Harriet Monroe for the November 1931 issue of Poetry, and his sequence “A Journey Away” appearing in the Winter 1931 issue of Hound & Horn. In 1932, the Oppens published the Zukofsky-edited An “Objectivists” Anthology from Le Beausset, France, which included two new poems from Rakosi, and he published in the final issue of William Carlos Williams and Nathanael West’s revival of Contact and the first issue of The Lion and the Crown, a periodical edited by James G. Leippert at Columbia University. In 1933 and the first part of 1934, Rakosi continued actively publishing, with five poems appearing in the first two issues of The Windsor Quarterly, a poem in both the April and November issues of Poetry, and three poems in two issues of The New Act, an experimental literary review edited by Harold Rosenberg. Following his publication of two poems in the Spring 1934 issue of the The New Act, however, Rakosi stopped publishing poems in literary magazines, and returned to New York City the following year, devoting himself to a career as a professional social worker.

First Book

Though he had not published any new poems in literary magazines or journals for several years, Rakosi wrote to James Laughlin in October 1940, to inquire about the possibility of publishing a book with New Directions. Laughlin indicated that the press was just beginning a “Poet of the Month” series of chapbooks on a subscription model and offered him a place in that series. Rakosi accepted the offer, and after additional correspondence between the two men, a slim paperback of Rakosi’s poetry, entitled Selected Poems, was published in December 1941 as a poet of the month selection.

Cover of Carl Rakosi’s Selected Poems

Selected Poems

Selected Poems contained thirty four poems, twenty-five of which had already been published in various literary magazines or anthologies in the early 1930s, though often with different titles and considerable textual variation, as well as nine previously unpublished poems. The book was designed by Alvin Lustig and featured one of the first cover designs he made for New Directions. The jacket copy asserted:

Though he has been writing for some years, Rakosi has far too modestly allowed his light to be hidden under a bushel. An occasional magazine publication and some association with the “Objectivist” group in the early Thirties have been his only concessions to his admirers. But at last we have persuaded him to issue a selection of his work and this booklet is the happy result.

When its publication passed with little notice and Rakosi failed to obtain a Guggenheim grant in support of his proposed study of the psychology of the poet, Rakosi abandoned reading and writing poetry entirely. This break was more final than earlier equivocations, and following this break with writing, Rakosi devoted himself wholly to family life (he was married with two young children) and a career as a social worker and family therapist conducted under his legal name Callman Rawley, which he had assumed in 1925. The poet Carl Rakosi was, for all intents and purposes, dead.

Andrew Crozier and Rakosi’s Return to Poetry

In 1965, shortly before his planned retirement from as the long-time director of the Jewish Family and Children’s Service in Minneapolis, Callman Rawley received a wholly unexpected letter from Andrew Crozier, a young English poet studying on a Fulbright scholarship with Charles Olson at the State University of New York-Buffalo. Crozier’s letter read:

Please excuse me if I make any intrusion upon your privacy but I would like to write to you about the poems you published under the name Carl Rakosi. I have your address from the Hennepin County Welfare Department, to which I wrote at the suggestion of Charles Reznikoff in New York.

I have been interested in your poems since I saw your name mentioned by Kenneth Rexroth some three years ago [probably in Rexroth’s book, Assays, where he compares Rakosi to the French poet Pierre Reverdy], but until I came here last autumn was only able to turn up “A Journey Away” printed in Hound and Horn. I have now been able to find about eighty poems of yours, published between 1924 and 1934, and what immediately strikes me is the discrepancy between that body of work and your Selected Poems. And the way, say, long poems like “The Beasts” and “A Journey Away” are chopped up into smaller units in that volume.

I wonder, too, why you have stopped publishing since 1941 and whether you have been writing since then or not.

Again, please excuse me if this letter is an impertinence, but I like and admire your poems very much and feel impelled to write to you now, my interest is so engaged with them.4Source needed.

Rakosi recalled that upon reading Crozier’s letter:

My heart gave a leap. Something was moving in my distant young past. I began to feel slightly nervous. . . . This not at all unusual letter knocked the wind out of me. I sat there, I don’t know how long, not thinking anything, yet sensing that something big had just happened, something had changed. Was it possible I could write again? This time it was possible. I would be free in two years, and with great joy I started. The first poem I wrote was “Lying in Bed on a Summer Morning.” The old ticker was still there.5”An Interview with Carl Rakosi,” Conjunctions 11 (1988), 236.

After a nearly twenty-five year hiatus, the poet Carl Rakosi had been revived.

New Directions: Amulet and Ere-voice

Following this startling reawakening, Rakosi spent much of the next two years re-immersing himself in poetry, as both a reader and as a maker. He told George Evans and August Kleinzahler in 1988 that

Crozier’s letter had opened the door to my past and a kind of delirious excitement took hold of me at the realization that for the first time in my adult life I would shortly be altogether free of obstructions and distractions…no job, children all grown, no financial problems to worry about. But how to begin? There was no poetic impulse yet, and when it did begin to come, bit by bit, and I began to put words to paper, I felt an enormous uncertainty as to whether there was any poetry in me, and what would it be, and would it be good enough, that is, as good as my past work. In fact, when I sent Laughlin the manuscript of Amulet, that was what I said to him, I didn’t know whether I had all my old marbles. When it came down to the actual doing, the only hard problem I had, and that was discouraging, was getting back my old language. I was afraid that was gone for good after years of talking and writing nothing but the abominable language of sociology, the language of generalities and the impersonal, and of psychology. I had to undo a lifetime of linguistic habit and expunge it word by word out of my system.6”An Interview with Carl Rakosi,” Conjunctions 11 (1988), 239-240.

After a few months of active writing, Rakosi began to send out feelers regarding publication, writing first to James Laughlin, whose New Directions publishing company had published his Selected Poems and who was then contributing to the recovery of the Objectivists by publishing books by George Oppen and Charles Reznikoff. On October 18, 1965 Laughlin wrote to Rakosi: “I can’t publish, but will show it June Degnan, our co-publisher, who does books under the joint San Francisco Review-New Directions imprint.” Laughlin wrote Rakosi again in November 1965 and February 1966, declining to publish his book but encouraging Rakosi to seek out Degnan, referencing Charles Reznikoff and Kenneth Rexroth, and suggesting that the poet Denise Levertov might be a good choice for an introduction (she did in fact end up writing the book’s back jacket blurb). Laughlin ultimately changed his mind, however, and New Directions published Amulet in 1967.

Cover of paperback edition of Rakosi’s Amulet

Amulet

Amulet was designed by David Ford and featured a close up detail from a Union Carbide Corporation photograph printed in brilliant blue and red tones on the hardcover dust jacket and in gray scale on the paperback. The book was dedicated “To Andrew Crozier, who wrote the letter / which started me writing again, / And to my family. / L’hayim! Each of them came along just in time” and featured a back cover blurb from Denise Levertov which identified the book as a “selection from his poems, old and new,” briefly told the story of his abandonment and return to writing poetry, and identified Rakosi as a writer who “was well known in the Thirties, a leading member of the Objectivist Group, which also included William Carlos Williams, Louis Zukofsky, Charles Reznikoff, and George Oppen.”7Amulet, viii, n.p.

In the volume’s acknowledgements, Rakosi noted that

The poems in this volume written prior to 1939, in somewhat different form usually, made their appearance first in exciting little magazines of that day [followed by a list of magazine and anthology titles].

Recently The Paris Review reprinted “The Founding of New Hampshire” and “The Lobster.” I hope this means that the second generation finds those years a good vintage.

I did not write again until April 1965. Some of this new work has appeared in Poetry, The Massachusetts Review, and The Quarterly Review of Literature.8Amulet, iv.

Apart from this notice, however, the material was not arranged in any chronological order and there was no additional distinction made for the reader between old and newer work. Among the most notable of the new poems were the first five of Rakosi’s “Americana” poems, a sequence of typically short, ironic lyrics that often employed found language or vernacular speech and which illuminated some aspect of the peculiarly American character which Rakosi would continue to add to for decades to come.

Following the publication of Amulet, Rakosi was invited by L.S. Dembo to visit the University of Wisconsin-Madison in the spring of 1968, where he gave a reading and was interviewed for an issue of Contemporary Literature that Dembo was preparing on the Objectivist poets.9That interview was printed as part of the “The ‘Objectivist’ Poet: Four Interviews:” Contemporary Literature 10.2 (Spring 1969): 155-219, and has been reproduced courtesy of the University of Wisconsin Press. In December 1968, he retired from social work and psychotherapy, marking the end of Callman Rawley’s professional career. Upon his retirement, he essentially reverted to being Carl Rakosi, as his identity as a poet and writer became his most important public role for the remainder of his life (though his book’s copyright notices continued to be registered by Callman Rawley, which remained his legal name until his death). Following the publication of his interview with Dembo in the Spring 1969 edition of Contemporary Literature, Rakosi spent the 1969-1970 academic year as Writer-in-Residence at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Cover of Rakosi’s Ere-voice

Ere-Voice

Rakosi’s next book, Ere-Voice, was published by New Directions in 1971, with a Jean-Philippe Blaise photograph of a drawing by Argentinian painter and architect Miguel Ocampo as its cover. In the acknowledgments to the book Rakosi notes a special debt to Yaddo, the summer artist’s retreat in Saratoga Springs, “where most of these poems were written. I wish there were a catwalk from them to my dear family and friends.” Rakosi had first attended Yaddo in the summer of 1968, just after publishing Amulet, and went each summer from 1968-1975. The unsigned jacket copy claims that in this collection, Rakosi “again probes the minutiae of everyday experience … [but] now addresses itself with greater frequency to public issues,” and positioned Rakosi as “a leading member of the Objectivist Group.” The jacket also included Rakosi’s claim that his primary poetic intention is “to present objects in their most essential reality and to make of each poem an object … the opposite, in other words, of all forms of personal vagueness; of loose bowels and streaming, sometimes screaming, consciousness.”

Ere-Voice featured work which had previously been published in a dozen small magazines or anthologies in the United States and England, including The Nation, Clayton Eshleman’s Caterpillar, Sonia Raiziss’ Chelsea, the Zionist literary journal Midstream (where Charles Reznikoff’s wife Marie Syrkin served on the editorial board), Tim Longville and John Riley’s Grosseteste Review, and Dan Gerber and Jim Harrison’s Sumac. After Ere-Voice and Amulet sold poorly, New Directions dropped Rakosi from their list of authors (as they had done with Reznikoff), leaving Rakosi to find another publisher for any future manuscripts.

Ex Cranium, Night through Spiritus, I

Casting about in search of a new publisher, Rakosi turned to John Martin’s Black Sparrow Press, which had published a large collection of his friend and fellow “Objectivist” Charles Reznikoff’s work in 1974 under the title By the Well of Living & Seeing: New and Selected Poems.

Cover of Rakosi’s Ex Cranium, Night

Ex Cranium, Night

In 1975, Black Sparrow published Rakosi’s Ex Cranium, Night, a longer book that combined several poetic sequences (“Xanadu,” “Night,” “Americana” 22-34, “The Poet”) with a smattering of prose (largely aphoristic selections or statements of poetics under the section titles “Day Book,” “Ex Cranium, the Poet,” and “Observations,” as well as “The Artist,” which was structured as one side of an epistolary exchange from a fictional female painter based on an artist friend from Yaddo). Individual pieces collected in the book had appeared in two dozen literary magazines or journals, including a half-dozen in England or Australia. The book was dedicated “With love / to Leah / George Leanna Barbara / Jennifer Julie Joanna Miriam” and was produced in a typically attractive Black Sparrow fashion, featuring a two-toned letter-press cover and design by Barbara Martin. Two-hundred numbered and signed copies of the hardcover edition were produced, along with 26 handbound copies each containing an original holograph poem by Rakosi. A single-page biography at the conclusion of the volume gave a detailed and accurate account of his life, stating simply that “In the early 1930s he was associated briefly with the Objectivists.”10Ex Cranium, Night, 177.

Cover of Rakosi’s History: A Sequence of Poems

History: A Sequence of Poems

In 1981, Rakosi published two small chapbooks: History: A Sequence of Poems and Droles de Journal. History, published in London by Ian Robinson’s Oasis Books, contained a brief foreword by Rakosi, which read:

Over the years I have written poems having to do with the sense of the times in the 1920s and 1930s, but I didn’t realize until much later that they belonged together and that, with some later poems, what I had been writing about was history. Hence the title.

This new entity has six sections: a meditation, The Third Decade, The Fourth Decade, The Seventh Decade, The Eighth Decade, and an epilogue. In the third and fourth decades I was reporting on an “American character.” After that I could not find it. This bears out my experience in trying to teach John Berryman’s seminar, The American Character, at the University of Minnesota after his suicide. I found that until World War II there did seem to be an American character at work. After that we became more like the rest of the world …. split into fragments, diffuse, varied, a state on which the media feeds and constantly sounds the alarm, thereby inflaming the symptom and confirming the disintegration. The poet however will not go along.

I wonder myself now why HISTORY contains so few metaphors. I don’t think it was only because the content was sufficient without them, that it could speak for itself. I think it was also that I refrained from using the transforming power of the metaphor and the imagination because of my respect for the singular gravity and trauma of what was happening in the world.11History, 6.

Cover of Rakosi’s Droles de Journal

Droles de Journal

Droles de Journal was published by Allan and Cinda Kornblum’s The Toothpaste Press in West Branch, Iowa. The book was designed and printed by Allan Kornblum, handset by Ellen Weis, and bound by Rebecca Henderson in February 1981. The text itself was comprised of twenty numbered poems (most of which were brief and very witty) printed in an artist’s edition of 150 numbered and signed hardcover copies and 1500 paperback copies. Apart from excerpts from a glowing review of Rakosi’s work in Bookletter by the novelist Paul Auster printed on the back cover, the book contained no additional prefatory or biographical material.

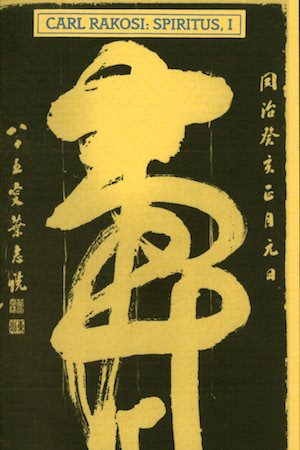

Cover of Rakosi’s Spiritus, I

Spiritus, I

In 1983, Ric and Ann Caddel’s Pig Press (operated out of Durham, England) published Spiritus, I, a slim (54 pages), handsome volume whose cover features a reproduction of a Ch’ing Dynasty rubbing of the Chinese calligraphic form of the character 壽 [shòu, long-life]. The book was divided into four numbered sections, beginning with a series of nine poems Rakosi called ‘meditations’; a second section which included both new work and reworkings of poems published in previous books: “Lying in Bed on a Summer Morning” (the first poem he wrote after receiving Andrew Crozier’s letter) and “Yaddo” (a composite of poems published in Ere-voice and Ex Cranium, Night); a third section with poems about urban life; and a short concluding section which contained two brief, witty poems. Poems in the book had previously appeared in nine different magazines, including Bradford Morrow’s Conjunctions, Eliot Weinberger’s Montemora, Cid Corman’s Origin, and Clayton Eshleman’s Sulfur. Rakosi dedicated the book to “Margery Latimer / Dearest of My Old Friends” and the back cover contained an excerpt from a 1942 letter from Wallace Stevens claiming that Rakosi’s excitement for “real things” meant that he possessed “exactly the kind of mind that appears to be required in contemporary poetry.”12Stevens had written Rakosi this letter in connection to his aborted application for a Guggenheim grant to study the psychology of the poet.

Collected Poems and Prose

The next Rakosi books to appear were collections of prose and of poetry that Rakosi had initially hoped would be significant events in establishing and developing his reputation, but which he ended up feeling mainly exasperated and very disappointed by. The National Poetry Foundation, an organization centered at the University of Maine, Orono and dedicated to convening conferences and publishing scholarship about poetry written in the Poundian tradition, agreed to publish two Rakosi volumes, one of collected prose, and the other of collected poems. Unfortunately for Rakosi, while Carroll Terrell was a well-liked academic, he was not a particularly effective publisher or marketer, and Rakosi found himself increasingly frustrated by his communications with Terrell regarding his forthcoming books. The first of the books to appear was The Collected Prose of Carl Rakosi, published in 1983, followed three years later by The Collected Poems of Carl Rakosi.

Cover of The Collected Prose of Carl Rakosi

The Collected Prose of Carl Rakosi

Rakosi’s Collected Prose, a slim book of less than 150 pages, bore a similar dedication as the one which had appeared in Spiritus, I: “To Margery Latimer / Dearest Friend of My Youth.” The book contained an illuminating twenty-page critical postscript by Burton Hatlen as well as a very brief foreword in which Rakosi explained:

Ordinarily, therefore, I avoid prose, for there is nothing I like better than to escape into a metaphor. But I am also ironic and like to romp, and occasionally, therefore, write prose, which I strive, against my nature, to make atomic and as hard and tight and natural as a hickory nut.13The Collected Prose of Carl Rakosi, 11.

The Collected Prose itself consists of seven pieces of varying lengths: “Day Book,” a revised and extended version of the prose passage of the same name which had appeared in Ex Cranium, Night; “My Experiences in Parnassus,” a short, satirical account of how to achieve fame as a poet; “The Artist,” a fictional epistolary story which had previously appeared in Ex Cranium, Night; “The Ordeal of Moses,” a brief satire about the nature of ‘Jewish’ art; “Observations,” a collection of aphorisms and meditations on life, art and identity; “Scenes from My Life,” a collection of nine autobiographical vignettes addressing his relationships with his parents, his college friendships with Margery Latimer, Kenneth Fearing, and Leon Serabian, Louis Zukofsky and the “Objectivist” label, Eugene McCarthy, Marya Zaturenska, Jorge Luis Borges, George Oppen, and Robert Duncan; and “Little Meditations,” another collection of meditative aphorisms.

Cover of The Collected Poems of Carl Rakosi

The Collected Poems of Carl Rakosi

Despite its title, The Collected Poems of Carl Rakosi was not a scholarly edited collection of Rakosi’s complete poetic output, but rather, a substantial selection (the book ran to nearly 500 pages) of Rakosi’s life work to that point, selected, revised, and arranged by Rakosi himself. Apart from the poems, a dedication: “To Leah / Dear Wife / Cantus Firmus” and an index of first lines, the book includes only a very succinct foreword in which Rakosi informed the reader that:

This book has not been put together with the poems in chronological sequence. That would have been useful to scholars interested in tracing my development as a poet, but I have no such interest, and even if I had, I did not have the time and the energy to research all the publication dates (I kept no dates of composition), although my perceptive and painstaking friend, Andrew Crozier, assures me that he has them for my early poems, along with the changes I made in them over the years from one published version to another. Had I had more inclination, I suspect that even with this in hand I might still have been reluctant because the presumption underlying chronological sequence is that a literary development and some kind of psychological progression or evolving take place in this way. They may or may not. To the extent that they do, they can only be partial because a poet in the course of his life makes repeated leaps ahead and unwanted reversions, the reasons for which can only be speculated on at great risk, even by him, since he does not make them on purpose or for a purpose (that he is aware of). In any case, a chronological variorum is still possible at another time and by another person.

I have, as I said, chosen a different course. It seemed to me more creative and interesting to organize the poems as if I were making up a book for the first time, with the parts before me, the individual poems. And I followed the logic of that. A gamble, I know, because they are not, after all, a book in the sense of composition. On the other hand, neither are they just an aggregation. What I think they are, the larger and perhaps different meaning they have when viewed in this way, is to be found, when it is there, in the arrangement. What will not be found is the coherence of a composition, but coherence these days has larger parameters and tolerances, and perhaps the gamble will pay off. In other words, the reader gets not a file of my previous volumes, AMULET plus ERE-VOICE plus EX CRANIUM, NIGHT plus HISTORY plus SPIRITUS, I, but an as-if-book, with no obvious connection between the AMERICANA and the DROLES DE JOURNAL and the other parts. The reader who is bothered by this can view them as separate books. Even as such, they seem to me to be better integrated and more coherent than the original volumes. At least they are different.14The Collected Poems of Carl Rakosi, 17-18.

These collected volumes were not received very well, either by critics or by reviewers (a large part of Rakosi’s frustration with Terrell as his publisher was his inability to get the books distributed properly or sent in a timely fashion to the list of willing reviewers he had prepared for Terrell), and Rakosi ended up feeling angry about the publishing experience he had with NPF. It would be nearly a decade before Rakosi’s next book appeared in print, and eleven years before he would publish new work in book form.

Cover of Rakosi’s Poems 1923-1941, edited by Andrew Crozier

Poems 1923-1941

The careful reader will notice that Rakosi’s foreword to the Collected Poems both allowed for the possibility of a “chronological variorum … at another time and by another person” and referenced the “perceptive and painstaking” work that had already been done at that time on Rakosi’s earliest poems by Andrew Crozier. In 1995, Douglas Messerli’s Sun & Moon Press published precisely the kind of book Rakosi had suggested might be undertaken by some future scholar in the form of Poems 1923-1941, Crozier’s superbly edited collection of Rakosi’s early writing.

Poems 1923-1941 included two pieces of introductory prose. The first of these is “A Cautionary Note to the Reader from the Author,” in which Rakosi reflected on the atmosphere of literary posturing endemic to the era in which the earliest poems were produced, discussed his ideas of poetic sincerity, asked for the reader’s forbearance with his earliest work, noting with dismay the heavy Christological references in his earliest poems, and concluded with his belief that once published, poems “stand there as givens,” since publication severs the relationship between an author and his poem such that each poem “can be said to speak for itself and the matter is strictly between it and the reader.”15Poems 1923-1941, 8-9. The second is Crozier’s editorial introduction, the main section of which is titled “Found: A Modern Masterpiece.” Here, Crozier’s stated his belief that this text “will significantly extend our knowledge of the repertoire of modernism and our historical understanding of the ‘Objectivists'” and made plain his intention to allow readers to both “attach Rakosi to the real historical past of modernism, and to reread the later Rakosi who has … been able to keep his text freely at his disposal as its own creative resource.”16Poems 1923-1941, 13.

The collection itself included all of the poems Rakosi published from 1923-1941 that Crozier succeeded in locating (presented in chronological order and with textual variants and publication details given in the notes), as well as more than 30 pages of unpublished, never completed, and revised poems from this period of Rakosi’s career.

Last Books

Though Rakosi continued writing and publishing poems in literary magazines across the English-speaking world following the appearance of his Collected Poems in 1986, his next book of new material did not appear for more than a decade, when his collection The Earth Suite was published by Nicholas Johnson’s etruscan books out of South Devonshire, England in 1997.

Cover of Rakosi’s The Earth Suite

The Earth Suite

The Earth Suite was dedicated “For Marilyn Kane / dear companion / and much more” and included roughly fifty pages of new poems, as well as a cover image and ten drawings by Basil King, an English artist and poet who has lived in Brooklyn since 1968. The poems were preceded by two short prose pieces: a short foreword from Robert Creeley praising Rakosi’s honesty, clarity, and quality, and an introduction by Andrew Crozier. The Earth Suite was printed in both paper and cloth editions, of which twenty copies were signed by both Rakosi and Basil King, and an additional fifteen copies contained additional holograph material by Rakosi.

Cover of Rakosi’s The Old Poet’s Tale

The Old Poet’s Tale

With Andrew Crozier’s Poems 1923-1941 having established a carefully annotated, critically edited, chronologically presented collection of Rakosi’s early work, there remained the task of collecting and presenting his post-1965 output, particularly since The Collected Poems did not match the traditional scholarly definition of the term. It appears that Nicholas Johnson and Andrew Crozier intended to remedy that situation by printing a series of Rakosi’s collected works. The first of these, announced on the back jacket as “Collected Works Volume 1” was The Old Poet’s Tale, published in 1999 in an edition of 700 paperbound and 100 casebound copies, of which the first 26 were lettered with additional holograph material by Rakosi. The Old Poet’s Tale was dedicated “For Andrew Crozier” and featured more than 250 pages of new poetry, divided into six sections: “In the Constellation”; “The Old Poet’s Tale” (named for a poem of the same title, a twenty page elegy for George Oppen); “Meditations”; “Satyricon”; “Droles de Journal (1924 – “; and “Poet’s Corner,” which concluded with “Reflections on My Medium,” a six-page prose reflection touching on music, form, and abstraction.

The book’s back matter also contained a small notice inviting anyone who “would like to further assist the project for Carl Rakosi’s Collected Works” to “please contact the publishers.” While Johnson and Andrew Crozier intended to oversee further volumes in the series, Rakosi was unable, despite several drafts, to arrange a completed manuscript order for the second volume before his death in 2004. Andrew Crozier, perhaps Rakosi’s greatest champion, died in 2008, and the work of producing a critically-edited collected Rakosi which spans the last four decades of his career remains unaccomplished.

Timeline

Poetry

Selected Poems, Norfolk, Connecticut: New Directions, 1941. Library.

Selected Poems, Norfolk, Connecticut: New Directions, 1941. Library. Amulet. New York: New Directions, 1967. Library.

Amulet. New York: New Directions, 1967. Library. Ere-voice. New York: New Directions, 1971. Library | Publisher.

Ere-voice. New York: New Directions, 1971. Library | Publisher. Ex cranium, night. Los Angeles: Black Sparrow Press, 1975. Library.

Ex cranium, night. Los Angeles: Black Sparrow Press, 1975. Library. History: A Sequence of Poems, London: Oasis, 1981. Library.

History: A Sequence of Poems, London: Oasis, 1981. Library. Droles de journal, West Branch, Iowa: Toothpaste Press, 1981. Library.

Droles de journal, West Branch, Iowa: Toothpaste Press, 1981. Library. Spiritus, I, Durham, N.C.: Pig Press, 1983. Library.

Spiritus, I, Durham, N.C.: Pig Press, 1983. Library. The Collected Poems of Carl Rakosi, Orono, Maine: National Poetry Foundation, 1986. Library | Publisher.

The Collected Poems of Carl Rakosi, Orono, Maine: National Poetry Foundation, 1986. Library | Publisher. Poems, 1923-1941. Ed. Andrew Crozier. Los Angeles: Sun & Moon Press, 1995. Library.

Poems, 1923-1941. Ed. Andrew Crozier. Los Angeles: Sun & Moon Press, 1995. Library. The Earth Suite, Buckfastleigh, England: Etruscan Books, 1997. Library | Publisher.

The Earth Suite, Buckfastleigh, England: Etruscan Books, 1997. Library | Publisher. The Old Poet’s Tale, Buckfastleigh, England: Etruscan Books, 1999. Library | Publisher.

The Old Poet’s Tale, Buckfastleigh, England: Etruscan Books, 1999. Library | Publisher.

Prose

The Collected Prose of Carl Rakosi, Orono, Maine: National Poetry Foundation, 1983. Library | Publisher.

The Collected Prose of Carl Rakosi, Orono, Maine: National Poetry Foundation, 1983. Library | Publisher.

References

| ↑1 | ”Autobiography,” 202. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | ”Carl Rakosi,” Contemporary Literature 10.2 (Spring 1969), 182. |

| ↑3 | Fearing was the editor-in-chief of the magazine until he was forced to resign in March 1924 by a panel of faculty unhappy with his editorial tone. |

| ↑4 | Source needed. |

| ↑5 | ”An Interview with Carl Rakosi,” Conjunctions 11 (1988), 236. |

| ↑6 | ”An Interview with Carl Rakosi,” Conjunctions 11 (1988), 239-240. |

| ↑7 | Amulet, viii, n.p. |

| ↑8 | Amulet, iv. |

| ↑9 | That interview was printed as part of the “The ‘Objectivist’ Poet: Four Interviews:” Contemporary Literature 10.2 (Spring 1969): 155-219, and has been reproduced courtesy of the University of Wisconsin Press. |

| ↑10 | Ex Cranium, Night, 177. |

| ↑11 | History, 6. |

| ↑12 | Stevens had written Rakosi this letter in connection to his aborted application for a Guggenheim grant to study the psychology of the poet. |

| ↑13 | The Collected Prose of Carl Rakosi, 11. |

| ↑14 | The Collected Poems of Carl Rakosi, 17-18. |

| ↑15 | Poems 1923-1941, 8-9. |

| ↑16 | Poems 1923-1941, 13. |