Who were the “Objectivists”?

In their simplest definition, the “Objectivists” were a group of thirty modernist writers gathered and presented by Louis Zukofsky in two explicitly-titled “Objectivist” publications: the February 1931 issue of Chicago’s Poetry magazine, and An “Objectivists” Anthology, published the following year in France. Beginning in the mid-1930s, many of the writers identified as “Objectivist” ceased writing poetry or faded into obscurity until the early 1960s, when several members of the group reemerged as active poets and enjoyed a surge of attention and retroactive identification as “Objectivists.”

Core “Objectivists”

The seven core “Objectivist” writers featured on this website: Louis Zukofsky, Charles Reznikoff, George Oppen, William Carlos Williams, Carl Rakosi, Basil Bunting and Lorine Niedecker, were connected through a shifting web of friendship and joint publication beginning in the mid-1920s and stretching into the early twenty-first century. All of these writers published important work after 1962, and of the seven, all but Lorine Niedecker appeared in both of the foundational “Objectivist” publications. I recognize that my decision to refer to Niedecker as an “Objectivist” poet despite her absence from the early “Objectivist” publishing ventures and group publications could be contested, so some justification for this decision may be helpful.1Jenny Penberthy and other attentive readers of Niedecker’s poetry have long noted her intellectual and poetic independence, including surrealist tendencies, of which Zukofsky did not approve, in both her earliest and latest poetry. See Penberthy in How2 and both Ruth Jennison and Rachel Blau DuPlessis’ contributions to Radical Vernacular (pp. 131-179). Niedecker became attracted to the group, and to Zukofsky in particular, after reading the February 1931 issue of Poetry in her local library. This encounter prompted Niedecker to write directly to Zukofsky sometime in mid-late 1931, and Niedecker’s first submission to Poetry magazine, dated November 5, 1931, mentions her having been encouraged to do so by Zukofsky.2That letter reads, in full: “Dear Miss Monroe, Mr. Zukofsky encourages me to send some of my poems to you to be considered for “Poetry”. Very truly yours, Lorine Niedecker.” Niedecker to Harriet Monroe in Poetry: A Magazine of Verse Records 1895-1961, Box 18, Folder 2, University of Chicago Special Collections. Niedecker’s first letter to Zukofsky marked the commencement of an intense, lifelong friendship, developed through frequent correspondence for nearly 40 years.3Niedecker and Zukofsky conducted one of the deepest, most fruitful, and longest lasting epistolary friendships among writers of which I know. They destroyed much of their correspondence, but a significant portion of the surviving letters from Niedecker were collected and edited by Jenny Penberthy in Niedecker and the Correspondence with Zukofsky 1931–1970, published in 1993 by Cambridge University Press. Fragments of Zukofsky’s side of the correspondence are held by the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin. Late in 1933, Niedecker traveled to New York City for an extended stay with Zukofsky, during which time she met Charles Reznikoff, George and Mary Oppen, and (probably) William Carlos Williams. In August 1934, Zukofsky wrote to T.C. Wilson, a young graduate student at the University of Michigan who was editing an issue of Bozart-Westminster along with Ezra Pound, indicating that he “[c]onsider[ed] it a grave error not to have included her in Objectivists Anthology, but she has travelled some since 1932.”4I am grateful to Jenny Penberthy for bringing this letter to my attention in September 2018. The rest of the letter is full of detailed, though qualified, praise for Niedecker, including the assertion that Niedecker was “the only woman in the U.S.A. as far as I know now writing poetry, with the exception of Marianne Moore – and promising more of a base to build on than Marianne. Suggest that you take something by her whether you like it or not, or whether E.P. [Ezra Pound] likes it or not — such exceptions should be made sometimes so as not to risk dogma.” Zukofsky’s letters to Wilson are held in the T.C. Wilson papers at Yale University. Later in life, Niedecker met both Carl Rakosi and Basil Bunting, who in particular had been a longtime admirer of her writing. While I would not go so far as Rakosi in describing Niedecker as the “most Objectivist of all of us,”5Quoted in Bird, 71 it is my view that Niedecker, by virtue of both her personal relationships with other members of the group and her poetic sensibilities, warrants inclusion among the core “Objectivists.” Two other writers, Robert McAlmon and Kenneth Rexroth, also appeared in both of the original “Objectivist” publications, but I have chosen to exclude them from my list of core “Objectivists,” and discuss the reasons for this decision at greater length below.

Speaking purely in terms of the lives of the core “Objectivists,” there are a number of biographical similarities. The group’s geographic center was New York City, and though all seven were never in the area at the same time, all core members either lived in the city or spent significant periods of time there between 1928 and 1935.6Apart from a stint at graduate school in Madison, Wisconsin during the 1930-1931 academic year and a trip to visit Pound and other artistic friends in Europe in the summer of 1933, Zukofsky spent the entirety of these years in New York City. Reznikoff lived in New York City for his entire life, apart from a year at journalism school in Missouri (the 1910-1911 academic year), a cross-country trip selling hats for his parents’ business and extended stay in Los Angeles from April-June of 1931, and a two year stint working in Hollywood for his friend Al Lewin (from March 1937 through June 1939). The Oppens arrived in New York City in 1928, living briefly in Greenwich Village before taking a room at the Madison Square Hotel (on the corner of Madison Avenue and 26th Street, near the north east corner of Madison Square Park) for the rest of the winter. They lived briefly with Zukofsky’s close friends Ted and Kate Hecht on Staten Island in the spring, before renting a small house in New Rochelle harbor, the city where George had been born. They returned to San Francisco at the end of the summer in 1929, and lived a rented house in Belvedere for a year before leaving for France in the summer of 1930 around the same time that Zukofsky left New York for Madison. The Oppens arrived in Le Havre, and stayed in France until early in 1933, when they left Paris to return to New York, taking an apartment in Brooklyn Heights near Zukofsky. The Oppens lived in New York from 1933 until the early 1940s, when they moved to Detroit. From 1913 until their deaths, Williams and his wife Flossie made their home some 25 miles northwest of Manhattan at 9 Ridge Road in Rutherford, New Jersey, from which location Williams made frequent visits to the city. Carl Rakosi lived in New York City from 1924 to 1925 and again from 1935 to 1940. Bunting lived in New York City for the last half of 1930: he and his first wife, Marian Culver, were married on Long Island on July 9, 1930 and lived in Brooklyn Heights through January 1931, when Bunting’s six-month visa expired and the couple returned to Rapallo, Italy. Although Zukofsky was in Madison during most of Bunting’s time in New York City, Bunting met Williams, René Taupin, and others in Zukofsky’s circle, and met Zukofsky in person when Zukofsky returned to the city for the winter holidays. Niedecker came to New York City for the first time in late 1933, and over the next several years would spend several months in the city, living with Zukofsky during her sometimes lengthy visits. Four of the group were Jewish,7Zukofsky, Reznikoff, Oppen, and Rakosi four were the children of American immigrants,8Zukofsky’s parents immigrated from what is now Lithuania, Reznikoff’s parents immigrated from Russia, Rakosi was born in Germany and immigrated from Hungary when he was six years old, and Williams’ parents had immigrated from Puerto Rico, though his father had been born in England. and they were generally non-academic; apart from Zukofsky, none held graduate degrees connected to literature or university affiliations of any kind until the 1960s, when some members of the group began to be invited to fill artist-in-residence positions at various American universities.9Zukofsky earned a master’s degree in English from Columbia University in June 1924, writing his thesis on the writings of the historian Henry Adams. In February 1946, he began a teaching position as an English instructor at the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn (now operating as the New York University Tandon School of Engineering), where he taught until his retirement in May 1965. Reznikoff attended journalism school for a year at the University of Missouri and considered pursuing a Ph.D. in history before enrolling in law school, earning his LLB from New York University in 1915 and being admitted to the bar the following year. Reznikoff took a few postgraduate courses in law, but never earned an advanced degree. Oppen dropped out of Oregon State Agricultural College (now Oregon State University) after he was suspended and Mary was expelled from school for their relationship. Neither George or Mary earned university degrees. Williams attended medical school at the University of Pennsylvania, where he befriended classmates Ezra Pound and Hilda Doolittle [H.D.], graduating in 1906 and filling internships at two New York hospitals and pursuing advanced study in pediatrics in Leipzig, Germany. Rakosi attended the University of Chicago for a year before transferring to the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in English in 1924 and a master’s degree in industrial psychology in 1925. Rakosi attended a wide range of graduate programs in the 1920s and 1930s, briefly enrolling in both the Ph.D. program in English literature and law school at the University of Texas at Austin and medical school at the University of Texas Medical Department in Galveston but leaving each program before earning a degree. After choosing a career as a social worker, Rakosi attended the Graduate School of Social Work at Tulane University in New Orleans and eventually earned his master’s degree in Social Work from the University of Pennsylvania in 1940. Between 1952 and 1954, he would complete course work in the Social Work Ph.D. program at the University of Minnesota, but he never completed the doctorate. Bunting was enrolled at the London School of Economic from October 1919 to April 1923, but was very casual in his studies and left without earning a degree. Niedecker attended Beloit College from 1922-1924, but family financial pressures forced her to leave without completing her degree. With the exception of Williams and Reznikoff, all were of the same ‘generation,’ having been born between 1900 and 1908.10Williams was born in Rutherford, New Jersey on September 17, 1883, and Reznikoff was born in New York City on August 31, 1894. Of the five born after the turn of the century, Basil Bunting was the eldest and George Oppen the youngest, with Niedecker, Rakosi, and Zukofsky having being born during the eight month span from May 1903 and January 1904.11Bunting was born on March 1, 1900 in Scotswood-on-Tyne, a western suburb of Newcastle, England; Niedecker was born on May 12, 1903 on Blackhawk Island near Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin; Rakosi was born on November 6, 1903 in Berlin, Germany; Zukofsky was born on January 23, 1904 in New York City; Oppen was born on April 24, 1908 in New Rochelle, New York. Not surprisingly, considering his seniority relative to the rest of the group, Williams was also the first of the “Objectivists” to die, in 1963, just as many of the writers who had been published with him as “Objectivists” were beginning to reemerge to greater public notice.12William Carlos Williams died March 4, 1963, aged 79; Lorine Niedecker died December 31, 1970, aged 67; Charles Reznikoff died January 22, 1976, aged 81; Louis Zukofsky died May 12, 1978, aged 74; George Oppen died July 7, 1984, aged 76; Basil Bunting died April 17, 1985, aged 85; Carl Rakosi died June 25, 2004, aged 100. For comparison, Ezra Pound was born on October 30, 1885 in Hailey, Idaho and died on November 1, 1972 in Venice, Italy, aged 87. The last surviving “Objectivist” was Rakosi, who published his final volume of poetry in 1999, and continued sending new work in magazines and giving interviews until shortly before his death, aged 100, on June 25, 2004.

In addition to their shared publication efforts, the “Objectivists” were also loosely united by shared political and poetic affinities. In contradistinction to Pound, Eliot, and Cummings, three of the most prominent American modernist poets of the era, each of the “Objectivists” was leftist in their politics, with each generally expressing Marxist, socialist, or Progressive sympathies.13Oppen and Rakosi were both members of the Communist Party of the United States of America in New York City during the last half of the 1930s, but neither remained an active member of the party by the end of the decade. Zukofsky appears to have applied for membership in the Communist Party in 1925, when his close friend Whittaker Chambers began to ingratiate himself with the party’s New York leadership, but others recalled that his application was rejected, though the influence of Marxist ideas on Zukofsky remained prominent in his poetry and private letters through the late 1930s and is clear in his editorial decisions, both in regards to who he selected for inclusion in the “Objectivist” publications and afterward. In 1934 and 1935, Zukofsky spent several months preparing A Worker’s Anthology (though never published, many of the poems he gathered for this manuscript made their way into his A Test of Poetry), joined the anti-fascist (and Communist-affiliated) League of American Writers and worked briefly as an unpaid poetry editor for the prominent Communist-affiliated literary magazine New Masses. He and Bunting both argued politics with the fascist-sympathizing Pound in their letters throughout the 30s, with Zukofsky taking up more Marxist-Leninist positions and Bunting more anarcho-socialist ones. In a July 1938 letter to Pound, Zukofsky wrote: “Can’t guess what Kulchah is about, but if you want to dedicate yr. book to a communist (me) and a British-conservative-antifascist-imperialist (Basil), I won’t sue you for libel and I suppose you know Basil. So dedicate” (Pound/Zukofsky, 195). Zukofsky’s multi-hybrid classification of Bunting is a good sign of the difficulty even his closest friends experienced in classifying his political views. Bunting attended a Quaker secondary school and was imprisoned as a conscientious objector during the first World War and for several years as a young adult was, like his father, a dues-paying Fabian Socialist. His mature political views, while largely uncategorizable, resemble something of a fusion between socialism and anarchism, though he was perhaps the most suspicious of ideology of the whole group, arguing strenuously for the separation of literature from both political and economic motives and ends. A flavor of his independent-mindedness comes through in a 1954 to Dorothy Pound: “our only hope for our children is to destroy uniformity, centralization, big states and big factories and give men a chance to vary and live without more interference than it is the nature of their neighbors to insist on” (quoted in Basil Bunting, 12). Williams’ politics might be best described as democratic populist, and Niedecker was sympathetic to both the strain of Progressivism led by Wisconsin politician Robert La Follette and Henry Wallace as well as the socialism of William Morris. For more on Niedecker’s politics, see: http://steelwagstaff.info/lorine-niedecker-and-the-99/. Reznikoff was the least overtly political of the group, though his writing is profoundly sympathetic to human suffering and what we would today refer to as social justice concerns. He did also work for seventeen years in an editorial capacity on the Labor Zionist journal Jewish Frontier alongside his more politically engaged wife Marie Syrkin, who was the daughter of Nahum and Bassnya Osnos, two prominent Socialist Zionists, as well as a close friend of the Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir. Their poetics might be described as sympathetically heterogeneous, with Ezra Pound and the imagist tradition serving as important common touchstones for the group.

The Formation of the “Objectivist” Core

If there was in fact an “Objectivist” core, comprised of Zukofsky, Reznikoff, Oppen, Williams, Rakosi, Bunting and Niedecker, several questions must be answered. Chief among them: How did these seven writers come to know each other? What were the particular threads of connection and aesthetic principles which united them? How and why were these links forged, maintained, and, in some cases, dissolved?

Zukofsky, Williams, Reznikoff, and the Oppens could be said to form something like the group’s original and most durable nucleus, with their connections beginning to form in 1928 and each of them having frequent contact with each other in or near New York City over the next half dozen years.14Zukofsky spent the 1930-1931 academic year teaching at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the Oppens lived in California and France for significant periods in the early 1930s, and Reznikoff took a cross-country trip selling hats for his parents’ business followed by extended stay in Los Angeles from April-June of 1931, but apart from these exceptions, all lived within 20 miles of each other in the New York metro area from 1928 through 1935. Zukofsky and Williams met in April 1928 at the encouragement of Ezra Pound, and Zukofsky met the Oppens later that same year at a party hosted by their mutual friends, the designers Russel and Mary Wright. It’s unclear exactly where and when Zukofsky and Reznikoff met, but Seamus Cooney has plausibly suggested that they met in 1928 at one of the Menorah Journal dinners hosted by its editor Henry Hurwitz. The earliest reference I’ve found to him in Zukofsky’s correspondence are a December 9, 1929 from Ezra Pound praising some “Reznikof prose” that Zukofsky had sent him as being “very good.”15Pound/Zukofsky, 26. Zukofsky’s prior letter also referenced Reznikoff’s having a printing press, which got Pound quite excited. In subsequent letters, Zukofsky clarified the situation and informed Pound of an upcoming meeting with Reznikoff in which he intended to “talk business” regarding the use of Reznikoff’s press, which he operated from his basement of his sister’s home upstate.

Basil Bunting lived in New York for several months in 1930 and 1931, during which time he established friendships with both Williams and Zukofsky. On July 11, 1930, two days after his marriage to Marian Culver on Long Island, Bunting sent Zukofsky a postcard that read, simply: “Dear Mr Zukofsky – Ezra Pound says I ought to look you up. May I?” Zukofsky assented and the two men quickly became friends, with Zukofsky spending time with Bunting while back in New York City during the winter holidays from his teaching position in Wisconsin. Williams also references having supper with Robert McAlmon, Basil Bunting and his American wife Marian in a January 15, 1931 letter to Zukofsky.16The Correspondence of William Carlos Williams and Louis Zukofsky, 77. Bunting would continue to correspond with both Zukofsky and Williams for several years.17See The Poem of a Life, 73-74 and A Strong Song Tows Us, 162-168 for more detailed accounts of the origin of Bunting and Zukofsky’s friendship. The Oppens, who were in France while Bunting and his wife were in New York, did however visit Rapallo in 1932, where they met both Ezra Pound and the Buntings, and they met again with Pound in Paris shortly before their return to the United States early in 1933.18The Oppens had financed the publication by TO, Publishers of a book consisting of two of Pound’s prose works and met with Pound in a Parisian café to inform him that they were discontinuing the press for financial reasons and would not print his ABC of Economics, as he had hoped. For Mary Oppen’s later account of their relationship with Pound and Bunting during this time, see her Meaning a Life, pp. 131-137. Rakosi was initially connected with the group solely through correspondence with Zukofsky, as he was living in Texas during the early 1930s and did not move back to New York City until 1935, by which time the Oppens and Zukofsky had broken their friendship and the Objectivist Press had essentially ceased operating as a collective publishing venture. While Rakosi and Zukofsky enjoyed rich social relations between 1935 and 1940, when both men lived in New York City, Rakosi was already drifting away from poetry and towards a long professional career as a social worker.19Rakosi stopped reading and writing verse entirely towards the end of his time in New York City. Rakosi, who had changed his name to Callman Rawley for professional reasons, earned his master’s degree in social work from the University of Pennsylvania and married Leah Jaffe in the spring of 1939. Following what he described as “a dreadful existential state, something grey and purposeless between living and dying, and so physical that for a while I was sure I was going to die” that came on when he realized that he was going to stop writing poetry, Rakosi took a job in Saint Louis in 1940 and “went on with my life as a social worker and therapist” (Autobiography in Contemporary Autobiography series, 208). For more on this period in Rakosi’s life, see http://theobjectivists.org/the-lives/carl-rakosi/. Niedecker began corresponding with Zukofsky shortly after reading the “Objectivists” issue of Poetry in her local library, and she first travelled to New York City late in 1933. Niedecker met Charles Reznikoff, the Oppens, and Williams while living with Zukofsky in New York City in the 30s, and both Rakosi and Bunting visited her at her home on Blackhawk Island in the late 1960s.20Carl Rakosi visited Lorine Niedecker and her husband Al Millen at their home on Blackhawk Island in March 1970 while he was serving at the Writer-in-Residence at UW-Madison, writing that “moment I walked in her door, she was opposite of recluse: outgoing, of good cheer, very lively. Time flew. Delightful afternoon” (Carl Rakosi Papers, Mandeville Special Collections, UCSD, MSS 355, Box 4, Folder 4). Though Bunting and Niedecker did not meet in person until June 1967, when Bunting and his daughters visited Niedecker at her Blackhawk Island home, they had known each other through correspondence, and for a short time Bunting had explored the possibility of going into the carp-seining business with Niedecker’s father Henry. Niedecker wrote to Cid Corman on June 15, 1966: “Basil Bunting–yes, I came close to meeting him when he was in this country in the 30’s. Some mention at the time of his going into the fishing business (he had yeoman muscles LZ said and arrived in New York with a sextant) with my father on our lake and river but it was the depression and at that particular time my dad felt it best to ‘lay low’ so far as starting fresh with new equipment was concerned and a new partner – the market had dropped so low for our carp – and I believe BB merely lived a few weeks with Louie without engaging in any business. He’s probably a very fine person and I’ve always enjoyed his poetry” (Faranda, “Between Your House and Mine“: The Letters of Lorine Niedecker to Cid Corman, 1960-1970, 88).

As this brief chronology of their meeting demonstrates, and as I argue in greater detail elsewhere on this site, the “Objectivists” 1931 issue of Poetry might be more properly considered a mid-point rather than the beginning of the group’s affiliation, serving as a public unveiling more than anything else.21The best extant resource which makes an effort to empirically document the pre-1931 “Objectivist” associations is Tom Sharp’s doctoral dissertation, “Objectivists” 1927-1934: A critical history of the work and association of Louis Zukofsky, William Carlos Williams, Charles Reznikoff, Carl Rakosi, Ezra Pound, and George Oppen, which he completed at Stanford University in 1982, and which includes a wealth of well-documented research on the extant correspondence between members of the “Objectivist” nexus in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Sharp did not pursue a career in academia and his dissertation remained unpublished until 2015, when he published large portions of it, at my urging, on his own website: http://sharpgiving.com/Objectivists/index.html. See Chapters 1, 9, and 11 especially. While Poetry marked their initial presentation, the main core of “Objectivists” had already been developing their own affinity and publication network, at least since 1928. Their shared publication history is traced in much greater detail in the “The Work” section of this site, but here I will detail their personal and biographical connections.

Imagining a Network Graph

There can be no disputing that Louis Zukofsky was the group’s central figure, as both the inventor of the group’s name and the editor who selected the writers and work presented publicly as “Objectivist” and provided the critical framing for the group and their context. As the intellectual, editorial, and in many respects energetic center of the group, Zukofsky was thickly connected to all of the other “Objectivists,” both core and peripheral. What is frequently less appreciated, however, was the significant, though less visible, role played in the formation and coherence of the group by the better established modernist poets William Carlos Williams and Ezra Pound.

To draw a graph of the Objectivist network as it existed in the late 20s-early 30s, one might first begin by representing Pound and Williams as two loosely-bound sibling roots, noting that their relationship with each other had predated the formation of the Zukofsky-led group by more than twenty-five years.22Pound, Williams, and Hilda Doolittle [H.D.] all met in Philadelphia in the early 1900s. Pound and Williams met in the fall of 1902, when both were enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania, where H.D.’s father was a professor of Astronomy. In 1903, Pound transferred to Hamilton College, but continued to see Williams during school breaks when he returned to his parents’ home in Wyncote, a Philadelphia suburb. In 1905, Pound returned to Penn to begin work on his master’s degree, and they resumed their friendship in earnest. Williams left Philadelphia in 1906 for a medical internship in New York City, and Pound took his ill-fated job teaching foreign languages at Wabash College in a small Indiana town in 1907 (he was fired in the spring of 1908 and left for Europe shortly thereafter). Pound dedicated his 1912 collection Ripostes to Williams and included Williams’ poem “Postlude” in his 1914 Des Imagistes anthology and his poems “In Harbor” and “The Wanderer” in his 1915 Catholic Anthology. He also wrote an introductory note to a selection of poems from Williams’ book The Tempers published in The Poetry Review in October 1912 and reviewed the book in The New Freewoman in December 1913. Though no letters from Williams to Pound written prior to 1921 have survived, they corresponded regularly for the next several decades, and a roughly thirty percent of their extant correspondence spanning more than fifty years of friendship can be found in Hugh Witemeyer’s Pound/Williams: The Selected Letters of Ezra Pound and Williams Carlos Williams, published by New Directions in 1996. The early years of their friendship are briefly summarized on pages 3-5 of that book. Emerging from Pound would be two thick edges connecting him as major influence upon both Louis Zukofsky and Basil Bunting. Pound and Zukofsky’s published correspondence makes for engrossing reading: Pound sought to cast Zukofsky as an admiring pupil and ersatz disciple/adopted son, with both men making early references to Zukofsky as “sonny” and Pound as “papa.” Zukofsky proved less tractable than Pound would have wished, however, and their relationship began to show serious signs of strain, especially following Zukofsky’s 1933 visit to Rapallo, which Pound and Williams had financed. Thinner lines might be drawn from Pound to Rakosi, who Pound published in 1928 in his magazine The Exile and in his Active Anthology, and to Oppen, who, thanks to Zukofsky’s mediation, published a volume of Pound’s critical prose, including How to Read, in 1932, was also included in Active Anthology, and for whose 1934 collection Discrete Series Pound wrote the preface. Fainter lines from Pound (indicating influence) might also be traced to both Reznikoff and Niedecker, both of whom admired and generally wrote in accordance with Pound’s imagist-era poetic prescriptions.

Williams was a far less domineering and dictatorial influence than Pound, though he served as an important American-based elder statesman and first-generation modernist figurehead for the group. Despite being Zukofsky’s elder by more than 20 years, Williams quickly came to respect Zukofsky as a superb editor and trust him as a valued poetic interlocutor, inviting him to edit the unpublished manuscript for what would become The Descent of Winter less than a month after their first meeting. In addition, Williams provided important linkages between Zukofsky and the peripheral “Objectivists” Robert McAlmon, Emanuel Carnevali, and Richard Johns. Williams also helped serve as a buffer and American counterweight to Pound, modeling a form of artistic independence from the often-aggressive Pound for the younger writers in the group. Williams also contributed to the development of the critical language Zukofsky used in presenting the group, suggesting for example in one of his earliest letters to the younger poet that Zukofsky’s poems had not “been objectivized in new or fresh observations.”23The Correspondence of William Carlos Williams and Louis Zukofsky, 11. Williams also influenced or at least agreed with others in the group in his repeated emphases on the importance of making “contact” with what he called the “primitive and actual America,” with “holding firm to the vernacular,” and insisting that they “make of [their] words a new form: to invent, that is, an object consonant with [their] day.”24The first two quotations come from an editorial “Comment” he published in the second issue of Contact in 1932 and the latter is taken from Williams description of objectivism in his 1951 Autobiography.

Perhaps even more importantly, Williams also used his own reputation and role as an occasional editorial advisor to provide Zukofsky and others in the group access to a succession of little magazines, like Johns’ Pagany and his own Contact, who sought the credibility that an association with Williams would provide their publications. He was similarly instrumental to the plans of both “Objectivist” book publishing endeavors, and his collaboration with Reznikoff, Zukofsky, and the Oppens in founding the Objectivist Press in September 1933 would necessitate the drawing of a thickly knotted bundle of connections between all of the principals. As detailed elsewhere on this site, the limited access to print enjoyed by Zukofsky and the other “Objectivists” from 1928 to 1935 would have been far more circumscribed were it not for their association with both Pound and Williams.

A network graph covering the five-year period from 1928 to 1933 would depict Bunting, Niedecker, and Rakosi as the most peripheral members of the group, in no small part because of their geographic distance. Apart from six months in New York City in late 1930-early 1931, Bunting spent these years in Europe, corresponding with just Pound, Zukofsky, and Williams from this group, though he did, thanks to facilitation from Zukofsky, develop an early admiration for Niedecker’s writing.25In 1928, Bunting was living in London and writing musical criticism for The Outlook. The newspaper folded that year and Bunting had rejoined Pound at Rapallo by March 1929, and apart from his wedding and six month interlude/honeymoon in New York City, spent most of his time there until departing in late 1933 for the Canary Islands, where he lived until the middle of 1936. Before meeting Reznikoff, Williams, and the Oppens on her first trip to New York City in late fall 1933, Niedecker had been living in rural Wisconsin and had corresponded only with Zukofsky. Rakosi was teaching high school English and enrolled in medical school in Texas during these years; the first of his fellow “Objectivists” he met personally was Zukofsky, and that didn’t happen until after his move to New York City in 1935, at which time much of the group’s energy had already dissipated.

The Shadow of Ezra Pound

What such a visualization would immediately make apparent is the way in which the main arteries of the Objectivist nexus traverse not just through Zukofsky and Williams, but also through Ezra Pound. The roots of the “Objectivist” nexus were nearly all entangled in some way with the sprawling, colonizing (though frequently generous) ambitions of the Rapallo-based poet. While less immediately apparent than Zukofsky or even Williams, Pound’s efforts as a behind the scenes orchestrator, advisor, and would-be impresario were crucially significant in both providing the impetus for Zukofsky’s efforts to assemble and perpetuate this group as well as providing the platform for the invention of a “movement” in the first place. It was Pound who served as a locus (through letters) of ideas, encouragement, and not-infrequent provocation for Zukofsky, Bunting, and Williams, the three members of the group with whom he carried on regular correspondence throughout the 1920s and 1930s.26Williams he knew from their days together at Penn, Bunting he had known for some time as a co-dweller at Rapallo, and Zukofsky had written him with admiration for both his prose statements and the poetic accomplishments of his early Cantos, the first sixteen of which had been published in Paris by Bill Bird’s Three Mountains Press in 1925. Pound also corresponded with George Oppen during these years, though their correspondence was mainly confined to Oppen’s role as a publisher of Pound’s writing.

Despite his centrality to the formation of the “Objectivist” nexus, I have chosen not to include Pound as a core “Objectivist” here, for two reasons. First, there is no shortage of published material examining Pound’s life and career, and second, apart from his consenting to have two of his poems of questionable merit included in Zukofsky’s An ‘Objectivists’ Anthology, Pound never gave any indication of voluntary affiliation with the label. Zukofsky had also wanted to include Pound in his issue of Poetry, ideally through the publication of a Canto, but Pound resisted Zukofsky’s several written entreaties. In the end, Zukofsky’s contributor notes indicate that he had planned to include a blank page in the issue as Pound’s contribution to the issue:

The editor also regrets the omission of a blank page representing Ezra Pound’s contribution to the issue—a page reserved for him as an indication of his belief that a country tolerating outrages like article 211 of the U. S. Penal Code, publishers’ “overhead,” and other impediments to literary life, “does not deserve to have any literature whatsoever.” Mr. Pound gave over to younger poets the space offered him.“27Poetry 37:5 (February 1931), 295.

This is not to say that Pound somehow held Zukofsky in low-esteem. His regard for Zukofsky and his fellow “Objectivist” (and former secretary) Basil Bunting was perhaps made most apparent when he dedicated his 1938 book Guide to Kulchur “To Louis Zukofsky and Basil Bunting strugglers in the desert.” Zukofsky in turn had already publicly declared his position viz a viz the elder poet, dedicating An “Objectivists” Anthology to Pound and referring to him there as “still for the poets of our time / the / most important.”28An “Objectivists” Anthology, 27. For his part, Bunting would offer his own moving assessment of Pound’s poetic accomplishment through his later short poem “On the Fly-Leaf of Pound’s Cantos,” which begins “There are the Alps. What is there to say about them? / They don’t make sense” before this concluding stanza: “There they are, you will have to go a long way round / if you want to avoid them. / It takes some getting used to. There are the Alps, / fools! Sit down and wait for them to crumble!”29The Poems of Basil Bunting, 117.

Pound’s writing on poetics were also important to the group, particularly the principles he had developed while promoting “Des Imagistes.” In a December 7, 1931 letter to Pound, Zukofsky confided that he viewed his then in-process long poem “A” as “following out of your don’ts almost to the letter,” referring to Pound’s well-known “A Few Don’ts by an Imagiste.”30Pound/Zukofsky, 110-111. Similarly, Charles Reznikoff recalled in a 1969 interview with L.S. Dembo:

When I was twenty-one [c. 1915], I was particularly impressed by the new kind of poetry being written by Ezra Pound, H. D., and others, with sources in French free verse. It seemed to me just right, not cut to patterns, however cleverly, nor poured into ready molds—that sounds like an echo of Pound—but words and phrases flowing as the thought; to be read just like common speech—that sounds like Whitman—but for stopping at the end of each line: and this like a rest in music or a turn in the dance.31Contemporary Literature, Spring 1969, 194.

When asked about his recollections of his conversations with Oppen and Zukofsky regarding ‘objectivist technique,’ Reznikoff told Dembo:

We picked the name “Objectivist” because we had all read Poetry of Chicago and we agreed completely with all that Pound was saying. We didn’t really discuss the term itself; it seemed all right—pregnant. It could have meant any number of things. But the mere fact that we didn’t discuss its meaning doesn’t deprive it of its validity. … I think we all agreed that the term “objectivism,” as we understood Pound’s use of it, corresponded to the way we felt poetry should be written. And that included Williams, too. What we were reacting from was Tennyson. We were anti-Tennysonian. His kind of poetry didn’t represent the world we knew-the streets of New York or of East Rutherford or Paterson. It might have represented the idyllic countryside where Tennyson lived, I don’t doubt, or the world in which Swinburne lived–that semi-classical world. We recognized its validity; I’m sure we all felt how good were things like “the hounds of spring are on winter’s traces” or the beginning of “The Lotos-Eaters.” Some of it was magnificent, but it wasn’t us.32Contemporary Literature, Spring 1969, 196-197.

In his interview with Dembo published in the same issue of Contemporary Literature, Rakosi prefaced his pointed criticism of Pound’s personal grandiosity and the epic tone adopted in the Cantos by stating that “I had better admit that I believe that Pound’s critical writing—particularly the famous “Don’ts” essay—is an absolute foundation stone of contemporary American writing.”33”Carl Rakosi,” 180. In an unpublished note titled “The Objectivist Connection,” Rakosi had written “I had heeded Pound’s advice on writing. I had immediately recognized it as right and helpful and had incorporated it as my own working principle” (UCSD Special Collections, MSS 0355, Box 4, Folder 15). In an unpublished draft of his own autobiography as a writer, Rakosi wrote

You might say that Pound’s axioms on writing re-educated me and whatever I wrote after that, followed those axioms. They made such basic sense that they became my second nature. To all intents and purposes they were my principles and it became unthinkable for me to treat subject matter evasively or to use any word that did not (to use Pound’s expression) “contribute to its presentation.” Never, in other words, to be prolix or flaccid or unnecessarily abstract.”34UCSD Special Collections, MSS 0355, Box 4, Folder 4.

Similarly, Pound and Williams were the first two authors the Oppens chose to publish under the To, Publishers imprint; Mary Oppen would tell Serge Fauchereau in a 1976 interview that “We understood the importance of Pound, and to us he was a tremendous figure.”35Speaking with George Oppen, 132.

As important as Pound was as a poetic predecessor and influence on the “Objectivists,” he also played a much more direct role in the group’s formation as a publisher, facilitator, and erstwhile impresario. His short-lived magazine The Exile (four issues appeared in 1927 and 1928) might even be considered something of a proto-“Objectivist” publication,36Tom Sharp has argued that the magazine was the group’s “first public meeting place” and that by “express[ing] many of the principles, especially about the importance of group activity, that Pound continued to impress upon them” it placed the “Objectivists” firmly within that “tradition in poetry for which Pound was the principal spokesman” (http://sharpgiving.com/Objectivists/sections/01.history.html). as it featured work by Zukofsky, Williams, Rakosi, McAlmon, and Howard Weeks, each of whom would later be featured in Zukofsky’s “Objectivist” issue of Poetry.37Zukofsky’s first major publication, “Poem Beginning ‘The'” appeared in The Exile 3, and the fourth and final issue of The Exile included another dozen or so pages from Zukofsky. Williams’ “The Descent of Winter,” which Zukofsky had been instrumental in editing, was published in The Exile 4. Williams wrote to Pound on May 17, 1928: “Your spy Zukofsky has been going over my secret notes for you. At first I resented his wanting to penetrate- now listen! – but finally I sez to him, All right, go ahead. So he took my pile of stuff into the city and he works at it with remarkably clean and steady fingers (to your long distance credit be it said) and he ups and choses a batch of writin that yous is erbout ter git perty damn quick if it hits a quick ship – when it gets ready – which it aren’t quite yit. What I have to send you will be in the form of a journal, each bit as perfect in itself as may be. I am however leaving everything just as selected by Zukofsky. It may be later that I shall use the stuff differently.” (Pound/Williams, 82) Zukofsky and Williams had first met in April of that year, which means that Williams had known Zukofsky for less than 2 months at the time that he sent Pound this remarkable indication his editorial trust. Pound published four poems by Rakosi in The Exile 2 and his poem “Extracts from A Private Life” in The Exile 4. McAlmon’s short story “Truer than Most Accounts” appeared in The Exile 2 and an essay of his on Gertrude Stein was included in The Exile 4. Weeks’ poem “Stunt Piece” was published in The Exile 3 and was the only place his work had appeared before Zukofsky included him in his “Objectivist” issue of Poetry.

In addition to The Exile, Pound also included a number of “Objectivist” writers in two anthologies he edited in the early 1930s, featuring Williams, Zukofsky, Bunting, McAlmon, Eliot, Weeks, Tyler, and Carnevali in his 1932 Profile anthology and including work by Williams, Bunting, Zukofsky, Oppen, and Eliot in his 1933 Active Anthology. Pound also published a brief note in the “Books on Review” section of the February 21, 1933 issue of Contempo praising An “Objectivists” Anthology as “the first serious attempt since my first Imagiste collection to clean up the mess of contemporary poetry by means of an anthology, and ought to establish just as definite a date.”38Contempo, III: 6 (February 21, 1933), 7.

Not only did Pound publish a number of these writers before and after they became associated with the label “Objectivist,” he was also instrumental in recommending that Zukofsky (and other of his disciples) join with other writers to publish and promote significant literature in the United States. In fact, Pound had first begun urging Zukofsky to “form a group” to continue the momentum and impulse of his magazine The Exile in his second ever letter to Zukofsky, sent in February 1928, writing: “Also any of your contemporaries with whom you care to associate. Somebody OUGHT to form a group in the U.S. to make use of the damn thing now that I have got in motion. Failing development of some such cluster I shall stop with No. 6 [of The Exile].”39Pound/Zukofsky, 6.

In his very next letter to Zukofsky, Pound attempted to catalyze the formation of such a cluster by forwarding his old friend William Carlos Williams’ address to Zukofsky and suggesting that he introduce himself. Zukofsky did so almost immediately; the two writers first met in a NY restaurant April 1, 1928, where Zukofsky asked Williams to read his work, and volunteered his own services as an editor of Williams’ unpublished manuscripts. Both liked each other immediately and each quickly sent back to Pound separate reports on their budding friendship. Their growing bond would serve as the basis for what became the “Objectivist” cluster.

In August 1928, after receiving reports that Zukofsky and Williams had hit it off, Pound wrote Zukofsky another lengthy letter, urging him to

make an effort toward restarting some sort of life in N.Y.; sfar as I know there has been none in this sense since old Stieglitz organized (mainly foreign group) to start art. … I suggest you form some sort of gang to INSIST on interesting stuff (books) (1.) being pubd. promptly, and distributed properly. 2. simultaneous attacks in as many papers as poss. on abuses definitely damaging la vie intellectuelle. … there are now several enlightened members of yr. body impolitic [meaning the United States] that might learn the val. of group action.40Pound/Zukofsky, 11.

Acting on Pound’s suggestions, Zukofsky contacted several more of the writers Pound had recommended to him, including Joseph [Joe] Vogel, an aspiring young writer and recent graduate from Hamilton College where, like Pound, he had studied Romance languages. Vogel responded to Zukofsky’s overtures by writing directly to Pound, and Pound sent Vogel his beliefs regarding “the science of GROUPS” in a November 21, 1928 letter, instructing him to share its contents with Zukofsky. His advice included the following recommendations:

[A]t the start you must find the 10% of matters that you agree on and the 10% plus value in each other’s work. [Second, he was not to expect a group to remain constant:] Take our groups in London. The group of 1909 had disappeared without the world being much the wiser. Perhaps a first group can only prepare the way for a group that will break through. The one or two determined characters will pass through 1st to 2nd or third groups. [Thirdly, there was] No use starting to crit. each other at start. Anyhow it requires more crit. faculty to discover the hidden 10% positive, than to fuss about 90% obvious imperfection. You talk about style, and mistrusting lit. socs. etc. Nacherly. Mistrust people who fuss about paint and finish before they consider girders and structure.” Fourth, “You ’all’ presumably want some sort of intelligent life not dependent on cash, and salesmanship. . . . Point of group is precisely to have somewhere to go when you don’t want to be bothered about salesmanship. (Paradox?? No.) … When you get five men who trust each other you are a long way to a start. If your stuff won’t hold the interest of the four or of someone in the four, it may not be ready to print.41The Selected Letters of Ezra Pound, 219-221. Here Vogel is named “James” instead of “Joseph”.

Vogel replied with some hesitation, prompting an exasperated outburst from Pound: “Dear Vogel: Yr. painfully evangelical epistle recd. if you are looking for people who agree with you!!!! How the hell many points of agreement do you suppose there were between Joyce, W. Lewis, Eliot and yrs. truly in 1917; or between Gaudier and Lewis in 1913; or between me and Yeats, etc.?,” and telling Vogel that if respected decent writing, writing which expressed a man’s ideas, he ought to exchange his with others who have “ideas of any kind (not borrowed clichés) that irritate you enough to make you think or take out your own ideas and look at ’em.”42The Selected Letters of Ezra Pound, 222. More on Vogel/Pound correspondence in Paideuma 27:2-3 [Fall/Winter 1998], 197-225.

Not only did Pound introduce Zukofsky to both Williams and Vogel (who would not be associated with the “Objectivists”), he also connected Zukofsky to several other of his acquaintances who would become members of the “Objectivist” group, including Charles Henri Ford, the young editor of Blues; Basil Bunting, whom William Butler Yeats famously described as “one of Ezra’s more savage disciples”;43The Letters of W.B. Yeats, 759. Ed. Allan Wade (MacMillan, New York, 1954) Samuel Putnam, a Paris-based poet and translator who would later publish Zukofsky and other “Objectivists” in his magazine The New Review; and Howard Weeks and Carl Rakosi, both of whom he had published in The Exile.44Pound first mentions Rakosi in a letter to Zukofsky filled with advice about assembling his guest edited issue of Poetry dated 25 October 1930, indicating that he “may be dead, I wish I cd. trace him” and passing along his last known address in Kenosha, Wisconsin (Pound/Zukofsky, 51). Pound was also indirectly responsible for Zukofsky’s meeting the Oppens, since the Oppen-Zukofsky friendship began with George Oppen’s chance discovery of the third issue of The Exile (which featured Zukofsky’s “Poem Beginning ‘The'”) while browsing the poetry section at the Gotham Book Mart shortly after his and Mary’s arrival in New York City in the late 1920s.45Mary Wright, the wife of designer Russel Wright, introduced the Oppens to Louis Zukofsky at a party sometime in 1928. See Mary Oppen’s account of their meeting in Meaning a Life, 84-85.

Zukofsky also attempted to make recommendations of his friends and acquaintances in the “Objectivist” circle to Pound, though Pound generally preferred giving advice and making discoveries than receiving either. For example, Zukofsky sent Pound work by Oppen, Rakosi, Reznikoff, and Rexroth when Pound was assembling his Active Anthology in 1933, but of Zukofsky’s submissions Pound only included work by Rakosi (whom he had previously published in The Exile) and Oppen (who had published Pound) in the final selection. While Pound never became enthusiastic about the work of any of Zukofsky’s acquaintances, Zukofsky ‘discovered’ and introduced him to Reznikoff, Oppen, Niedecker, Rexroth, and Henry Zolinsky, among others.46Pound and Zukofsky’s surviving letters from 1930 make several references to Reznikoff and Zukofsky’s “sincerity and objectification” essay on Reznikoff’s work. While Pound expressed vague praise for Reznikoff’s work, he would reject it for inclusion in his Active Anthology. Zukofsky made reference to his having sent Pound several unpublished Oppen poems in a letter dated June 18, 1930. This manuscript was recently been found in the Pound papers held at Yale by the scholar David Hobbs and published by New Directions as 21 Poems. See pp. 26-44 of Pound/Zukofsky for the letters Pound and Zukofsky exchanged during the period in question. Niedecker is first mentioned in the Pound/Zukofsky correspondence in February 1935, when Zukofsky writes “Glad you agreed with me as to the value of Lorine Niedecker’s work and are printing it in Westminster,” a reference to the Spring-Summer 1935 issue of Bozart-Westminster, which Pound edited with John Drummond and T.C. Wilson and included several poems and a dramatic scenario by Niedecker (Pound/Zukofsky, 161). This was a particularly strained time in the Pound/Zukofsky relationship, largely exacerbated by political differences over fascism and economic theory, and in his especially nasty response, Pound dismissed Niedecker’s work and insulted Zukofsky’s critical acumen.

Ultimately, the effect of Zukofsky’s relationship with Pound on the “Objectivists” was decidedly mixed. Pound initiated a number of important relationships for Zukofsky, using his prestige and relationship with prominent editors to help him gain access to prominent publications, including Poetry, Hound & Horn, and The New Review, but Pound’s difficulty and volatility meant that when things turned sour between Pound and these publications, Zukofsky was also impacted negatively by implication. While some contemporary attacks on Zukofsky may have been the result of personal jealousy or genuine aesthetic disagreement, a greater number of them appear to center on his relationship to Pound, who was suspect both for his bullying bravado and increasingly erratic political and economic views. Joseph Vogel, the writer that Pound had encouraged to form a group with Zukofsky in 1928, publicly denounced Pound in October 1929 in New Masses as “the dean of corpses that promenade in graveyards” and suggested that Pound had “tried to organize a group of writers in this country, but the only success—or harm—he achieved was the taking of a smaller Pound under his wings, namely Louis Zukofsky.”47”Literary Graveyards,” 30. The editors of The Hound & Horn had similar views, with Yvor Winters writing to Lincoln Kirstein in 1932 that “[o]ur own generation, and the kids who are coming up, seem to be divided more or less clearly between those whose intellectual background is incomprehensible to the older men and who therefore remain largely meaningless to them, and those who imitate them feebly and flatter them in numerous ways (Zukofsky is the most shameless toady extant) and who are therefore praised by them.”48The Selected Letters of Yvor Winters, 195. Zukofsky’s relationship with Pound would even make him suspect to others of the “Objectivists,” particularly those who, like Vogel, became most active in Communist Party politics. In his review of Charles Reznikoff’s In Memoriam: 1933, published in New Masses in March 1935, Norman Macleod deplored the fact that “a man of Reznikoff’s caliber should be forced to descend to publication by the Objectivist Press, an outfit controlled so far as I can learn by that consummate ass and adulator of Herr Ezra Pound (Heil Hitler and may all his descendants descend), Louis Zukofsky.”49”Pain Without Finish,” 23-24. Zukofsky bore most of these attacks in silence, preferring to let his work stand for itself, but his reputation was certainly damaged by his closeness to Pound, and their perceived closeness does appear to have impaired the ability of many of Zukofsky’s contemporaries to assess his accomplishments dispassionately.50Williams and Zukofsky both contributed to Charles Norman’s 1948 pamphlet The Case of Ezra Pound, giving their views of their old friend as he was preparing to stand trial for treason. Zukofsky wrote: “I should prefer to say nothing now. But a preference for silence might be misinterpreted by even the closest friends. When he was here in 1939, I told him that I did not doubt his integrity had decided his political action, but I pointed to his head, indicating something had gone wrong. … He approached literature and music at that depth. His profound and intimate knowledge and practice of these things still leave that part of his mind entire. … He may be condemned or forgiven. Biographers of the future may find his character as charming a subject as that of Aaron Burr. It will matter very little against his finest work overshadowed in his lifetime by the hell of Belsen which he overlooked” (55-57).

Other “Objectivists”

In addition to Pound and the seven writers already described as core “Objectivists,” Zukofsky’s two “Objectivist” publications included more than twenty other writers, each of whom should also be considered part of what Rachel Blau DuPlessis and Peter Quartermain have termed the “Objectivist nexus.”51In their edited collection The Objectivist Nexus: Essays in Cultural Poetics, published in 1999 by the University of Alabama Press. Of these, Robert McAlmon and Kenneth Rexroth perhaps deserve special note, as they were the only other authors to appear in both foundational “Objectivist” publications, and each participated in abortive publication schemes involving other members of this group during the 1920s and 1930s. Recalling the network graph visualization imagined earlier ,I have chosen not to include them among the core largely because both writers remained on the fringes of the group. While Niedecker and Rakosi were similarly peripheral in the 1930s, their subsequent careers, particularly their activity in the 1960s, showed that they (and other members of the core group) thought of themselves as members of a network in ways that McAlmon and Rexroth did not. Neither McAlmon nor Rexroth ever developed deep connections with any but one other member of the group (Williams in McAlmon’s case and Zukofsky in Rexroth’s).

Writers Published in the “OBJECTIVISTS” 1931 issue of Poetry

As a group, the “Objectivists” were invented and publicly presented through the publication of the “OBJECTIVISTS” 1931 issue of Poetry magazine, a special “number” which the magazine’s regular editor, Harriet Monroe, had entirely given over to Louis Zukofsky at the urging of Ezra Pound.52More detail about the editing of this issue of Poetry magazine can be found elsewhere on this site. With space given to him, Zukofsky set out an “Objectivist” program, advanced the critical principles of “sincerity” and “objectification” in a critical essay on the poetry of Charles Reznikoff, provided his own translation of a brief essay by his friend René Taupin on the poetry of André Salmon, and presented poetry and prose from more than twenty contributors. Biographical sketches for each of these original “Objectivists” are given below, in order of their appearance in the February 1931 issue of Poetry.

Carl Rakosi, Four Poems

Core “Objectivist.”

Louis Zukofsky, Seventh movement of “A”

Inventor of the term “Objectivist” and chief instigator of the group.

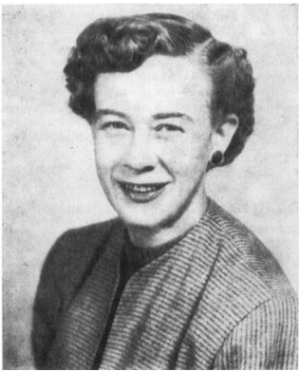

Howard and Virginia Weeks passport photo, 1922

Howard Weeks, “What Furred Creature“

Howard Percy Weeks was born on December 13, 1899 in Rochester, New York to Percy Benson Weeks, a varnish salesman, and F. Estelle “Stella” Bush. Weeks enrolled at the University of Michigan in 1918 and published his own writing regularly in The Michigan Chimes, a student magazine for which he served as humor writer. Weeks graduated in 1921 with a bachelor’s degree from the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts and married Virginia Morrison, the daughter of William Morrison and Ella Peppers, in Detroit on September 26, 1922.

The couple applied for a passport that same year to take a three-month honeymoon in Europe, stating their intention to depart from Montreal in late September and travel to England, France, Switzerland, Germany, and Italy. Like his older brother Albert, Weeks worked as a journalist. I’ve been unable to uncover much more about his life and career apart from the fact that he died of a streptococcus infection after an extended illness on June 10, 1928, nearly three years before the publication of the “Objectivists” issue of Poetry.53His obituary appeared in the Michigan Free Press.

As a poet, Weeks had been “discovered” by Ezra Pound, who published his poem “Stunt Piece” in the third issue of The Exile, and thought enough of it to include it in his Profile anthology in 1932, writing: “By 1928 Mr Weeks found material for satire in Mr. Eliot’s imitators and detached the externals.”54Profile, 111. In his essay on Small Magazines published in the November 1930 issue of The English Journal, Pound wrote: “I printed very little of Weeks because he seemed to me a man of great promise; one felt that his work was bound to be ever so much better in the course of the next few months. The few months were denied him.”55See: http://library.brown.edu/cds/mjp/pdf/smallmagazines.pdf#page=13 Zukofsky wrote to Pound on November 6, 1930 with detailed responses to some of Pound’s inquiries about his editing of what would become the “OBJECTIVISTS” 1931 issue of Poetry. Near the end of that letter he asked Pound: “Never saw too much in Weeks either, but very little outside of Xile was printed—Have you any?”56Pound/Zukofsky, 68. Pound presumably sent Zukofsky some of Weeks’ work, including “Furred Creature,” which Zukofsky included in Poetry. There is no evidence that Pound, Zukofsky, or anyone else in the “Objectivist” circle ever met Weeks in person, and only Pound appears to have corresponded with him before his death in 1928.

Robert McAlmon, “Fortuno Carraccioli“

Robert Menzies McAlmon was born in Clifton, Kansas on March 9, 1895, the youngest of ten children in a family headed by his father, John Alexander McAlmon, an Irish-born Princeton graduate and Presbyterian minister. McAlmon spent much of his childhood in Minnesota and Madison, South Dakota, and described much of his upbringing, including his close friendship with Gore Vidal’s father Eugene, in his fictionalized 1924 memoir Village: As It Happened Through a Fifteen Year Period. At sixteen he left school to pursue a career as a journalist, working briefly as the editor of a small city paper before being dismissed when the owner discovered he had lied about his age. McAlmon then worked in advertising for the National Advertising Agency and briefly attended college before joining the Army Air Corps near the end of World War I. Following the war’s end, McAlmon enrolled at the University of Southern California and worked as a feature editor for the Rockwell Field Weekly Flight, an aviation newspaper published out of San Diego, but eventually left California and moved to New York City.

In 1920, shortly after arriving in New York City, McAlmon met William Carlos Williams at a party hosted by the avant-garde poet Lola Ridge. McAlmon and Williams quickly struck up a friendship and soon after became joint publishers of Contact, a cheaply-produced little magazine. Together, they published four issues of Contact between December 1920 and the summer of 1921.57Williams published a fifth and final issue of Contact with Monroe Wheeler in June 1923, and revived the title of the magazine for a second run in 1932. In February 1921, McAlmon entered into marriage of convenience with Bryher (Annie Winifred Glover), H.D.’s lover and the daughter of Sir John Ellerman, one of the wealthiest men in Britain. Following their marriage, McAlmon and Bryher moved to London (which McAlmon hated) and then to Paris, where McAlmon used his father-in-law’s wealth to found the Contact Publishing Company and publish important modernist writing under the Contact Editions imprint, including books by his wife Bryher (Annie Ellerman), Gertrude Stein, Ernest Hemingway, Williams and himself.58For a good description of Bryher/Ellerman’s and McAlmon’s relationship, see Shari Benstock’s Women of the Left Bank: Paris 1900-1940, especially pp. 357-362.

McAlmon’s first book, a collection of poems entitled Explorations, was published in 1921 by Harriet Shaw Weaver’s The Egoist Press. McAlmon followed Explorations with several more books published by his own Contact Publishing Company throughout the 1920s. These included the short story collections A Hasty Bunch (1922) and A Companion Volume (1923); two loosely-autobiographical, largely plotless prose works: Post-Adolescence (1923) and Village (1924); Distinguished Air: Grim Fairy Tales (1925), a collection of stories dealing with the 1920s gay subculture in Berlin; and the poetry collections The Portrait of a Generation (1926) and North America, Continent of Conjecture (1929).

McAlmon and Bryher divorced in 1927 and Contact Editions ceased publishing new work in 1929. McAlmon shuttled between Europe and the United States for much of the 1930s, including a longish stint spent in Albuquerque, New Mexico. He published three books in the decade, including the story collection The Indefinite Huntress and Other Stories (1932) with the Black Sun Press in Paris, the poetry collection Not Alone Lost (1937) with James Laughlin’s New Directions Press and Being Geniuses Together (1938), his memoir of the years he spent in Paris among artists and expatriates, published in London by Secker and Warburg. McAlmon was living in France when the Germans occupied Paris, but managed to depart Nazi-occupied France (via Portugal) for the United States in 1940. Following his return to the United States, McAlmon worked for several years for his family’s medical supply company and moved around the southwestern United States, battling alcoholism. He died in Palm Springs, California on February 2, 1956, leaving behind a handful of unpublished manuscripts.

Following his death, the University of Nebraska English professor Robert Knoll authored a brief study of McAlmon’s life and work, Robert McAlmon: Expatriate Publisher and Writer (1959), which included a forward by William Carlos Williams, and shortly thereafter edited McAlmon and the Lost Generation: A Self Portrait (1962), which was largely comprised of McAlmon’s autobiographical writing. In 1963, more sexually explicit versions of some of the stories included in Distinguished Air were published by Belmont Books in New York under the title There Was a Rustle of Black Silk Stockings, and in 1968, Kay Boyle revived and revised McAlmon’s Being Geniuses Together, interspersing her own reminiscences as interchapters between lightly edited versions of McAlmon’s original work. This new edition of Being Geniuses Together was published to some acclaim by Doubleday.

In 1975, Sanford Smoller published a biography of McAlmon, entitled Adrift Among Geniuses, with Pennsylvania State University Press, and in 2007, the University of Illinois Press published The Nightghouls of Paris, a previously unpublished work of thinly veiled autobiographical fiction which Smoller had edited from a surviving manuscript. Many of McAlmon’s papers are now held by Yale University’s Beinecke Library.

Joyce Hopkins, “University: Old-Time“

“Joyce Hopkins,” was a fictional pseudonym invented by Zukofsky, probably intended as a literary in-joke combining the names of James Joyce and Gerard Manley Hopkins. Zukofsky fashioned the one-line poem “University: Old-Time” from a line in a letter describing the efforts of his friend Irving Kaplan’s wife Dorothy to help elderly citizens in Napa, California apply for state pensions.59Zukofsky offers a gloss on the poem in a December 14, 1931 letter to Ezra Pound: “Jerce ‘opkins, again? That’s funny!! Napa—a kind of weed growing in Napa, Calif. I don’t know why Persephone’s husband, romanized, shdn’t be on the west coast now. I don’t know that Napa has a university, but it might as well have. The literal meaning of this famous epigram was the bare statement in a letter of Roger Kaigh [a pseudonym for Kaplan] to Mr. L.Z—D. (Dorothy his spouse, who was dispensing pensions to old folk) is in Napa trailing the sterilized. I added the title & lower-cased napa—which word you can find in Webster’s international. I looked it up after I myself <had> begun to doubt the meaning of the poem. The allegorical meaning is that L.Z. in Wisconsin was Pluto in hell following a lot of emasculated peripatetics (tho’ it is even doubtful these walked or were ever unemasculated). The anagogical meaning is that even evil (Dis) implies redemption” (Pound/Zukofsky, 120-121). Kaplan is probably the same person referred to in several of Zukofsky’s letters at Roger Kaigh and at several points in early movements of “A” as Kay.

Irving Kaplan was born in Dziatlava, Poland on September 23, 1900, and emigrated to New York City with his parents while a young child. He became a U.S. citizen when his father Morris Kaplan was naturalized in 1910 or 1911, and attended public schools in New York City before enrolling at the City College of New York for a year. After a year at City College, Kaplan transferred to Columbia University, where he earned his bachelor’s degree in 1923 and befriended Zukofsky, Whittaker Chambers, Meyer Schapiro, and other classmates. Kaplan did some graduate work at Columbia and attended Fordham Law School in 1928 and 1929, but left without completing a law degree.

On September 6, 1928, Kaplan married Dorothy Herbst in Manhattan, and the couple lived at 221 Linden Boulevard, near Prospect Park in the Flatbush neighborhood of Brooklyn, where Kaplan worked as an accountant. In the fall of 1929 the Kaplans moved to Berkeley, California, where Dorothy enrolled in graduate school at the University of California and Irving worked as an economist for the Pacific Gas and Electric Company. Zukofsky visited the Kaplans in Berkeley during the summer of 1930, and wrote large portions of the sixth and seventh movements of “A” from the attic of their home at 1110 Miller Avenue before taking up his teaching position that Fall at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

In the spring of 1932, Zukofsky and Jerry Reisman traveled to Berkeley to visit the Kaplans again, and Reisman remembered Kaplan as a frequent visitor to Zukofsky’s apartment in New York City in the early-mid 1930s.60For more on Roger Kaigh/Irving Kaplan, see Andrew Crozier’s “Paper Bunting” in Sagetrieb 14:3 (Winter 1995), 45-75. The Kaplans left California in July 1935 for Washington D.C., where Irving worked as a statistician and administrator for a number of federal government agencies, including the Works Progress Administration, the Federal Works Administration and the Office of Production Management (also known as the War Production Board). From late 1935 until the summer of 1938, he worked in Philadelphia under the direction of Harold Weintraub as the Associate Director of the National Research Project on Reemployment Opportunities and Recent Changes in Industrial Techniques of the Works Progress Administration. In 1937, as Whittaker Chambers began to plan his defection from the Soviet underground, Kaplan helped his old college friend and fellow Communist find a job with the WPA.61Chambers testified before HUAC in 1948 that while beginning to look for government work, he had been referred to Kaplan, his old college friend, and spent an evening with him in Philadelphia, and that within a matter of days Kaplan had arranged a position for Chambers with the federal government. Chambers began work as a “Report Editor” on the National Research Project in October 1937 and was furloughed in February 1938, following which time he found literary translation work through his old college friend Meyer Schapiro.

In 1938, Kaplan left the WPA and returned to Washington D.C. to take a job in the Justice Department working for the Assistant Attorney General Thurman Arnold in connection with the Temporary National Economic Committee. In February 1940, Kaplan took a position as an economist with the Federal Works Administration, and remained there until 1942, when he transferred to the Office of Production Management.62The 1940 census lists the Kaplans as living at 5315 Edmunds Place in Washington, D.C. and records Kaplan as making $5400 a year as an economist for the Federal Works Administration. From July through December 1945, Kaplan worked for the finance department of the United States military government in Germany, serving in an important capacity as the economic advisor on liberated areas. From 1948 to 1952 Kaplan again worked under David Weintraub, spending these years as an economic officer for the United Nations.

Kaplan’s employment at the United Nations ended precipitously in 1952, however, when he has summoned to testify before HUAC after being the subject of accusations of subversive Communist activity levelled against him by Elizabeth Bentley and Whittaker Chambers.63Bentley accused him of being a member of the Silvermaster spy group and paying dues to the Perlo group. More context for Bentley’s accusations can be found in “The Shameful Years,” a HUAC report issued in December 1951. Kaplan’s testimony before HUAC in 1952 can be read here. Following his appearance before HUAC, which concluded with Congressman Donald Jackson stating that he was “personally convinced that [Kaplan] was a Communist and that he undoubtedly is a Communist today,” Kaplan was fired from his position at the United Nations and screened out of government employment.

Kaplan appears to have remained concerned with the United States’ relationship with the U.S.S.R. and other Communist states throughout the intervening decade, however, writing a letter to President Johnson objecting to U.S. military involvement in Vietnam in May 1964 and forwarding it to Senator Wayne Morse, praising Morse for his “valiant work on the issue involved … pressing our Government toward a policy of peace and reason.”64This letter was one of several letters opposed to U.S. involvement in South Vietnam which Morse submitted to the Congressional Record in 1964 and can be read in full at https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1964-pt9/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1964-pt9-10.pdf#page=40. About Kaplan’s later years I have been able to discover little, other than that the Social Security records list him as having died on July 17, 1988, aged 87.

Charles Reznikoff, “A Group of Verse“

Core “Objectivist.”

Norman Macleod, “Song for the Turquoise People“

Norman Wicklund Macleod was born in Salem, Oregon in 1906. While an undergraduate at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque in the late 1920s, Macleod founded a series of increasingly ambitious little magazines, including Jackass (1928), Palo Verde (1928-1929), The Morada (1929-1930), and Front (1930-1931), the latter two of which displayed Macleod’s growing interest in international literature and radical left-wing politics, and which published featured work by Pound, Zukofsky, and several other “Objectivists.”

Front ceased publication after its fourth issue, when Macleod moved to Los Angeles to attend graduate school the University of Southern California from 1931-1932. Before finishing his degree, Macleod moved to New York City, where he worked as a reader and circulation assistant for the publisher Harper & Brothers from 1932-1934. During his time in New York, Macleod befriended Zukofsky and Williams and even received Williams’ approval to take over editing the second run of Contact following Williams’ resignation in 1933, but the magazine folded before publishing any further issues.65See The Correspondence of WIlliams Carlos Williams and Louis Zukofsky, 146.

Macleod and Williams remained friends for several years, with Williams including a “Poem for Norman Macleod” in his 1935 collection An Early Martyr and Other Poems.66The Collected Poems of William Carlos Williams, Vol. 1, 401. In 1934, Macleod briefly left New York to attend the University of Oklahoma, but was back in New York City by 1935, when he married Vivienne Koch, a literary scholar who published an early critical study of Williams Carlos Williams’ poetry. With Koch’s encouragement, Macleod made a final attempt at graduate school, this time earning a master’s degree in English from Teachers College, Columbia University in 1936.

In 1939, Macleod helped William Kolodney found the Poetry Center at the 92nd Street Young Men’s Hebrew Association (now called the Unterberg Poetry Center at the 92nd Street Y), where he worked until 1942. In March of that year, Macleod appeared with Zukofsky and two other poets on a panel about democracy and the poet’s responsibility during wartime at the Poetry Center,67According to Barry Ahearn, Macleod and Zukofsky were joined by Robert Goffin and Sheamus O’Sheal in addressing the questions “What has American poetry contributed to the democratic tradition? What is the American poet’s responsibility in the present war?” (The Correspondence of William Carlos Williams and Louis Zukofsky, 300-301). and later that year Macleod left the Poetry Center to take a teaching job at the University of Maryland (where he edited the Maryland Quarterly from 1942-1944). In 1944, Macleod returned to New York, taking a teaching position at Briarcliff College (where he edited the Briarcliff Quarterly from 1944-1947). In October 1946, Macleod published a special William Carlos Williams issue of Briarcliff Quarterly and included Williams’s “Choral: The Pink Church,” a poem which had been set to music by Celia Zukofsky.

In 1946, Macleod and Koch divorced, and shortly thereafter Macleod left New York City again, embarking on a varied and peripatetic teaching career, holding positions over the next two decades at Lehigh University, Savannah State College (now Savannah State University), San Francisco State College (now San Francisco State University), and the University of Baghdad. Macleod accepted a position at Pembroke State University (now the University of North Carolina at Pembroke) in 1967, founded Pembroke magazine in 1969, and later directed the university’s Creative Writing program. In 1973, he received the Horace Gregory Award (a national award created in 1969 to honor emeritus faculty members for their social contributions to arts, letters and research) for his work as a poet, an editor, and a teacher, and he retired from both teaching and editing Pembroke in 1979, six years before his death in Greenville, North Carolina on June 5, 1985.

Macleod published several collections of poetry, including Horizons of Death (1934), Thanksgiving Before November (1936), We Thank You All the Time (1941), A Man in Midpassage (1947), Pure as Nowhere (1962), Selected Poems (1975), and The Distance: New and Selected Poems, 1928–1977 (1977). Macleod’s published prose works include two novels: You Get What You Ask For (1939) and The Bitter Roots (1941), and the autobiography I Never Lost Anything in Istanbul (1978). Macleod’s papers are now held by Yale University, the University of Delaware, and the University of New Mexico.68Yale has letters from Williams and Zukofsky, plus letters from Marty Rosenblum and Tom Sharp.

Kenneth Rexroth, “Last Page of a Manuscript“

Kenneth Charles Marion Rexroth was born in South Bend, Indiana on December 22, 1905, and recounted many of his early life experiences in his raucous 1966 memoir An Autobiographical Novel. Rexroth published his first poems in Charles Henri Ford’s little magazine Blues, where he appeared alongside Pound, Williams, and Zukofsky, as well as fellow “Objectivists” Carl Rakosi, Norman Macleod, Harry Roskolenko, and Richard Johns. His first wife Andrée Dutcher, a talented artist, even designed the cover of Blues 7.