In addition to the cluster of friendships among the various “Objectivist” writers initiated in the mid- to late-1920s and cemented by regular correspondence, the core “Objectivists” were also connected by their longstanding mutual interest in one another’s poetry. Through a series of little magazines, cooperative book publishing ventures, and other schemes, these writers spent considerable time and effort reading, publishing, and reviewing one another’s work, with several members of the group sending each other their new publications for the rest of their lives, in some cases more than fifty years after their initial association.

While the first explicitly “Objectivist” poems as such appeared in the February 1931 issue of Poetry, most of the poets included in that group had already been publishing their writing for some time, usually in some of the era’s many little magazines. In fact, William Carlos Williams, the oldest member of the group by more than a decade, published his first collection, Poems, in 1909, just a year after George Oppen, the youngest core “Objectivist,” was born. Apart from Williams, who published poetry and prose more or less continuously from 1909 until his death in 1963, the remainder of the “Objectivists” had two distinct periods of intense publication activity (from 1928-1935, and from 1959-1978) interrupted by almost 25 years during which some members of the group wrote almost nothing and those who continued writing found it very difficult to have their work published.

While each of the authors featured on this site enjoyed their own rich individual publication history, explored in greater depth on separate pages for each individual writer, this page will detail several of the collaborative publication efforts that various of these “Objectivist” writers participated in during their first period of activity (1928-1935), with a special emphasis placed on the several little magazines, anthologies and publishing cooperatives the “Objectivists” appeared in, edited, published, and financed.

“Objectivist” Publications

The “OBJECTIVISTS” 1931 issue of Poetry magazine

The seeds of what would be published in February 1931 as the “OBJECTIVISTS” 1931 issue of Poetry magazine had their roots in Louis Zukofsky and Ezra Pound’s correspondence, which began in the summer of 1927 when Zukofsky sent Pound his “Poem Beginning ‘The'” for consideration in Pound’s newly established magazine The Exile. Pound’s favorable response to Zukofsky’s poem and, later to his critical writing (it helped that one of Zukofsky’s essays was an appreciative and perceptive review of Pound’s Cantos), initiated a lively correspondence which intensified and broadened over the next several years as Zukofsky formed his own developing relationships with others in Pound’s circle of American contacts. In December 1929, Zukofsky sent Pound an article he had written on the poetry of Charles Reznikoff (which would later become the “Sincerity and Objectification” essay included in the “Objectivists” issue of Poetry), few months later, Pound began mentioning Zukofsky’s promise as a critic to Harriet Monroe of Poetry, telling her in March 1930: “I think you miss things. Criterion and H[ound] & Horn both taking on Zukofsky. If you can’t liven up the verse; you cd. at least develop the critical section.”1University of Chicago Special Collections. On September 26, 1930, Pound told Zukofsky he informed Zukofsky that he had recently gotten around to reading two of Zukofsky’s prose essays, including his piece on Reznikoff and told him “I don’t think either essay any use for Yourup = I think they both (after emendation) ought to appear in Poetry. & will write same to Harriet … today or tomorrow = and if you like will edit the mss when I get back to Rapallo.”2Pound/Zukofsky, 43-44. True to his word, he dashed off a quick letter to Monroe boosting Zukofsky’s critical acumen:

Before leavin’ home yesterday I recd. 2 essays by Zukofsky. You really ought to get his Reznikof [sic]. = He is one of the very few people making any advance in criticism. = he ought to appear regularly in ‘Poetry’ … A prominent americ. homme de letters came to me last winter saying you had alienated every active poet in the U.S.—one ought not to be left undefended against such remarks. … Zuk has [a] definite critical gift that ought to be used. … You cd. get back into the ring if you wd. print a number containing [Zukofsky’s writing] … Must make one no. of Poet. different from another if you want to preserve life as distinct from mere continuity.3University of Chicago, Special Collections.

In the top left corner of Pound’s letter, Monroe added this brief summary of Pound’s letter: “Sug’d a Zukofsky number.” Shortly thereafter, Monroe took Pound up on his suggestion, writing to Zukofsky in October 13, 1930 and offering Zukofsky editorial control of an upcoming issue of her magazine. In her initial letter to Zukofsky, she emphasized some of her expectations for his editorial practice, telling him “I shall be disappointed, if you haven’t a ‘new group,’ as Ezra said.”4University of Chicago Special Collections.

[include some of the waffling and then some of confidence in his establishment of a group] At Pound’s urging, Zukofsky was given editorial power over a single issue of Harriet Monroe’s Poetry magazine, and, however awkwardly or unwillingly, used the issue to present “OBJECTIVISTS” 1931, which was published in February 1931. [more on the back story]

On October 14, 1930, shortly after getting the news that he’d be given an issue of Poetry to edit as he saw fit, Zukofsky wrote to his friend Rene Taupin telling him:

I need “book reviews” — I mean we can’t let her contribute any — and yours is the best I can get — So get busy. All material must be in by Dec. 20 — if you’re writing English verse send it on.

I’m afraid The Symposium has accepted the Am. Poetry 1920-1930, but they’re still trying to get me to emend a word here & there — they wanted, to begin with, to omit the Finale on Bill but I said all or nothing —

No compromises with

Louis [signature][as a postscript] My “new group” will probably include W.C.W. Rez. myself (maybe) E.E.Cs if I can get him, McAlmon, Geo. Oppen etc — maybe E.P. Know anybody else or can recommend anyone?5Taupin MSS, Lilly Library, Indiana University.

Within a week, Zukofsky had already formulated the rough contours of the issue, telling Taupin in a letter dated October 20:

Of course, I’ll select — or I’d be truly “couvert.” What I meant was that she’d print what I accept. Like all powerful men, I wanted an assurance of power.

We’ll say:

poetry: “Wms – “Alphabet of the Leaves” / Chas Reznikoff / Geo. Oppen / Rob’t McAlmon / L.Z. (A VII) / Maybe E.P. maybe Cummings / Maybe a half dozen people Pound knows of – / Maybe a half dozen lines by some of my friends

prose: My Rez: Sincerity & Object. which Pound has offered to cut — it will be interesting to see what he does to it / Mr. Yourself – André Salmon / maybe 2 lines by E.P — may ½ word by W.C.W. maybe a punctuation mark by E.E.C.6Taupin MSS, Lilly Library, Indiana University

While much has been made over Zukofsky’s reticence to be the standard-bearer of a movement and hemming and hawing over whether he had the “new group” Monroe was expecting, these very early letters to Taupin make visible how quickly Zukofsky had already formed a sense of the issue’s core contributors. Before he received the first of many advisory letters from Pound, Zukofsky already seemed confident that he wanted his issue to contain poetry Williams, Reznikoff, Oppen, McAlmon, and Zukofsky, plus work by Pound and Cummings if he could get it, along with a handful of contributions from people “Pound knows of” and work by “some of my friends.” This is more or less exactly what the issue ended up including, with Carl Rakosi, Howard Weeks, Basil Bunting, Norman Macleod, Emanuel Carnevali, Parker Tyler, Charles Henri Ford and Samuel Putnam comprising the former group and Joyce Hopkins/Irving Kaplan, Ted Hecht, Whittaker Chambers, Henry Zolinsky, Jesse Loewenthal, Martha Champion, and Taupin himself constituting the latter.

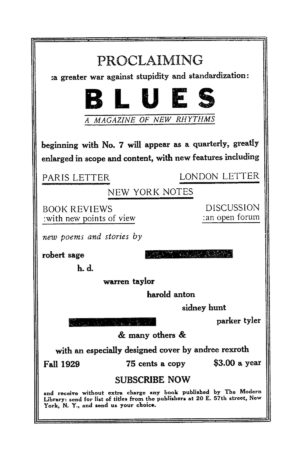

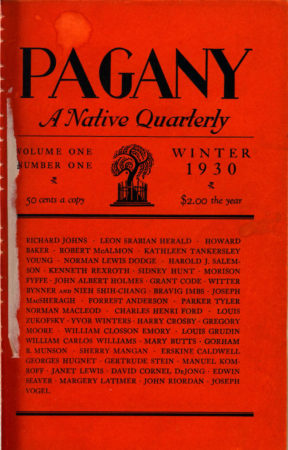

Of the four remaining writers to appear in the “Objectivists” issue, three of them: Kenneth Rexroth, Harry Roskolenko, and Richard Johns, were known to Zukofsky through their publication alongside him in Blues, the magazine Charles Henri Ford and Kathleen Tankersley Young had founded to continue the work of Pound’s The Exile. The only exception to this configuration was John Brooks Wheelwright, whose work Zukofsky had presumably read in Hound & Horn, and whose interest in Henry Adams, socialism, and revitalizing traditional forms likely all sounded sympathetic chords in Zukofsky.

This point is made explicit in a later letter from Zukofsky to Monroe, in which he reassured her

I shall probably—in fact, most certainly,—have more of a group than I thought. The contributions I have already—McAlmon, Rakosi, T.S. Hecht, Oppen, Williams, my own—tho never talked over by us together, go together. The Rakosi I received yesterday is excellent – the man has genius (I say that rarely) and he says he stopped writing five years ago—a curious case.7University of Chicago Special Collections.

These letters also help establish Zukofsky’s editorial independence from his mentor and benefactor. Pound’s editorial advice, crucially, didn’t begin to arrive until later in October. On October 24, Pound wrote to announce he had received the news from Monroe and to offer Zukofsky the beginning of what would be a torrential stream of advice as Zukofsky’s self-appointed “venerabilis parens”:

Wonners will neuHH cease. I have just recd. nooz from Harriet that she is puttin you at the wheel for the Spring cruise. … At any rate since it was a letter from donal mckenzie that smoked me up into writing Harriet that awoke in her nobl booZUMM the fire of enthusiasm that led her to let you aboard

I // wd. appreciate it if you wd. invite mckenzie to do one of the prose articles and state his convictions as forcibly as possibl . . . .

after which I see no reason why you shdnt. add a editorial note saying why you disagree.

Poetry has never had enUFF disagreement INSIDE its own wall.

need hardly to say that I am ready to be of anny assistance as I can. I do NOT think it wd. be well to insert my point of view. I shd. like you to consider mckenzie’s point of view and your own.

IF there is anyone whom you want to include and cant get directly, I might be of use in raking them in, but I dont want to nominate any one.

I shldnt. be in any hurry. Take your time and you can produce something that will DATE and will stand against Des Imagistes. …

The thing is to get out something as good as Des Imagistes by any bloody means at yr. disposal. (also to learn by my errors).

mckenzie might provide the conviction and enthusiasm (which you somewhat lack) and leave you to provide the good sense

I shd. in general be inclined to neglect anything already on file with “Poetry” waiting to be printed, and INVITE contribution from the active sperrits who wdnt. normally send their stuff to E. Erie St.

I can not GODDDDDAMMMMIT find mckenzie’s LIST of just men but am asking him to send it to you.

It mentioned <I think> McAlmon, Johns that edits Paganny, you, norman macleod at j’en oublie, several I did not know but all whom I cd. verify by ref/ to current periodicals seemed good.

(he also mentioned Dunning, not knowing that Cheever was ten years older than I am and already dead (in physical sense).

I cant see that you need be catholic or inclusive; / detach whatever seems to be the DRIVE / or driving force or expression of same . . . .

I shd. try to get a fairly homogenius number; emphasis on the progress made since 1912; concentrated drive, not attempt to show the extreme diversity; though it cd. be mentioned in yr. crit.

This also wd. make it a murkn number; excluding the so different English; … if you cover yourself with glory an’ honour, H.M. might even let Basil try his hand at showin what Briton can do. … or still also prejektin in to the future; Basil cd. crit. your number after the act, that wd. prob. be the best; you do yr. american damndest and then call in the furrin critic to spew forth his gall and tell what the Britons wd. LIKE to do that you aint done.

… thet wummun she nevuh trusted me lak she trusts you!!!8Pound/Zukofsky, 45-47.

[more from these letters]

Responding to Pound’s advice in a letter dated November 6, 1930, Zukofsky expressed clear reservations about the homogeneity of the writers he had gathered, emphasizing his own belief in particularities:

Seems to me I have no group but people who write or at least try to show signs of doing it … The only progress made since 1912—is or are several good poems, i.e. the only progress possible—& criteria are in your prose works. Don’t know (my issue) will have anything to do with homogeneity (damn it) but with examples of good writing.9Pound/Zukofsky, 65.

Later in the same letter, however, he would also insist:

I’ll have as good a “movement” as that of the premiers imagistes—point is Wm. C. W. of today is not what he was in 1913, neither are you if you’re willing to contribute—if I’m going to show what’s going on today, you’ll have to. The older generation is not the older generation if it’s alive & up—Can’t see why you shd. appear in the H[ound] & H[orn] alive with 3 Cantos & not show that you are the (younger) generation in “Poetry.” What’s age to do with verbal manifestation, what’s history to do with it … I want to show the poetry that’s being written today—whether the poets are of masturbating age or the fathers of families don’t matter. … Most of the men I choose will not be people who have been in touch with you. Satisfied?10Pound/Zukofsky, 67.

Apart from Zukofsky’s insistence on individuation and his illuminating choice of gendered collective noun (i.e. “most of the men I choose will not be people who have been in touch with you”), what’s most striking about this passage is his insistence that his issue would be concerned with the “poetry that’s being written today,” and his emphasis not on ages or generations but on poetry as something like a timeless or durable “verbal manifestation.” It’s not so much that Zukofsky didn’t understand the strategies of movement building and generations that Pound was insisting on as that he disagreed with them. This seems clearly understood by both men, and is a large part of why Pound wanted to pair Zukofsky with the more bombastic McKenzie (since he would “provide the conviction and enthusiasm (which you [meaning Zukofsky] somewhat lack)” and told Monroe that “[m]y only fear is that Mr. Zukofsky will be just too Goddam prewdent.”11The Letters of Ezra Pound, 1907-1941, 307.

Though Zukofsky stuck to his principles and largely presented the group in his own way, Pound’s insights were largely accurate. Following the issue’s appearance in February, the responses began to roll in, and nearly all of them were negative, ranging from hostility at one extreme to baffled confusion at the other. 12A January 16, 1931 letter from Zukofsky to Poetry magazine’s associate editor Morton Zabel begins “I gather from your letter that the Feb. issue is being attacked already. Who are the “attackers”—or should I not ask the question? No, it isn’t all objectification — perhaps very little of it is — but I think it is sincerity as defined in the editorial. Some objects, however, are tenuous — McAlmon’s poem, for instance, — for the sake of certain accents of speech a slow projectile gathering acceleration as it comes home?” (Letter to Zabel in University of Chicago Special Collections). The March 1931 issue of Poetry included “The Arrogance of Youth,” Monroe’s editorial response to Zukofsky’s issue expressing her dismay at Zukofsky’s summary dismissal of nearly all of the poetry published (in Poetry and elsewhere) over the previous few decades.13Monroe’s editorial can be read online at https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/browse?contentId=59518. In her editorial, Monroe also noted the strictness of what she termed Zukofsky’s “barbed-wire entanglements,” before ending on a more catholic, conciliatory note, offering a “glad hand to the iconoclasts” and stating that while Poetry “will try, in the future as in the past, to keep its head and its sanity,” she can “at least cheer … Zukofsky and his February friends … on. They may be headed for a short life, but it should certainly be a merry one.”14Poetry (March 1931), 333. Just as tellingly, citing difficulties that had arisen in the production of the issue as a result of Zukofsky’s distance from Chicago (he was less than 150 miles away in Madison), Monroe expressed reservations in a letter to Basil Bunting about their proceeding with plans to give Bunting editorial control of a British poetry issue to be organized along similar lines.15Pound had hoped that Zukofsky’s issue might be an ‘American’ issue, and he hoped to persuade Monroe to follow it up by allowing Basil Bunting to edit an ‘English’ issue, and René Taupin to edit a ‘French’ issue. While Monroe never again gave full editorial control of an entire issue of Poetry to anyone Pound had recommended, the February 1932 issue of Poetry was something of a compromise. Promoted as an “English Number,” it featured Bunting’s “English Poetry Today,” a review of contemporary verse in England that began with the claim that “There is no poetry in England, none with any relation to the life of the country, or of any considerable section of it,” and went on to savage just about everyone then publishing in Britain, with T.S. Eliot coming in for particular abuse (264). The poetry included also bore the mark of Bunting and Pound’s editorial preferences, as it included Bunting’s satirical poem “Fearful Symmetry” as well as work by Ford Madox Ford, J. J. Adams, and Joseph Gordon Macleod, all of whom Pound had previously praised.

In the April issue Monroe included an edited selection of letters from readers along with a reply from Zukofsky. Many readers seemed to be genuinely confused by Zukofsky’s prose statements. Stanley Burnshaw, then working as an advertising manager for the Hecht Company, wrote in to ask: “Is Objectivist poetry a programmed movement (such as the Imagists instituted), or is it a rationalization undertaken by writers of similar subjective predilections and tendencies[?] … Is there a copy of the program of the Objectivist group available?”1653. In his reply to Burnshaw, Zukofsky emphasized the fundamental individuality of the serious writer: “Interpretation differs between individuals and sometimes there are schools of poetry; i.e., there is agreement among individuals. But linguistic usage and the context of related words naturally influence an etiquette of interpretation (common to individuals, and, it has been said, “for an age”–though all kinds of people live in an “age”)” before both dodging and dismissing Burnshaw’s question, claiming: “To those interested in programmed movements “Objectivist” poetry will be a ‘programmed movement.’ The editor was not a pivot, the contributors did not rationalize about him together; out of appreciation for their sincerity of craft and occasional objectification he wrote the program of the February issue of Poetry” and brusquely recommending Burnshaw reread the other prose statements in the issue1756. In a letter to Morton Zabel written on February 19, 1931, Zukofsky detailed the responses he had sent to Burnshaw and Horace Gregory, telling him “One can’t give too much time to these things—let what’s clear speak for itself” and provided detailed responses to Zabel’s apparent criticism of McAlmon’s work (University of Chicago Special Collections).

About the only praise for the issue came from Ezra Pound, who sent a postcard claiming “this is a number I can show to my Friends. If you can do another eleven as lively you will put the mag. on its feet,” though Monroe tempered his enthusiasm with her deflating riposte: “Alas, we fear that would put it on its uppers!”18To be “on one’s uppers” was an idiomatic expression meaning to be impoverished (“uppers” was a slang term for shoes). The full exchange of correspondence published by Monroe in the April 1931 issue can be found online on the Poetry Foundation’s website: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/browse?volume=38&issue=1&page=65.

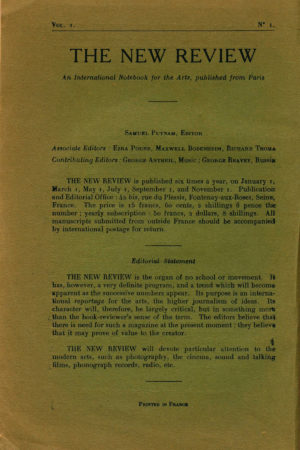

An “Objectivists” Anthology

Shortly after the appearance of his “OBJECTIVISTS” 1931 issue of Poetry, had Zukofsky begun to work on selecting and editing a larger collection of work to be published as an “Objectivists” anthology. Zukofsky appears to have believed, based on his correspondence with Ezra Pound, that the finished anthology would be published by Samuel Putnam, the Paris-based publisher of the magazine The New Review.19Zukofsky had written to Pound in April 1931: “O yes—try & persuade Putnam to come across with an “Objectivists” anthology ed. by me—and a volume of my woiks—I need prestige (Pound/Zukofsky, 97). The May-June-July 1931 issue of The New Review, which had been titled “The New Objectivism,” had included two sections of Zukofsky’s “A” as well as a lengthy editorial entitled “Black Arrow” in which Putnam praised the “Objectivists” issue of Poetry and described Zukofsky as “the best, the most important critic that I am able to think of in America.”20See New Review, 1: 2 (May-June-July 1931), 71-89. In October 1931, Zukofsky finished his edits for the anthology and sent a manuscript to Putnam, and the fourth issue of The New Review (published in Winter 1931-1932) included an announcement for An “Objectivist Anthology” to be edited by Zukofsky and published in Spring 1932 [shown at right].

An announcement of forthcoming publications from The New Review Editions published in the Winter 1931-1932 issue of The New Review. The first title listed is Zukofsky’s An “Objectivist Anthology.” Putnam ultimately did not publish the book, which was brought out instead by To, Publishers.

Unfortunately for Zukofsky, he had done the work entirely on speculation, without securing either a contract or payment for the anthology from Putnam, and late in 1931, Putnam began to ghost Zukofsky, leaving his letters unanswered. As the months ticked by without further word from Putnam, Zukofsky became increasingly anxious that Putnam would not publish the anthology. In February 1932, Zukofsky’s worst fears were confirmed when he received Putnam’s rejection.21According to Tom Sharp, Zukofsky wrote to Pound on 15 March 1932 chastising himself for sacrificing his money, time, and energy without a serious promise of publication, and announced that “he would no longer submit work unsolicited or without pay, especially for editors like Putnam,” though there would be several more cruel lessons for Zukofsky to learn about the poetry and publishing “biz” in the years to come. In May 1932, Pound informed Zukofsky that his association with The New Review had been ended: “Sam Puttenheim is drunk half the time/ over works the other two thirds / worries I shd/ think about his health (which is the worst known to man) the remaining fifth/ His last issue New Rev. inexcusable on any other base/ass. Sorry!///he’za sympathetic kuss/ Have said faretheewell to his orgum.”22Pound/Zukofsky, 126. After his publishing plans with Putnam collapsed, Zukofsky persuaded the Oppens to bring out the anthology, and in August 1932 the Oppen’s oversaw its printing in Dijon, France as To, Publishers’ final publication.

An “Objectivists” Anthology was divided into three sections: lyric (section 1), epic (section 2), and collaborations (section 3) and contained work by 15 contributors, eight of whom also had also appeared in the “Objectivists” 1931 issue of Poetry.23The eight authors included in both publications were: Bunting, Rakosi, Reznikoff, Oppen, Williams, Zukofsky, Robert McAlmon, and Kenneth Rexroth. The six writers who appeared in the anthology but not in Poetry were Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot, both well-known enough not to need an introduction here; Mary Butts (1890-1937), a English modernist writer who was well-known to Ezra Pound who had previously been married to the poet and publisher John Rodker; Frances Fletcher, a teacher and graduate of Vassar College who had published two slim volumes of poetry in 1925 and 1926; Forrest Anderson, a San Francisco native who had published poems in Blues, Pagany, Tambour, and transition; and R.B.N. Warriston, an acquaintance of Zukofsky’s who lived in White Plains, New York. The anthology also included a collaboration between Zukofsky and Jerry Reisman, his friend and former student at Stuyvesant High School. More detailed biographies of each of these contributors is available in The Lives section of this site.

As with the “Objectivists” issue of Poetry, Zukofsky’s anthology failed to make the impact he had hoped for. He told Zabel in September 1932

I sent out about 30 “Objectivists” Anthology for review, and not a murmur, not even a cardiac murmur in reply, or an announcement or anything. I hope at least that “poetry” will not let the book go stillborn. You received your copy at “Poetry”‘s office? What do you think of it?24University of Chicago Special Collections.

Zabel’s reply indicated that they had not received their copy, which led to Zukofsky sending two additional review copies to the magazine in January, suggesting to Harriet Monroe that perhaps it might be assigned to Marianne Moore. Instead, the anthology was assigned to Morris Schappes, who wrote a hostile review which appeared in the March 1933 issue and to which Zukofsky’s reply was printed in May 1933.25See https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/browse?contentId=59581.

Book Publishing Efforts, Real and Imagined

In addition to their involvement in a network of little magazines published during the era (discussed below), several members of this loose alliance were also united in a number of schemes to form and operate a press which would issue book-length collections. Two of these proposed publishing schemes, To, Publishers and The Objectivist Press, succeeded in issuing books by various “Objectivist”-affiliated writers in the years immediately following the appearance of the February 1931 issue of Poetry.

To, Publishers

Upon his twenty-first birthday in April 1929, George Oppen had come into a small inheritance from his deceased mother’s estate. It was with this money as the necessary starting capital that the Oppens founded, with Louis Zukofsky, To, Publishers in late 1931, though the idea for the press appears to have been discussed and agreed upon well before this time. The name appears to have been Zukofsky’s idea, and is certainly of a kind with his famous preference for “little words” (like “The,” “A”, W.E., etc.).26Zukofsky wrote in “For My Son When He Can Read”: “The poet wonders why so many today have raised up the word ‘myth,’ finding the lack of so-called ‘myths’ in our time a crisis the poet must overcome or die from, as it were, having become too radioactive, when instead a case can be made out for the poet giving some of his life to the use of the words the and a: both of which are weighted with as much epos and historical destiny as one man can perhaps resolve. Those who do not believe this are too sure that the little words mean nothing among so many other words” (Prepositions, 10). Zukofsky glossed the firm’s name in a letter to Morton Zabel:

Strange to say we wanted a name to sink into the public mind & To promises to be as good as any. Let alone direction, if one wants to be cordial — the dative of the noun To (the name of our business) means to To or for To. I’ve heard allegiance is necessary in business. Mm … if I were only Mussolini.27University of Chicago Special Collections

In light of his later interest in acronyms for publishing ventures (Writers Extant or W.E. Publishers), another possible reading of the company’s name is as an acronym for The Objectivists, though I have not found any documentary evidence that makes this intention explicit.

In the summer of 1930, Zukofsky travelled to Berkeley, California where he spent a few weeks staying with his Columbia friend Irving Kaplan. Sometime after Zukofsky left the Bay Area to take up his teaching position in Wisconsin, the Oppens left San Francisco for France.28The historical record is somewhat confused on this point. Mary Oppen seems to suggest in her memoirs that they left for Europe in 1929 or 1930, but the ship manifest detailing the Oppen’s return to the United States in June 1933 indicates that their passports were issued in March 1931. After their arrival in Le Havre, the Oppens purchased a horse cart and spent some months traveling across the French countryside, stopping in Paris, Marseilles, and Cannes before settling in Le Beausset, a small village in the south of France near Toulon. The Oppens established To late in 1931, paying Zukofsky $100 a month to act as the firm’s managing editor from New York City.29This money helped soften the blow of giving up his teaching position in Madison, for which Zukofsky had been paid $1000 during the 1930-1931 academic year and which he had been offered a renewal the following year. On October 15, 1931, Zukofsky wrote to Pound: “Geo Oppen is planning a publishing firm—To, Publishers, and I’m the edtr. We’ll probably begin with Bill’s collected prose—or at least—Bill’s been spoken to” (Qtd. in Pound/Zukofsky, 101).

On December 10, 1931, Zukofsky shared To’s publishing plans with Ezra Pound, indicating that they expected to print a book every two months, and providing this list for their first year’s publications:

- Bill Walrus [William Carlos Williams].

- E[zra].P[ound]. Section I.

- If Oppen agrees—Tozzi/Buntn.30Pound had suggested in a letter the previous month that Bunting might translate the Italian poet Federigo Tozzi’s novel Tre croci (written in 1918 and published in just before his death of influenza and pneumonia in 1920). Bunting never produced this translation.

only objection: we may have to pay Tozzi—is he alive?—& we cdn’t afford to pay both Bunting & Tozzi—But you write Oppen & see what he says. No, I don’t think we propose to be purely amurikun. In fact, we expect you to be on lookout for foreign material and make suggestions all the time.- Possibly L[ouis].Z[ukofsky].

- Reznikoff. (probably)

- E.P. (2nd section).

Bob McA—cd. be taken care of the second year. We don’t want the same homocide squad allee time. By that time he shd. be rejected by everyone else & (have) polished off his Politics of Existence31This McAlmon book was never finished and remained unpublished at his death in 1956. A undated draft of the manuscript with a 1952 letter explaining the project of the novel can be found among his papers in Yale’s Beinecke Library. which has fine things in it—what I’ve seen—but needs to be cut (& I mean cut). Not just circumcised.32Pound/Zukofsky, 117

On December 28, 1931, Zukofsky sent a letter to Morton Zabel in Chicago on To Publishers’ letterhead, telling Zabel the firm’s name was to be pronounced “like the preposition. The noun wd. indicate the dative,” and explaining that it was a

new publishing venture: Geo. Oppen, publisher, L.Z. editor. Books to printed in France, brochure, 50¢ each. At least six a year. Present list:

- Wm. C. Wms – A Novelette & other Prose

- Section I – Ezra’s Prolegomena (Collected Prose)

- (Probably) Bunting’s Translation of Tre Croce by Tozzi

- (If I’m convinced) something by L.Z

- (Probably) Reznikoff – My Country ‘Tis of Thee

- E.P. Section II Collected Prose (there’ll be about six of these E.P.’s – & ultimate folio)

7,8, etc Rakosi, Rexroth etc etc33University of Chicago Special Collections.

Sometime in late 1931 or early 1932, Oppen also sent Pound a letter from Le Beausset describing To, Publishers as

A new press, printing in France. Publishes chiefly brochures to sell for 8 Francs. Its program for the year includes: Prolegomena (collected prose) of Ezra Pound (to be published as a series); A Novelette and Other Prose, by William Carlos Williams; a novel by Charles Reznikoff; poems by Louis Zukofsky.

and a translation of34Ezra Pound Papers, Beinecke (Yale), YCAL MSS 43, Box 38, Folder 1613

As their proposed list of publications makes clear, To, Publishers was nothing if not an “Objectivist” publishing venture: funded and operated from France by the Oppens, it employed Zukofsky as the managing editor, and in addition to An ‘Objectivists’ Anthology published (or planned to publish) work by Williams, Pound, Zukofsky, Reznikoff, Oppen, Bunting, Rakosi, and Rexroth.

As was the case with so many other depression-era publication schemes, To’s ambitions far exceeded their actual capabilities. In February 1932, the Oppens oversaw the publication William Carlos Williams’ A Novelette and Other Prose, which was followed in June 1932 by Ezra Pound’s Prolegomena 1: How to Read, Followed by The Spirit of Romance, Part 1, both of which were produced as paperbacks (in pamphlet form) by a print shop in Toulon. The press was immediately beset by a number of problems, however, including a number of difficulties in the production and import processes. Some of these difficulties can be seen in a series of letters Zukofsky sent to Morton Daubel. On January 26, 1932, Zukofsky sent a postcard noting that the price of the publications had been raised to 75¢, to accommodate both a 25% customs duty and increased production costs, and he followed this note up in March of that year by writing

The books haven’t arrived from France yet. The French printer doesn’t read English, & Oppen has had to read proof at least seven times, so far. Incidentally, please do not mention Oppen’s (the owner’s) and my (the editor’s) name in your extenso notes of To in Poetry. Thanks for the trouble.35University of Chicago Special Collections

According to Mary Oppen:

When we shipped the books of To Publishers from France to Louis in New York, he found that he could only get the books by paying a duty. Customs declared them to be magazines, not books, but a loophole existed—if we wrapped them in bundles of twenty-five or less they could come in duty-free. This entailed numerous trips by us and by Louis to the Post Office. … neither of us [meaning George & Mary] understood anything of business, and neither did Louis. It is perhaps surprising that we actually did get books printed. Financially we had taken on too big a burden; we could not support ourselves, Louis, and the printing and publishing of the books unless at least a small amount of money came back to us. And no money came back to us.36Meaning a Life, 131.

While some of the details in Mary Oppen’s recollections may have been warped slightly by the passage of time, the fundamentals appear accurate. The company’s financial viability was probably hindered some of Zukofsky’s personal limitations; while an undeniably gifted editor, he was, by his own admission, never a very skilled (or tremendously interested) marketer or salesman. He was described as being an “indifferent, sometimes negligent bookseller” when working at his brother Morris’ Greenwich Village bookstore in the late 1920s;37After Whittaker Chambers was fired from his job at the New York Public Library in April 1927 when dozens of “missing” books were found in his coat locker, Zukofsky found him a job working with him at his brothers bookshop. Chambers’ biographer Sam Tanenhaus writes: “Chambers and Louis were supposed to help customers at noon, when the regular staff broke for lunch, but were indifferent, sometimes negligent booksellers, seldom stirring from their seats. Henry Zolinsky, a frequent visitor, once put them to a test, asking for a volume. When Chambers and Zukofsky assured him it was not to be found, Zolinsky walked over to the shelves and pulled down the book himself” (Whittaker Chambers: A Biography, 56-57). Pound wrote about hearing of others’ lack of confidence in his business sense as early as 1931;38Barry Ahearn quotes a November 29, 1931 letter in which Pound informs Zukofsky that “[René] Taupin has filled Basil [Bunting] with firm belief in yr. utter incapacity to transact ANY business operation” (Pound/Zukofsky, 121). and sales records of each of the publishing ventures he was involved with did little to inspire confidence in his ability to arouse public interest. Whatever the precise reason, sales of To’s first volumes lagged far behind Zukofsky and the Oppens early hopes. In December 1931, when Zukofsky was finalize the financial arrangements surrounding To’s publication of How to Read, he had quoted a letter from Oppen which referenced their willingness to “pay twenty percent on copies sold over the number (about 3000) necessary to pay 100 dollars on a ten percent royalty. That comes to the same thing as my original suggestion to you, except that it gives us our clear (almost) profit on the copies sold from 1600 (which is necessary to break even) to 3000. Which profit we’ll probably have use for it we ever get it.”39Pound/Zukofsky, 114-115. In May 1933, Zukofsky gave Pound a report on total sales of To’s three publications, a far cry from the 1600 copies Oppen had earlier asserted they would need just to “break even”:

Since you ask: Bruce Humphries have brought [sic] to date from To

25-W.C.W. [Williams’ A Novelette]

75 – H.T.R. [Pound’s How to Read]

71 – “Obj” [An “Objectivists” Anthology]To’s total sales in U.S.A.:

150 – W.C.W. (Bill bought 50)

109- H.T.R.

130- Obj.In Europe as far as I know

12-W.C.W.

28- H.T.R.

10-Obj.40The Selected Letters of Louis Zukofsky, 102.

With dismal sales and the difficulties already described, the Oppens quickly realized that they were on pace to exhaust their limited capital. In August of 1932, George Oppen informed Zukofsky that he would be unable to continue operating the publishing company (or pay Zukofsky to act as its managing editor) beyond the end of the year, and that they would have to scrap nearly all of their remaining plans for publication. Zukofsky wrote to Pound on August 8, 1932: “Latest news from O[ppen]:—”Can’t continue To.” Which means my salary goes as well when the year is up—& will probably be reduced to $50 (if George can spare that much) a month, while it lasts. “The year is up”—may be this Sept. 1932—I’m not sure when my year started, since Buddy [George’s nickname] and I made no formal legal arrangements.”41Pound/Zukofsky, 132. Zukofsky’s salary was in fact reduced to $50 in August, and discontinued altogether after October 1932 (Zukofsky, Letters to Pound, 8 October 1932, Yale).

The publication of An “Objectivists” Anthology in August was the press’s final gasp, and once it was printed, from Dijon rather than Le Beausset, which the Oppens had already departed, the company’s was disbanded. To’s dissolution was confirmed in a letter from Zukofsky to Zabel on September 12, 1932:

N.Y. has become about as impossible as Madison was 2 years ago.

My “projects” — or maybe they’re not mine — don’t go. To has had to postpone publishing indefinitely. With postponement goes my salary. I don’t suppose you know of a job for me, but if you hear —42University of Chicago Special Collections.

Writers Extant

Chastened but not wholly discouraged by the failure of To Publishers and the loss of his monthly editor’s salary, Zukofsky’s next scheme was a proposed writers’ union to be called Writers Extant with a publishing arm to be called W.E., Publishers. Early in 1933, Zukofsky circulated a detailed prospectus for the idea among several friends, including both Pound and Williams, asking for their feedback and support. In a letter to Ezra Pound, Zukofsky indicated that the editorial board would be comprised of Tibor Serly, René Taupin, and himself, and its members would include Reznikoff and Williams, and possibly Rexroth, McAlmon, Marianne Moore, Mina Loy, Wallace Stevens, and others.43Qtd. in Sharp’s dissertation: http://sharpgiving.com/Objectivists/sections/22.history.html?visited=1#22history-51, Zukofsky, Letter to Pound, 17 April 1933, Yale and referenced in Pound/Zukofsky, 141-142. In early April 1933, Williams sent an initial reply, which was decidedly negative:

What the hell can I say about Writers Extant? I don’t see how it can be done. I think your prospectus is too complex. Where in hell is one to begin?

It’s all very well to name off twenty or more names of those you’d like to see members of such an organization but can you get them and can you keep them and can you manage them when you have them? I doubt it very much.

Personally I could at a pinch give up a couple of hundred dollars, but why? For two hundred dollars I could in all probability get my poems published and although that is a most selfish viewpoint yet it <is> one which must have weight with me since a sum of that sort is not easy for me to detach from my ordinary expenses. And unless I gave it I wouldn’t take a thing from the organization.

It is possible that we might get a book that would sell and so bring us in a profit. But don’t imagine for one minute that if some book were profitable it wouldn’t be taken away from us damned quick by the author or the firm to which he would sell out his rights.44The Correspondence of William Carlos Williams and Louis Zukofsky, 154.

Williams’ next letter, sent on May 6, was more conciliatory:

Having thought (waited!) doubtfully with your “Writers Extant” in mind I have come to the conclusion that there’s no other way out of our difficulties. It is basically the only way for us to proceed. BUT I do not think we have as yet hit upon either the correct name for the venture nor upon the proper method or procedure.

You have made a start and the motion is not lost. We are all searching for the phraseology. Part of the next step and it may take some time to develop it, come what may, is for you to see the men involved, personally. It will not be until after that that a program can be put down on paper. When you have done this (supposing for the moment that you are the permanent secretary indicated in your project) and after you have seen certain theoretical scripts, including my White Mule. Then we can band together, publish one book, the best we can find, and then, with some solid ground under our feet and snarl in our voices we can begin. LAST will come what is written down as a contract – after we have had some experience. Everything else must be tentative up to that time.45The Correspondence of William Carlos Williams and Louis Zukofsky, 155.

Along with that letter, Williams also included his own revised and severely abbreviated version of Zukofsky’s lengthy prospectus which he instructed him to show to Tibor Serly:

The Writers Publishers, Inc.

1. Membership in the group is limited to those writers who have in actual possession an available and complete book manuscript of high quality which is unacceptable to the usual publisher.

2. Manuscripts to be published by the group are to be selected (with advice) by a Director who shall be elected by a majority of the group members for the term of one year.

3. The business end of the group activities will be under the direction of a paid Secretary-Treasurer, under bond, who shall occupy the office indefinitely, or until removed by a two thirds vote of the existing membership at any time.

4. Initial funds are to be contributed by the charter members as may be agreed upon, to be added to later as the business of the group may prove profitable.

5. The first membership will be made up of a selected, voluntary group who by a majority vote, after the first requisite is satisfied, will add to their numbers from time to time.

6. Resignation from the group may take place at the discretion of the member by which he is absolved from further financial responsibility at the same time relinquishing any claim he has had upon the group’s resources.

7. Dissolution of the group as an organization will be conditional upon an equal distribution among the members of all funds and other rights enjoyed by the group under its incorporation.

8. Further additions to these rules will be made from time to time.46The Correspondence of William Carlos Williams and Louis Zukofsky, 156-157.

Williams urged that any revision be kept to no more than “2 pages in all” and indicated that “a few paragraphs may be added: Reznikoff can take care of a proper arrangement of the items.”47The Correspondence of William Carlos Williams and Louis Zukofsky, 156. Zukofsky forwarded Williams’ revisions to his prospectus to Pound within the week, urging Pound to take his own turn at revising them:

Continuin’ with organization—objection has been raised to “exclusiveness” of trade name. The Writers Publishers, Inc. has been suggested instead—& I enclose a copy of Bill’s “revision” of the prospectus. I don’t think he gets the real purpose of the original prospectus. But maybe you can do better in an idle moment. I mean tho his draft wd seem to be more business-like than mine he doesn’t see how he’s trapped himself again in the “highbrow licherary circle of viciousness.” Fer gord’s sakez, you don’t think I wrote all the detail of that prospectus—the Organization section especially—without for a moment having my tongue in my cheek! But the serious intent of the prospectus which makes it a thing not merely of this administration (an attempt to work with the dead), but at least a working chance that shd. fit in with the “new” economy when people begin to realize it—and they’ll have to—is in the prospectus, I mean L.Z.’s. No use backsliding, whatever the “difficulties ” of “style.” And if you’re afraid that “the idea is no good until L.Z. starts trying to write simple readable prose”—you write to letters to edtrs. now, you can write declarations in the future as of the Board of Writers Pubs. And L.Z. doesn’t intend to sit down to write 4 pg. Prospectii in the future. When the time comes he’ll find it more simple to use the technique of advertising, and say: Prof. So & So is still going to the stool, ethically. Messrs. Splinters and Plate persist in cutting the razor of morality.48The Selected Letters of Louis Zukofsky, 98-100.

While Pound did not appear to have attempted a revision, the proposal remained very much on Williams’ mind, as he wrote Zukofsky twice more in May to express his concerns about their proposal. His first letter, dated May 24, 1933, read:

I’ve tormented my soul long enough over our Writer-Publisher proposal: I think it’s no go and we should give it up. As far as you personally are concerned I think it would be an excellent thing for you to get to see Pound this summer. I’ll be glad to contribute my bit to assist you as agreed with Serly. I’ll believe we’d all derive some benefit from it by clarifying our present more than a little muddled thinking. Go and take a look. In the fall we can appraise the situation again if we want to.

And don’t forget that with every advantage in their favor large publishing houses are going broke. While even such a venture as Angel Flores’ Dragon Press has cost its sponsor two or three thousand dollars which he’ll never see again. It can’t be done today. Pound said it over and over again in his letter. We’ve got to heed such evidence.

The only possible way out of our difficulties, aside from hoping against hope, would be to print a series of six books at our own expense and then give someone like Harcourt, Brace 15% to market them – as others have done before us. But could we find six saleable new books? I doubt it. And even if we could find them, where would the next six come from? No, I can’t see it.49The Correspondence of William Carlos Williams and Louis Zukofsky, 158.

A week later, Williams wrote again:

It means this: I saw [Nathanael] West and <he> would have nothing to do with a self publishing venture. Quite correctly I think, he pointed out that no book should be self-published until it had been the rounds of all the commercial publishers. This would take a year. And if all of them turned it down you could be reasonably sure that it would not sell fifty copies under any circumstances. We should simply lose our money.

Besides, there are not twelve books in the country that would be available for our uses.

As for Josephine Herbst: she is about to become a successful author. Under those circumstances I refuse point blank to approach her. What for? To ask her for money? Never. To ask her for a script? Insane.

[Wallace] Stevens is under contract to Knopf.

It’s simply an impossible situation.50The Correspondence of William Carlos Williams and Louis Zukofsky, 159.

And that is more or less where things stood when in June when the Oppens returned from France (they arrived in New York City on June 7) and Zukofsky left on his long-awaited tour of Europe. On this trip, financed largely by Pound, Williams, and others of Zukofsky’s friends, Zukofsky met with Tibor Serly (in Budapest), René Taupin (in Paris), and Pound and Bunting (at Rapallo). Following his return to New York City at the end of the summer, Zukofsky made another push, arranging a meeting to discuss the launch of a collaborative publishing venture.

The Objectivist Press

This meeting was held on September 24, 1933 at the Oppens’ Brooklyn apartment at 214 Columbia Heights, and was attended by Zukofsky, Williams, Reznikoff, and the Oppens. At this meeting, the group established an advisory board (consisting of Williams and Pound with Zukofsky to serve as the executive secretary), made a tentative publishing list, and drew up a plan to request subscriptions. A letter from Williams to Zukofsky dated October 2, 1933 included his synopsis of what they had discussed:

Writers-Publishers to be incorporated:

- A possible list of subscribers to 1 book of poems to be circularized and approached by whatever means possible. The book to sell at $2 and to be the most saleable we can find.

- This book to be published on the basis of whatever advance subscriptions are obtained.

- The proceeds, if any, from this sale to be divided, 60% to the author, 40% to the group which 40% is to be used to publish book #2 and to pay the Executive Secretary who will be the sole officer of the group.

- On this basis books are to be continued to be printed and sold as often and for as long a time as practicable.

Notes: When the first book is advertised it will be put forward as one of a series of four which will all be published and offered, separately, for subscription during the first year.

The original suggestion of E[zra].P[ound]. to be rewritten to conform to this plan.

As a feature of the plan distinguished (?) modernists of the day will write introductory pages to these books – their names (with consent) to be given out when the first notices appear: such names as Marion [sic] Moore, T.S. Eliot, Wallace Stevens, etc etc. This in effect will be a sponsoring Committee without putting too much of a burden on names.

Harriet Monroe and Poetry to be approached from the first with intent to get as much backing from that source as being the official (?) poetry organization in U.S.

Mr. Zukofsky be named to Executive-Secretary etc. etc. with power to keep records, see individuals, arrange for publishing, correct proofs ? ? ? select format, wrote letters, devise lists, compose advertising matter, push sales, etc, etc — God help him!51The Correspondence of William Carlos Williams and Louis Zukofsky, 165-166.

Williams also included his enthusiasm for the plan, telling Zukofsky that “That scheme as outlined has the earmarks of feasibility, the best yet! I am grateful to you for your vision and persistence, I’ll back you in every way possible. To begin with you may count on me for the first hundred toward my book. I’d pay it all but I decided long ago not to. And I’ll go after Marianne and Wallace Stevens at once.”52The Correspondence of William Carlos Williams and Louis Zukofsky, 165.

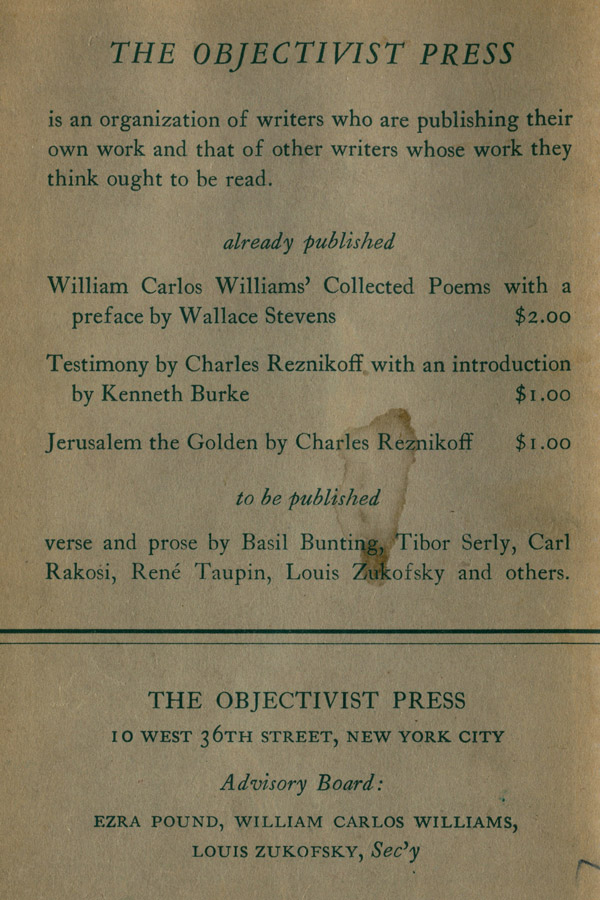

Over the next few weeks, the group considered other names for their venture (including two of Williams’ suggestions: Writers-Publishers and Cooperative Publishers), ultimately settling on the singular form of The Objectivists Press.53On October 23, 1933, Zukofsky had written to Pound asking him to join himself, Williams, and Reznikoff as a partner in The Objectivists Press (a spelling he also included in a follow-up query to Pound dated October 29), but by November they had dropped the plural and reverted to The Objectivist Press, which is the name under which all their subsequent books were published. They also adopted a simple statement of purpose, proposed by Reznikoff, which was printed on the books’ dust wrapper: “The Objectivist Press is an organization of writers who are publishing their own work and that of other writers whose work they think ought to be read.”

The press launched itself into existence in January 1934 through the publication of Williams’ Collected Poems 1921-1931, printed in an initial edition of 500 by J.J. Little and Ives Company, in New York, and was sold by subscription. As the first book issued by the Objectivist Press, the book’s dust jacket prominently featured the press’ name and address,5410 West 36th Street, two blocks northeast of the Empire State Building in midtown Manhattan. as well as praise from Marianne Moore, Ezra Pound, and René Taupin. Williams’ book, which featured a preface written by Wallace Stevens, was a modest success, both critically and commercially; it was reviewed by Charles Poore in the New York Times Book Review in February, and nearly sold out its initial edition at $2 a copy, netting the press a small profit.

The back cover of the dust jacket for George Oppen’s Discrete Series (1934), with publication information for The Objectivist Press.

The press also published Reznikoff’s Testimony (a prose work which featured an introduction by Kenneth Burke, Williams’ friend and former editor of The Dial) that same month, and followed the publication of these two books in January with two volumes of poetry in March: George Oppen’s Discrete Series (which included an introduction by Ezra Pound) and Reznikoff’s Jerusalem the Golden. The back cover of the dust jacket for Oppen’s book (shown at right) is particularly illuminating in regards to how The Objectivist Press presented itself: it included the press’ mission statement and advisory board, listed their three already accomplished publications and announced their plans to bring out “verse and prose by Basil Bunting, Tibor Serly, Carl Rakosi, René Taupin, Louis Zukofsky and others.”55Williams shared his first year’s publication suggestions with Zukofsky in a letter written sometime late in 1933: “The names I’d suggest for the first year would be my own (not because I wish it so but because the general opinion seems to be that my book would be a good one to start with) the Zukofsky, Bunting, Rakosi. I believe we’ll have our hands full trying to get a book out every 3 months” (The Correspondence of William Carlos Williams and Louis Zukofsky, 166-167).

While the venture had begun with Zukofsky’s lofty ambitions and a lengthy list of works they intended to publish, the Objectivist Press did not prove to be long-lived, collapsing as a functional cooperative within a year. Fissures in the organization had appeared almost immediately, in fact, with Zukofsky writing privately to Pound of his exhaustion and the possibility of his leaving the press as early as April 12, 1934:

have been sick myself tho working on a C.W.A. [Civil Works Administration] job, now transferred to Dep’t of Pub. Welfare, N.Y.C.—6 hrs of continual insult to the intelligence, 2 hrs travel, 1 hr. “lunch.” 9 hrs a day, & then 1-3 hrs of the Obj. Press when I get home. Municipal salary $19 a week. Other salary $0. Which leaves very little time for writing, but I’ve done some. … May have to resign Sec’y of Obj. Press if burden of work continues, & the effort spent on the press does not repay in the way of enough sales allowing us to continue. It’s a ha-a-rd job, & besides there may be necessity for direct action in another field (in add. to poetry)—and aside from publishing—I’m afraid there is now only I’m holding back. You were right last summer about staying clear of becoming an office boy–besides peeple dun’t appreciate.56Pound/Zukofsky, 156-157.

By the end of the year, the press had issued just one additional book after Oppen’s Discrete Series, Reznikoff’s In Memoriam: 1933 and was no longer operating as a functional collective. A number of things contributed to the press’ demise: Zukofsky and Oppen quarreled57In Meaning a Life, Mary Oppen relates one version of the story: “Walking with Louis when Discrete Series was in manuscript, George was discussing it with him before showing it to anyone else. Louis turned and with a quizzical expression asked George, “Do you prefer your poetry to mine?” “Yes,” answered George, and the friendship was at a breaking point” (Meaning a Life, 145). This elliptical account leaves much unsaid, my own view of the split was that it was probably exacerbated by the fact the Oppen, who had money, was publishing his book of poems (and with an introduction from Pound), while Zukofsky, who did not have money, was not. “Do you prefer your poetry to mine?” may have been the Oppens recasting of a request by Zukofsky to underwrite the publication of his work and George’s refusal to do so. Elsewhere in her account, Mary Oppen tells other stories that indicate class-based stressors in the relationship between Zukofsky and her husband (208-209). and the Oppens traveled to Mexico in the summer of 1934, joining the Communist Party and devoting their energies to what Zukofsky referred to in the letter just cited as “direct action in another field” as organizers for the Workers Alliance soon after their return to the United States;58In Meaning a Life, Mary Oppen dates their decision to join the party to Winter 1935, and the context of her statement lends itself better to the assumption that she meant January or February of that year rather November or December. Williams’ plan to develop an opera with Zukofsky’s friend Tibor Serly fell apart, damaging Williams’ friendship with Zukofsky; and Zukofsky resigned as the press’ secretary. The relationship between Williams, Zukofsky, and the Oppens appears to have been strained by late 1934; Zukofsky wrote to Pound in November 1934 asking about the possibility of Faber & Faber printing his poem “Mantis,” and again in February 1935 asking explicitly for help in getting his 55 Poems manuscript published in England:

You can, if it won’t hurt your own name, try and get me published with Faber & Faber. Serly off to Europe with my final arrangement and additions to 55 Poems–a most commendable typescript for you to look at. Time fucks it, and if I keep my MSS. in my drawer or my drawers, I might as well shut up altogether. … Pleased also with your choice of my work for the same ampholgy [the Spring-Summer issue of Westminster Magazine]. Enclosure should have probably gone into Westminster, if it reached you in time. No place now to print it in ‘Murka. Do you think Mr. Eliot would see it? And Random House continues to print beeyutiful volumes of shit by Spender and Auden.

If you consent, think it opportune etc, to try my 55 on Faber & Faber, you need not worry about an introduction—I don’t want it—you can write a blurb for the dust-proof jacket if it jets out of you.

Noo Yok at a standstill. Haven’t heart from Bill Willyums in moneths.59Pound/Zukofsky, 160-161.

Further confirmation of the timing of the split can be found in a letter from Williams to Zukofsky in March 1935 which indicates both that Williams hadn’t heard from Zukofsky for roughly 6 months and that he had heard that Zukofsky and the Oppens had fallen out.60See The Correspondence of William Carlos Williams and Louis Zukofsky, 212. Zukofsky’s inquiries with Pound about publication opportunities can probably be read as signs that the Objectivist Press had failed, since Zukofsky had clearly intended for the press he had worked so hard to establish and for which he was serving as the secretary to publish his own work.

The various schisms between Zukofsky, Williams, Pound, and the Oppens and their departures from or disillusionments with the press left Reznikoff alone among the collective’s founding members. Reznikoff, who had both trained as a lawyer and was the only member of the group to own, in the form of a hand-operated printing press, the literal means of production, also retained the copyright for the press. Following Reznikoff’s solo publication of his collection Separate Way under the imprint in 1936, the Objectivist Press imprint remained dormant until Louis and Celia requested its use from Reznikoff for their private publication of Louis’ A Test of Poetry in 1948.61See Mark Scroggins’ “The Objectivists and their Publications,” on Jeffrey Twitchell-Waas’ Z-Site.

The collapse of The Objectivist Press also led Williams to seek other publishers for his poetry; he turned first to Ronald Lane Latimer’s Alcestis Press, publishing his collections An Early Martyr and Other Poems and Adam & Eve & the City with Latimer in 1935 and 1936, before James Laughlin’s New Directions Press became his regular publisher starting with the publication of his Complete Collected Poems in 1938. Because he had lacked the capital to finance the publication of his 55 Poems through either To, Publishers or The Objectivist Press, Zukofsky’s manuscript was among the last of their proposed publications to appear in print, as it was not published until 1941, when the James. A Decker Press of Prairie City, Illinois, brought it out in a handsome hardcover edition.62Decker’s press had previously volumes of poetry by several other contemporary poets, including Zukofsky’s friends and fellow “Objectivists” Norman Macleod, Charles Henri Ford, and Harry Roskolenko.

It is against this backdrop of frustration that we Zukofsky’s oft-quoted contributor’s note in the Spring 1934 Westminster magazine “disclaim[ing] leadership of any movement putatively literary or objectionist” appeared.63”Notes on Contributors,” Westminster Magazine 23:1 (Spring 1934), 6. What is less-commonly observed is that this note accompanied the second of two installments from Zukofsky’s “The Writing of Guillaume Apollinaire.” The first, published in the Winter 1933 issue, had included the following contributor’s note: “MR ZUKOFSKY is the leader of Objectivism in America; his work has appeared in the better American and European magazines.” It’s certainly plausible to see Zukofsky’s subsequent statement as emerging largely out of frustration at this gross biographical mischaracterization.

Rather than seeing this claim as evidence that he had never intended a group, a more plausible reading of Zukofsky’s disavowal would require giving more than usual attention to what Zukofsky intended by the words “movement,” “literary,” and “objectionist.” If we read the Objectivists’ concerns as primarily oriented towards reliable access to publication rather than the achievement of a particular aesthetic or political program, much of the apparent conflict in Zukofsky’s actions and this seemingly defensive statement can be resolved. When it came to the problem of publication, Zukofsky devoted a great deal of energy to trying to form and sustain two publishing collectives for which he had provided the central organizing force and served as editor. Yes, the “Objectivists” may well have begun as a contrivance conjured up to satisfy Harriet Monroe’s desire that Zukofsky present a “new group” in Poetry, but it is equally true that Zukofsky named and defined the group himself and further chose to perpetuate the “Objectivists” name for several years after their first appearance.

A May 11, 1935 letter to Pound is perhaps Zukofsky’s most explicit statement on what he took as the lessons of the failure of his publishing efforts:

But you needn‘t tell me that “All good books are Blocked by the present fahrty system”—why ‘n hell do you think I asked your aid? Between the New Masses crowd who can’t get the distinction that yr. poetry is one thing & yr. economics another, & yr. unwillingness to even look at my work to see what it says because I won’t embrace Social Credit, these last 3 years—I’ve not only lost whatever chance I might have had with commercial publishers, but have ostracized myself completely. I ain’t weeping about it—I‘m just seeing by my own lights. … I’ve sacrificed a good deal of my time with To, Objectivist Press, corresponding with 152 “poets” etc. to get up an issue of Poetry, an anthology etc., & the good things which resulted were their own cheque. However, I don’t care to do it again. I‘ve even stopped seeing “close friends” who’ve envied my station—to put an end to the bad taste of it all.64The Selected Letters of Louis Zukofsky, 120.

While Zukofsky’s interest in collaborative publishing efforts and the organization of writers to achieve the aims of literature in the United States did not die with the collapse of the Objectivist Press, his efforts to conduct this organization under the group name “Objectivists” did.65On January 22, 1935, the New Masses published a call to convene an American Writers’ Congress to address “all phases of a writer’s participation in the struggle against war, the preservation of civil liberties, and the destruction of fascist tendencies everywhere” (quoted in The Correspondence of William Carlos Williams and Louis Zukofsky, 215). The Congress, convened at New York City’s Mecca Temple from April 26-28, concluded with the establishment a League of American Writers and elected the novelist Waldo Frank to serve as its first chairman. Zukofsky invited both Williams and Pound to join him in supporting what he called an “united front of writers,” joining the League and participating in various of its activities over the next few years (quoted in The Correspondence of William Carlos Williams and Louis Zukofsky, 215). For more on Zukofsky’s involvement with the League of American Writers, see The Poem of a Life, 149, 169. Later in 1935, Zukofsky also appears to have relayed to Williams an invitation he had received to become a part of a group of “literary people of different countries” connected to Pound which would regularly exchange “technical, mostly prosodic, information, suggestions, etc,” which Williams was decidedly uninterested in (The Correspondence of William Carlos Williams and Louis Zukofsky, 218-219). While the Zukofskys did revive the Objectivist Press (in name at least) to publish Louis’ The Test of Poetry in 1948 and corresponded for a short time thereafter using The Objectivist Press letterhead with their home address as its current location, they did not use the imprint again for any subsequent publications and it appears that both Williams and Zukofsky considered the term defunct by the early 1950s, when Williams published his retrospective look at the group in his Autobiography.

RMR Press

In the early 1930s, Kenneth Rexroth planned to found a press with his friends Milton Merlin and Joseph Rabinowitch. As they conceived it, the RMR Press (the initial letters of their last names) would publish a series of pamphlets and short books, with a special emphasis on poetry. Zukofsky, Pound, and Williams all wrote to Rexroth in support of the venture, offering selections of their own work for consideration and providing extensive lists of authors they felt might be interested in being included in the series. Zukofsky named Reznikoff, Oppen, Bunting, René Taupin, Whittaker Chambers, George Crosby, and Harry Roskolenko; Pound recommended Rexroth approach Wyndham Lewis, Man Ray, Hilaire Hiler, Robert McAlmon, and Ford Madox Ford. Pound and Zukofsky discussed Rexroth and his proposed publishing venture in several letters from 1931 and 1933, with Zukofsky telling Pound in a letter:

Rexroth—if the business end of him still bothers you—said some months ago that he had got a “very friendly letter” from you and that only an extended vacation in the Calif. rockies was preventin’ him from answerin you. Also it seems he has been quarrelsome with his patrons. I hope his scheme does go thru—since he was wantin’ to get out my essays & poems.66Pound/Zukofsky, 107.

Carl Rakosi, in particular, appears to have believed that Rexroth would be shortly publishing a book of his poems, telling both Richard Johns and Harriet Monroe in the summer of 1931 that he was “planning to put out a book soon.”67Pagany letters from Rakosi, U Delaware, and Poetry papers U Chicago. In August 1931, Zukofsky told Morton Zabel that “the Rakosi volume to be published probably by RMR, Los Angeles — a new venture in printing books cheaply in brochure form, Rexroth is connected with the firm. You might write him and mention particulars he sends in Poetry. Of course, I should like to do [i.e. review the book for Poetry] the Rakosi, if it appears.”68Zabel Manuscripts, Special Collections, Indiana University. Unfortunately for Rakosi and others who may have had been making similar plans with Rexroth, the RMR Press never advanced beyond the planning stage, despite the several recommendations and clear expressions of interest by both Pound and Zukofsky.69For more background on RMR, see Linda Hamalian’s A Life of Kenneth Rexroth, pp. 65, 75-76.

Other 1930s Anthologies

In addition to the explicitly “Objectivist” publications already described, three other anthologies published between 1932 and 1934 included work by several of the writers who had appeared in “Objectivist” publications. Two of these were edited by Ezra Pound, and one by Parker Tyler, each of whom had appeared one of the Zukofsky’s “Objectivist” publications.

Profile

In May 1932, Ezra Pound published Profile, a 142-page anthology printed privately in Milan by John Schweiler in an edition of 250 copies. The anthology included a prefatory note from Pound describing it as “A collection of poems which have stuck in my memory and which may possibly define their epoch, or at least rectify current ideas of it in respect to at least one contour,” as well as a very short introduction, “Spectacle,” in which Pound wrote: “I am making no claim to present the ‘hundred best poems’ but merely a set of poems that have ut supra remained in my memory. I have tried to omit repetitions, whether by the same author or a different one.”70Profile, 10. The anthology itself offered a patchy historical narrative of the previous few decades in English-language poetry, beginning with Pound’s assertion that

This ‘anthology’ is merely the collection of poems that I happen to remember, that is, it is selected by a given chemical process. I don’t mean that I could quote these poems verbatim, but that they have had, each of them, during the last 30 years sufficient, individual character to stick in my head as entities.

The omission of certain writers before 1920 implies generally a direct censure or disapproval, that of writers since 1920 implies merely unfamiliarity or ignorance of their work.71Profile, 13.

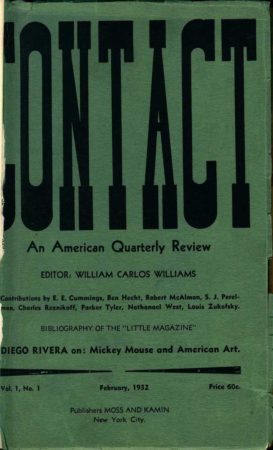

Of the “Objectivists,” Pound’s old friend Williams is the best represented in the anthology, with four poems in total: “Hic Jacet,” dated about 1910, “Postlude,” dated 1912, and “Portrait of a Woman in Bed,” published in 1917, as well as “The Botticellian Trees,” which Zukofsky had included in the “Objectivists” issue of Poetry. Pound also included work by six other writers Zukofsky had presented as “Objectivists” the year previously: McAlmon’s 1924 poem “The Bullfight”; the third, fourth and fifth “movements” of Zukofsky’s “Poem Beginning ‘The'”; Howard Weeks’ “Stunt Piece”; sections 1 and 2 of Bunting’s “Villon”; Emanuel Carnevali’s “The Girls in Italy” and “Italian Farmer”; and Parker Tyler’s “Experience Without Succedent.”

In the anthology’s editorial content, Pound was spare with his prose commentary, but reserved much of his praise for Williams and Zukofsky. For example, following a brisk summary of the appearance and impact of Des Imagistes he noted that “Out of several hundreds of American writers, Williams still continues to develop,” and described two tendencies in “the individualist American verse” over the previous dozen years, one of which, “only recently apparent or effective … perhaps showed first in Carlos Williams’ prose The Great American Novel and later in his poetry … [in which] a new sort of unity has been achieved, and that the parts are more definitely of the entirety than they had been in earlier sorts of poem which could be taken piecemeal or in quotation.”72Profile, 46, 127. Pound also indicated the overlap between his and Zukofsky’s editorial tastes via his provision of this list of “extant” writers: “Post war: Hemingway, McAlmon, Cummings. 1925 and after: Zukofsky, Dunning, Rakosi, Macleod, Bunting,”73113. particularly when one notes that of the five writers listed in the last group, only Ralph Cheever Dunning, an expatriate poet from Detroit who died in Paris from a combination of tuberculosis and starvation in 1930, was not included among Zukofsky’s “Objectivists.”

Reading Profile as “a critical narrative” in which Pound “attempted to show by excerpt what had occurred during the past quarter of a century,”74The prefatory “Note” included in his Active Anthology, 5. He described it in similar terms in Contempo, writing that the anthology was “a narrative of what has happened to verse during the past twenty-five years. the most ready conclusion to hand is that he considered Zukofsky’s “Objectivist” publications, alongside of his own magazine The Exile, as the source of the most significant developments in modern poetry since 1925. Pound made this approval explicit on the anthology’s final page by referring the reader in search of further information to “Zukofsky’s notes in ‘Symposium’ for Jan. and ‘Poetry’ for Feb. 1931” as well as the “Objectivist number of Poetry … and Mr. Zukofsky’s Objectivist Anthology, announced for publication.”75Profile, 142.

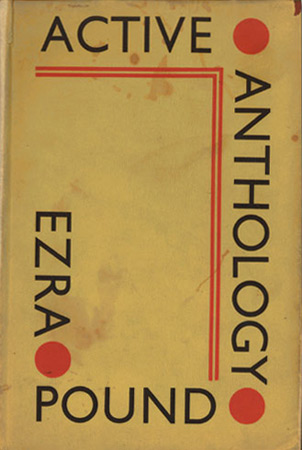

Active Anthology

The dust jacket cover of the Active Anthology, edited by Ezra Pound and published in 1933 by Faber & Faber.

On October 12, 1933, Ezra Pound published Active Anthology with the London-based publishing firm Faber & Faber, where T.S. Eliot served as a literary advisor. In an explanatory note preceding the table of contents, Pound noted that

My anthology Profile was a critical narrative, that is I attempted to show by excerpt what had occurred during the past quarter of a century. In this volume I am presenting an assortment of writers, mostly ill known in England, in whose verse a development appears or in some case we may say “still appears” to be taking place, in contradistinction to authors in whose work no such activity has occurred or seems likely to proceed any further.

In the volume’s preface Pound announced that he would be “confining [his] selection to poems Britain has not accepted and in the main that the British literary bureaucracy does NOT want to have printed in England” and claimed that:

the unwelcome and disparate authors whom I have gathered in this volume have mostly accepted certain criteria which duller wits have avoided. They have mostly, if not accepted, at any rate faced the demands, and considered the works, made and noted in my “How to Read”. That in itself is not a certificate of creative ability, but it does imply a freedom from certain forms of gross error and from certain kinds of bungling which will indubitably consign many other contemporary writings to the ash-bin. …

I have not attempted to represent all of the new poets, I am leaving the youngest, possibly some of the brightest, to someone else or to future effort, not so much from malice or objection to perfect justice, as from inability to do everything all at once.

There are probably fifty very bright poems that are not here assembled. … Someone more in touch with the younger Americans ought to issue an anthology or a special number of some periodical, selected with criteria, either his or mine.

The assertion implicit in this volume is that after ten or twenty years of serious effort you can consider a writer uninteresting, but the charges of flightiness or dilettantism are less likely to be valid.76”Praefatio,” 23-24.

Pound repeated many of these points in a brief “Notes on Particular Details” at the end of the anthology, writing

I do not in the least doubt that quite a number, say 20 or 30 poets between the ages of 20 and 40 have written better poems that some of those here included. But in a fair proportion of the cases where I have considered inviting an author and then refrained from doing so, I have very strong doubts as to that author’s capacity to progress or develop any further.

I expect or at least hope that the work of the included writers will interest me more in ten years’ time than it does now in 1933.77Active Anthology, 253

Pound’s list of eleven authors for the anthology included a strong “Objectivist” core; he included William Carlos Williams, Basil Bunting, Louis Zukofsky, and George Oppen among its contributors.78In addition to these four core “Objectivists,” Active Anthology also featured writing by Louis Aragon (translated by E. E. Cummings), E. E. Cummings, Ernest Hemingway, Marianne Moore, D. G. Bridson, T. S. Eliot, and Pound himself. Pound had assembled the anthology fairly quickly, sending Zukofsky a carbon copy of a call for submissions in late February. In the letter which accompanied it, Pound told the younger poet:

I take it this is a chance to print all of THE and all of A. that is ready /

also send suggestions/ re other of yrs/ the chewing gum poem, and items of interest.

//

also has Rakoski anything new/ or have you any snug gestionsOppen meritus causa?? couple of short poems??

lemme know if there are?Basil [Bunting] seems to think Reznikoff is some good??? any piece d’evidence?

Can you help ole Bill Walrnss [Williams] to sort hiz self out.79Pound/Zukofsky, 143.

Zukofsky complied, sending Pound work by Williams, Reznikoff, Rakosi, and Rexroth for consideration. Pound’s next letter to Zukofsky, sent in April 1933, expresses enthusiasm for Williams, Zukofsky and Oppen’s work

The Bill W[illia]ms/ is damn good. Shall prob. omit Footnote/ Ball Game / and Portrait of Lady ( the latter simply because the subject is less interestin’ than a lot of Bill’s other work.) I want another 15 Pages of him.

Your best stuuf is “The” and parts of A. …

Young Oppen has sent in stuff/ think three of ’em good enough to include.”80Pound/Zukofsky, 144

but lays out several reservations regarding Reznikoff, Rakosi and Rexroth:

The Reznikoff will appear to the Brit. reader a mere immitation [sic] of me, and they will howl that I am merely printin my followers.